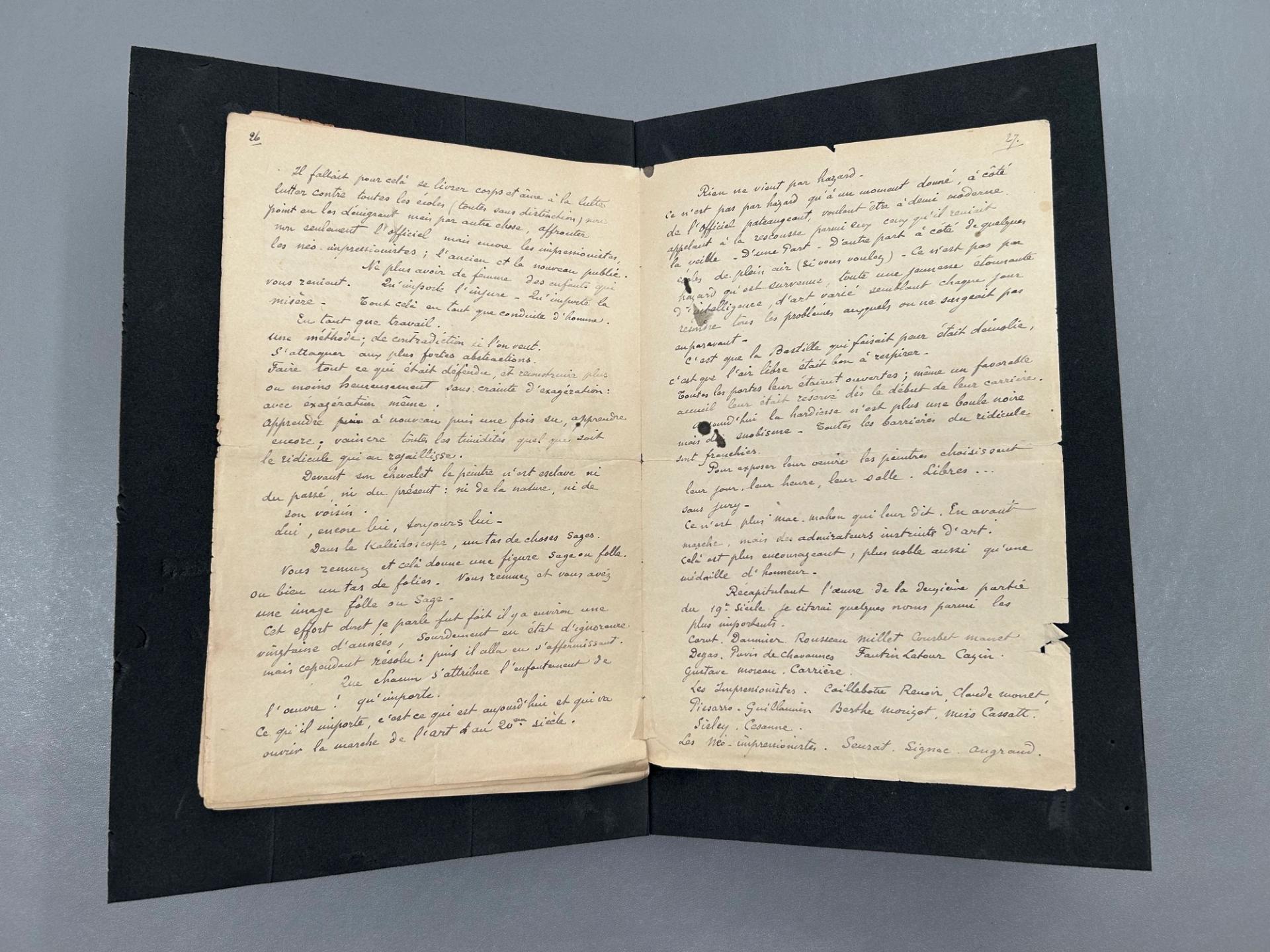

The Courtauld Gallery has bought the last literary manuscript by Paul Gauguin remaining in private hands. Written in 1902 on the remote Marquesan island of Hiva Oa in French Polynesia, it is bitter denunciation of critics who do not understand Modern art. It was submitted for publication in the radical journal Mercure de France, but rejected by its editors.

Gauguin entitled his French text Racontars de Rapin, which is difficult to translate. “Racontars” is probably best translated as Tales. “Rapin” is more complicated, since its traditional meaning was an apprentice or amateur artist. But in around 1900 it was also used differently, to describe a Bohemian or avant-garde artist. Gauguin, who enjoyed ambiguity, may well have intended his title to have a dual message. In writing about art was he posing as an innocent amateur or a knowledgeable avant-garde commentator? The Courtauld has just opted for Tales of an Apprentice Painter.

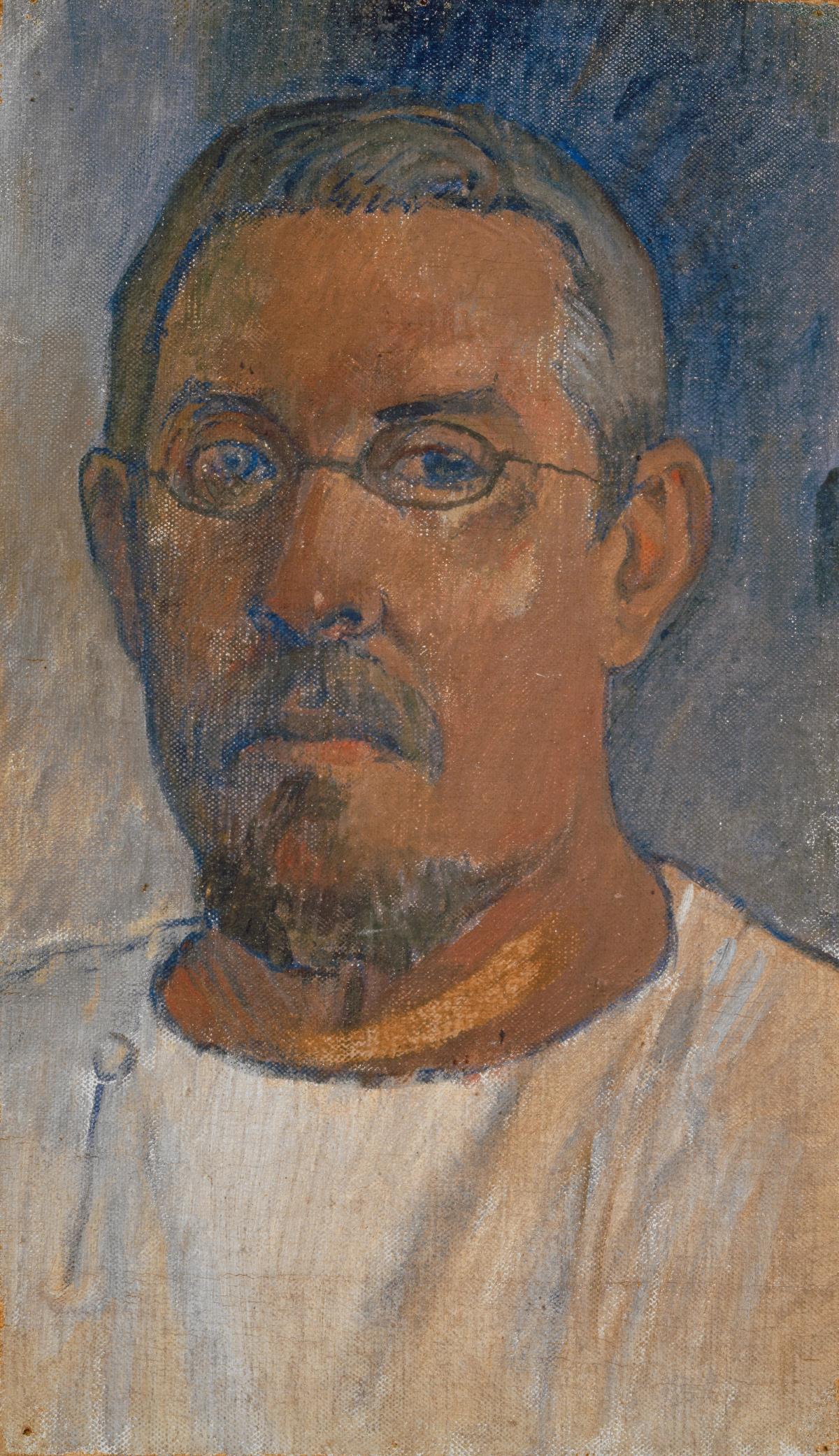

First and last pages of Gauguin’s Racontars de Rapin (Tales), September 1902

Photo: Christie's

The 28-page Tales manuscript was bought at Christie’s in Paris on 21 October, when it went for €65,520. The auctioneers describe the document as “a veritable manifesto for Modern art, artistic freedom and the independence of painters from the limits imposed by critics and academics”.

The manuscript arrived in London this week and was immediately shown to The Art Newspaper. It has survived remarkably well, although the paper is fragile and needs careful handling.

In Tales, Gauguin writes: “The artist has to look to the future, whereas the so-called educated critic is only educated about the past… the painter is a slave neither to the past nor to the present.”

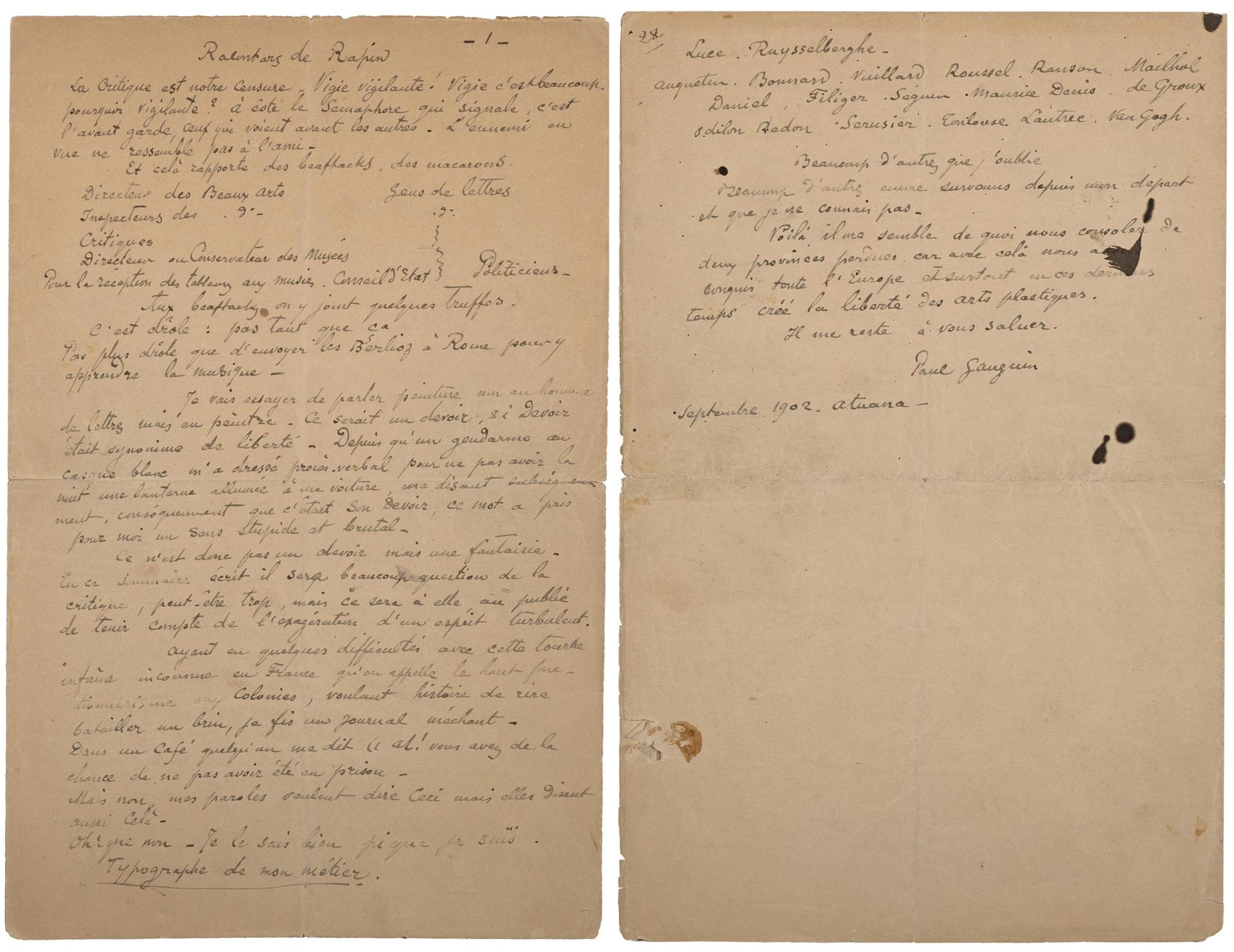

Gauguin's Racontars de Rapin

Photo: The Art Newspaper

Gauguin praises the Impressionists, who had arisen in the 1870s, saying they began as wolves, “since they had no collars”. He adds that they then went on to become an established group of painters, “with all the slavery it entails… it's one more dogma.”

When it came to naming individual artists, Gauguin praised Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who “draws well”. Camille Pissarro is “one of my masters” and much admired: “No matter how far away the haystack may be, over there on the hillside, Pissarro knows how to take the trouble to walk around it and examine it.” Gauguin even singled out the Pre-Raphaelite Edward Burne-Jones, “a sad Englishman, suffering from melancholia”, and the Anglo-American Whistler.

Forty other artists whom Gauguin admired are simply listed. They include Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Paul Signac, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Pierre Bonnard. Writing from his Pacific island home, far away from Paris, he added that there would also be “many others, arisen since I left, and whom I do not know.”

Towards the end of Tales Gauguin writes about an extraordinary occasion just after sunset, when he was sitting on a rock near his Marquesan hut, smoking. There suddenly appeared in the trees “a completely naked body, skinny, withered, completely covered in tattoos which made it look like a toad”. The figure who approached turned out to be a woman. She “examined me with her hand”, first on his face and eventually on his “virile member”.

The following day Gauguin was apparently told that the apparition was “a blind madwoman who was living in the bush, who ate the remains of swine”. For two months, the encounter remained “a haunting vision” for Gauguin, which he claimed impacted on his paintings: “Everything around me took on a barbaric, savage, ferocious aspect”. In Gauguin’s writings, it becomes difficult to distinguish fact from fantasy, dream from nightmare. His comments seem offensive today, although Gauguin regarded himself as a “savage”.

In September 1902 Gauguin sent Tales to André Fontainas, a Belgian Symbolist friend in Paris. In his covering letter, he asked Fontainas to send “this little manuscript, written in haste” to the Mercure de France: “What I have written has no literary pretensions, but it expressed a deep conviction which I am anxious to make known.”

Fontainas’ reply has been lost, but he reported back that the editors would not be publishing the manuscript. Tales may have been rejected by the Mercure de France because the journal frequently published art criticism, a form of writing so despised by Gauguin. The manuscript is sometimes obscure and difficult to follow, so it would have required considerable editing to make it suitable for publication. And readers might not have taken kindly to Gauguin’s account of his twilight encounter.

Gauguin responded to Fontainas in February 1903: “Your friendly letter does not surprise me as regards the Mercure’s refusal, I had an idea that this would happen.” Three months later Gauguin was dead, from a heart attack and possibly syphilis.

Fontainas kept the manuscript, perhaps until his death in 1948. It was later acquired by an unidentified American owner, who sold it in 1984. It was then bought by Sam Josefowitz, the distinguished Swiss collector of works by Gauguin and his circle in Brittany. The manuscript was then sold by his heirs last month.

Tales has ended up in an appropriate home, since in 2020 the Courtauld Gallery acquired another rare Gauguin manuscript, Avant et Après (Before and After). This was completed in February 1903, just five months after Tales. The Courtauld, which has three key paintings (The Haystacks, 1889; Te Rerioa, 1897 and Nevermore, 1897) is therefore set to become an important centre for research on the artist.

Ketty Gottardo, the Courtauld’s curator of drawings, says that this latest acquisition strengthens the gallery’s ability “to foster the study of this significant, and equally controversial, artist.” The institution also owns the artist's book-length manuscript Avant et Après (Before and After).

The Tales manuscript will be digitised for the Courtauld’s website early in the new year. For conservation reasons, it will only be possible to display it very occasionally, although it will hopefully be available for study by appointment in the print room. An English translation of the text was published in 2016 by David Zwirner Books, under the title Ramblings of a Wannabe Painter.