The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York has a transformative, grandiose new wing. While much attention in recent years was focused on the institution’s main eastern entryway facing Central Park, where debate raged over the fate of an offensive statue of Theodore Roosevelt—it was removed in early 2022—the institution has been planning and building the $465m, 230,000 sq. ft Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education and Innovation on its western, Columbus Avenue side for nearly a decade.

Working Collections in the Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. Collections Core at the American Museum of Natural History's new Gilder Center Alvaro Keding, © AMNH

The new complex, the Gilder Center for short, opened to the public earlier this month. It adds a dramatic new entryway and gathering place to the AMNH’s sprawling campus and goes some way to solving its tangled network of wings and corridors, connecting to half of the complex’s 20 buildings in 33 different places. It follows recent revamps of the museum's hall of gems and minerals, and its Northwest Coast Hall.

The Davis Family Butterfly Vivarium in the new Richard Gilder Center for

Science, Education and Innovation Alvaro Keding, © AMNH

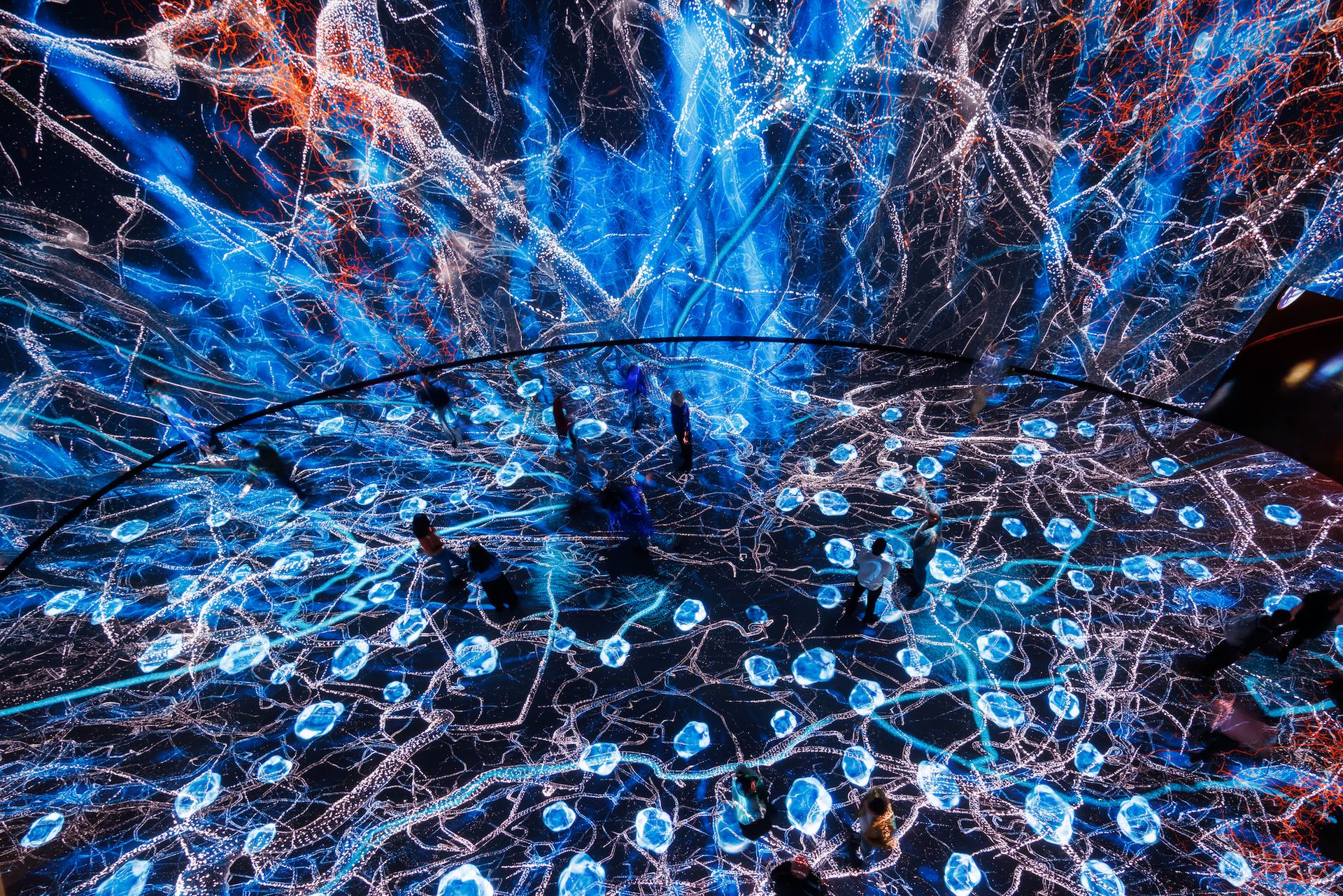

The centre houses new exhibition and display areas devoted to insects, a restaurant, visible storage, a library, classrooms, laboratories and more. It includes a butterfly vivarium, where visitors can walk among hundreds of live specimens as they flutter about in a lush tropical setting. Another permanent fixture is an immersive and interactive video experience called “Invisible Worlds” that focuses on miniature and microscopic natural processes like firing brain neurons, the exchange of nutrients and water between tree roots and the importance of plankton to ocean ecosystems.

The "Invisible Worlds" immersive experience at the Gilder Center Photo: Iwan Baan

For the museum’s longtime leader Ellen Futter—now president emerita after stepping down earlier this year and being succeeded by Sean M. Decatur—the Gilder Center serves a key function at a moment when science has become increasingly politicised. “The goals of this building were intensified and made all the more urgent by the pandemic and the emergence of a post-truth world,” Futter said at a press conference. “This building is an antidote to misinformation and science denial.”

Sightlines from Gilder Center's third-floor bridge Photo: Iwan Baan

The centre achieves this in part by instilling an irrepressible sense of awe and wonder at the natural world, which some of the museum’s older displays and classical spaces can’t quite conjure. Designed by Chicago-headquartered architecture firm Studio Gang (which also just completed a connective expansion of the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts), the Gilder Center looks sleek and unobtrusive enough from the outside—perhaps due in part to opposition from preservationists after the project was first announced in 2014.

The exterior of the American Museum of Natural History's new Gilder Center at dusk Photo: Iwan Baan

“We wanted the building to offer and open up an invitation, to bring new levels of visibility into the museum and be as visible and accessible as possible,” said Jeanne Gang, the founder and principal of Studio Gang. She described the centre as “an innie building” that invites visitors inward, rather than projecting outward. It was conceived “as if it had been carved from a solid block”.

The Gilder Center's Kenneth C. Griffin Exploration Atrium Photo: Iwan Baan

Stepping into its five-storey atrium, with its dramatic skylights and smoothly rounded concrete surfaces, transports visitors to the river-carved canyons in the desert Southwest, or perhaps underwater to a tropical coral reef. The soaring space boasts sweeping forms and dramatically suspended walkways. It is a stunning addition to both the AMNH campus and the public-facing architecture of New York City, neither of which have anything quite like it.