A recently discovered sketchbook by 16-year-old Catharina Kam includes a drawing of an elderly woman peeling potatoes, a subject tackled simultaneously by Van Gogh. Catharina along with her brothers Jan and Willem knew Vincent well, and together they used to go on sketching excursions in the Dutch countryside. It was almost certainly on one of these occasions that Catharina and Vincent both drew the woman.

Catharina’s drawing is reproduced for the first time in the Atlas Van Gogh in Brabant, by Helewise Berger and Ron Dirven, published yesterday (30 March), on Vincent’s birthday. It was launched at the Vincent van Gogh House in Zundert, the artist’s birthplace. The profusely illustrated book in Dutch provides details of 46 sites relating to Van Gogh’s life in Brabant, the province in the south of the Netherlands near the Belgian border where he was brought up and where his parents lived.

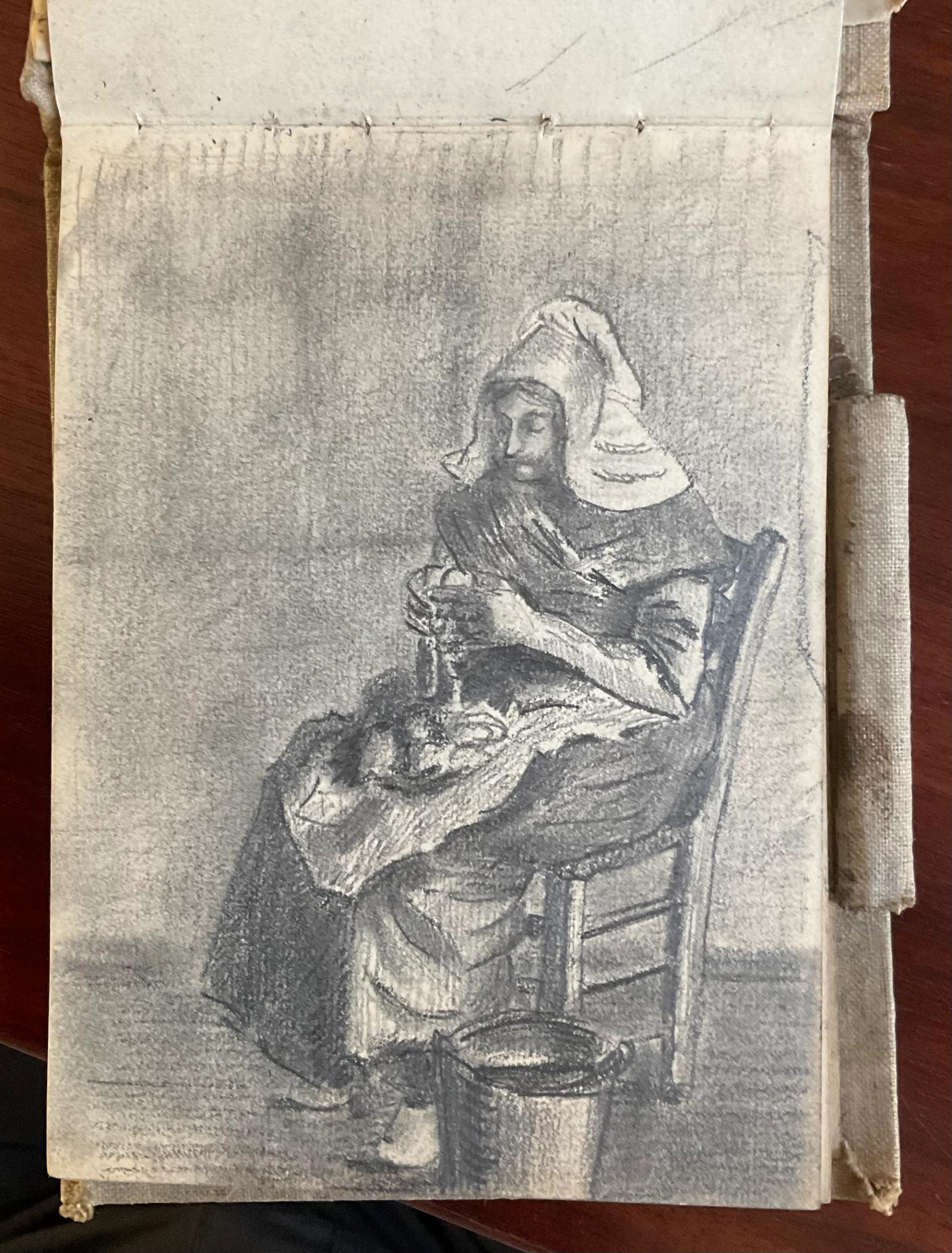

Catharina Cornelia Kam’s Woman peeling Potatoes (September 1881)

Credit: Private collection (Kam family)

Catharina (1865-1955) was the daughter of the Reverend Jan Gerrit Kam (1833-1917), the pastor in the village of Leur, which lies adjacent to Etten, where Vincent’s father Theodorus served in the same role. The two Protestant clergymen were colleagues and their children became friends.

Vincent, then 28, lived in Etten from April to December 1881. A year earlier, while he was an evangelist in the Belgian coal mining area of the Borinage, he realised that he was failing in his vocation - and he decided to set out to become an artist. But his early efforts at drawing were crude and he found it challenging.

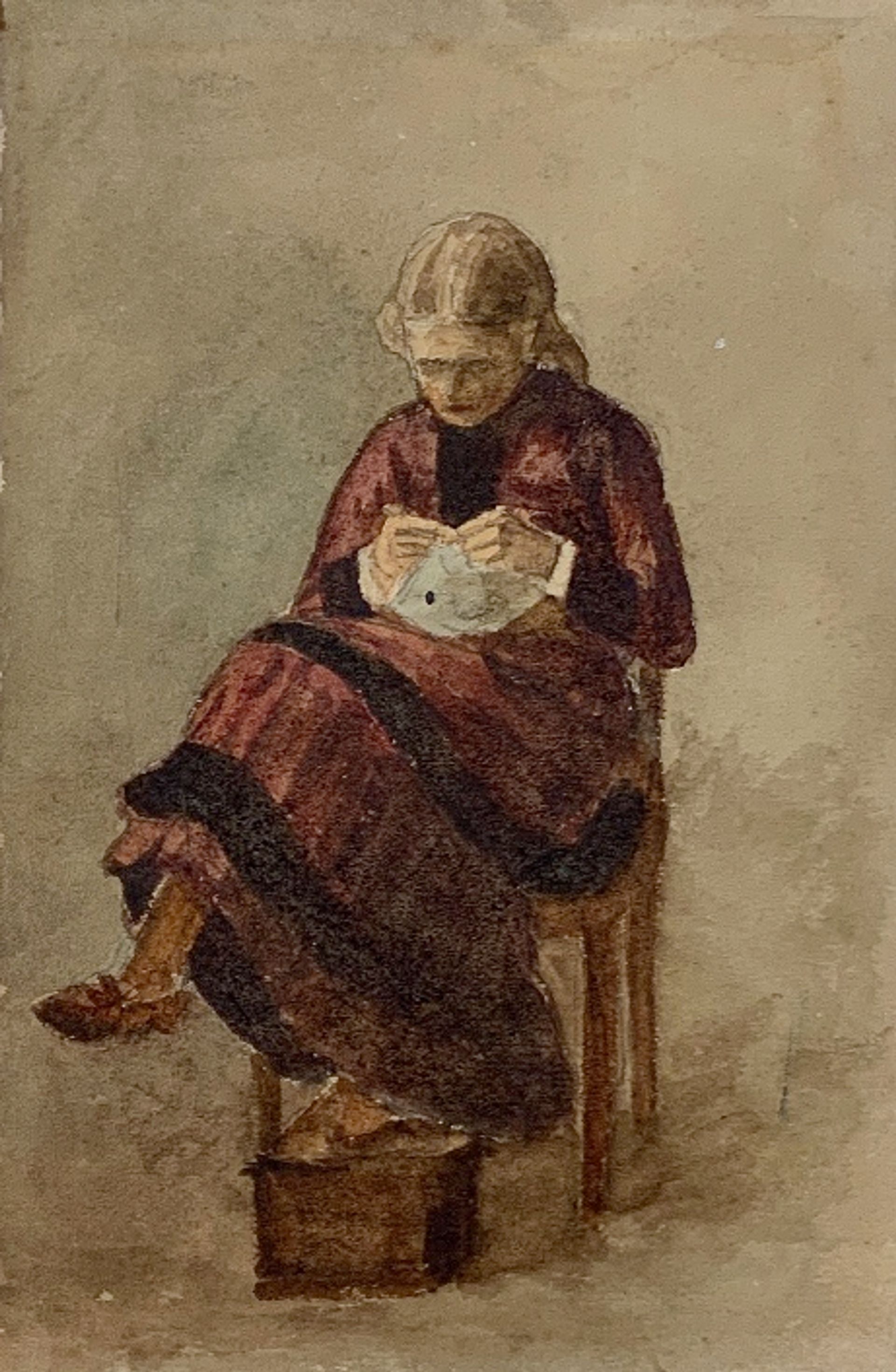

Van Gogh’s Woman peeling Potatoes (September 1881)

Credit: Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Catharina’s older brother Jan Benjamin (1860-1932) later recalled that in Etten-Leur Van Gogh would sketch the local peasants. In 1912 Jan wrote to the critic Albert Plasschaert: “He was drawing sowers then, and went into small dwellings to draw the woman doing some domestic chore.”

The sketches by Vincent and Catharina both depict the same woman in her cottage home, sitting and preparing potatoes beside a window. Although the compositions are very similar, the woman is depicted from slightly different angles, with Catherina apparently positioned while drawing just to the left of Vincent.

The different angles mean that one drawing is not simply a copy of the other, and they must both have been done from life. We can date the occasion, since Vincent wrote to his brother Theo in mid-September 1881 that he was drawing “a woman with a white cap who’s peeling potatoes”. Vincent also seems to have made another smaller sketch on the same occasion, but the one illustrated above with Catharina’s drawing seems to have been the more considered.

The identity of the woman, wearing a traditional white bonnet and wooden clogs, remains unknown. Van Gogh has included a view from her window, a row of pollarded willows, but this is probably an imaginary landscape typical of the area, and not what could actually be seen from inside her hut. Catharina only vaguely indicated the window, leaving greater emphasis on the figure.

The wooden bucket is in different positions in the two drawings, so either Vincent or Catharina may well have shifted it to improve their composition. Vincent added a little watercolour to his drawing, blue and red on the woman’s clothing and red to indicate the dark interior of the bucket. Catharina also included a white cloth or apron on the woman’s lap.

What is striking is that Van Gogh had great difficulty in handling the perspective of the chair: the lower crossbars at the front appear to be almost a continuation of the side ones, rather than being depicted at more of more of an angle. He has also made the woman’s upper leg far too long in relation to the rest of her body.

Catharina has captured the perspective and proportions more successfully, although both of them have made the head rather small. Her drawing also conveys more of the woman’s concentration on her task.

So in 1881 was the young Catharina a better artist?

Dirven points out that she was “well educated and mastered drawing techniques remarkably well”. Catharina was “more academically schooled, whilst Vincent focused more on expression, disliking an academic approach”. But from a technical point of view, she was clearly more advanced.

At the time Vincent admitted to his brother Theo that he had much to learn, although he was making progress. In the same letter about the potato peeler, he added: “What used to seem to me to be desperately impossible is now gradually becoming possible, thank God… Diggers, sowers, ploughers, men and women I must now draw constantly. Examine and draw everything that’s part of a peasant’s life.”

Van Gogh’s Woman peeling Potatoes (September-October 1881), a slightly later watercolour

Credit: Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

A month after the drawing session with Catharina, Vincent made a much more accomplished watercolour, setting the woman against a dark background. This time he avoided the perspectival problems of depicting the chair, by omitting the front crossbars (they are partially disguised by the woman’s dress). He also moved the bucket to the foreground, apparently following Catharina’s lead.

After his initial efforts in Etten, Van Gogh’s progress was swift. Within a few years, he had mastered perspective. He became so proficient that he would sometimes deliberately flout the laws of perspective, to achieve an effect. This can be seen in his evocative painting of The Bedroom (October 1888), completed just six years after his hesitant Etten drawings.

Van Gogh’s The Bedroom (October 1888)

Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

By complete coincidence, the only image that seems to have survived of Catharina at roughly the time she knew Van Gogh is a watercolour which shows her in a fairly similar pose to the elderly woman. Catharina rests one foot on a traditional box warmer. Depicted seated, from a similar angle, she too concentrates on a task - crocheting or lace-making, rather than peeling potatoes. It was painted by her brother Willem Hendrik (1863-1918), who went on to become an architect and draughtsman.

Willem Hendrik Kam’s watercolour of Catharina (probably 1880s)

Credit: private collection (Kam family)

Melitta Steenhuis, a great-granddaughter of the Reverend Kam, told me that his children were “brought up in an artistic family” and according to tradition often went out drawing with Van Gogh. Melitta herself is a sculptor and makes jewellery, suggesting that the Kam family has lost none of their talents.

The Atlas Van Gogh in Brabant is due to be published in English, hopefully later this year.

Cover of Atlas Van Gogh in Brabant by Helewise Berger and Ron Dirven, published by W Books

Courtesy of W Books, Zwolle