Heinrich Campendonk (1889-1957) was a member of Der Blaue Reiter (the Blue Rider) group of German Expressionist artists in the period before the First World War. Though represented in many eminent German and Dutch public collections, he is arguably the least known artist of that celebrated movement.

Gisela Geiger’s short, hardback monograph is a handsomely illustrated introduction to Campendonk. Giving a rounded picture of his life and work, Geiger—a curator and director of the Campendonk collection at Germany’s Penzberg Museum—includes a substantial chronology, illustrated with photographs, and a short final section of letters and documents illuminating the artist’s personal thoughts.

Like many of his generation, Campendonk’s career was upended by the political developments in Germany during the 1930s and 40s. Suspended and then sacked from his post at the Düsseldorf Academy, Campendonk emigrated to Holland and continued his teaching career in 1935 at the National Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam. Included by the National Socialists in the Entartete Kunst (degenerate art) exhibitions, he nonetheless declined to submit his work to the Modern German art exhibition mounted in London in 1938 as a riposte.

When The Netherlands was invaded by Germany, Campendonk—like other German artists such as Max Beckmann, who lived in Amsterdam from 1937—was placed in double jeopardy. He was threatened by officials from the regime he had escaped, but remained under suspicion by the occupied Dutch. He suffered a breakdown, not the first during his lifetime. He was compelled by the German occupying forces to do sentry duty, before going into hiding. Resisting offers to return to teaching posts in Germany after the war, he became a Dutch citizen and remained in Amsterdam.

Born in the Rhineland in western Germany, Campendonk’s decision to become an artist was opposed by his family, leading to a compromise that saw him training not as a “free” artist, but in the vocationally more secure applied arts. Throughout his career he frequently returned to applied arts in his practice. In his middle years, applied art commissions—in particular for multiple stained-glass windows in churches in Germany—dominated his career. His professorship in Düsseldorf (where he was appointed in 1926) was for murals, stained glass, mosaics and tapestry weaving.

With substantial artistic commissions and activity in these fields, it is regrettable to have only one black-and-white illustration in the biography section documenting him working on a window painting in Echternach, around 1930. The author and publisher’s focus on better-known paintings and works on paper from his early and later years is possibly the reason for the sudden leap in the final pages to paintings from 1922 to 1950.

Geiger introduces the applied arts thread in Campendonk’s career early on, with a tantalising mention—though not followed up with any further information or analysis—of a commission for a Russian church around 1911, passed on by Wassily Kandinsky. This was the moment of Campendonk’s broader artistic breakthrough, with the inclusion of several works in the seminal Der Blaue Reiter exhibition at Galerie Thannhauser in Munich in 1911. (The catalogue lists two works; Geiger mentions that three were shown.)

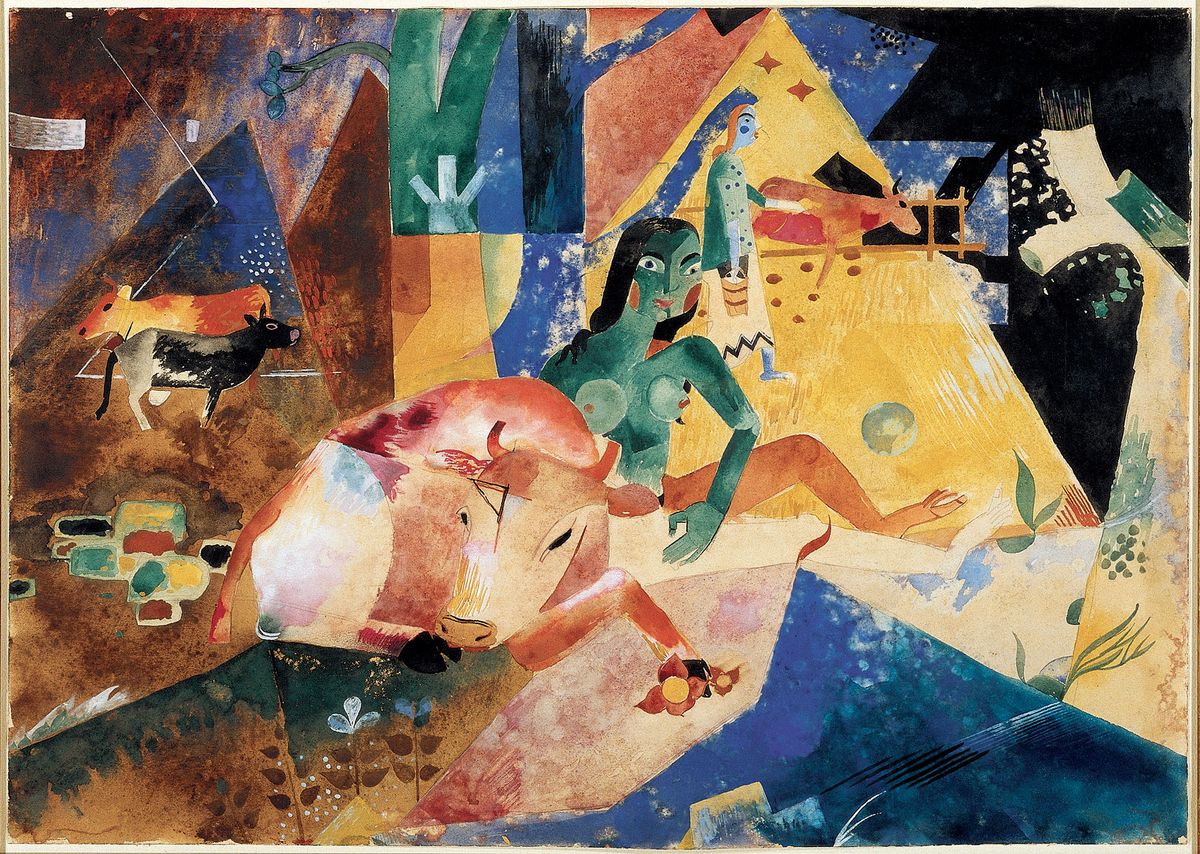

The artist was introduced to the group through August Macke’s cousin Helmuth, one of his student friends. After meeting Franz Marc in 1911, Campendonk moved from the Rhineland to Sindelsdorf in Upper Bavaria, living near to other artists of the movement. Geiger draws attention to the vivid colours in Campendonk’s work, at this stage absorbing the prismatic colour fields in Robert Delaunay’s paintings, as much as the sweeping lines giving direction and dynamism in the primordial natural visions of Franz Marc. Campendonk’s exposure to the artistic confluences through the Blaue Reiter exhibitions and his introduction to Herwarth Walden’s Galerie Der Sturm (where he encountered the spiky, psychologically intense graphic works of Oskar Kokoschka) enriched his practice.

Taking the Expressionist blueprint through the First World War, his works acquired an eyes-wide-open stillness, often combining farm animals and human figures, sometimes nude. Geiger describes these richly coloured paintings as possessing a ‘magical luminescence’. The Cow Shed (1920) and Girl with Cows (around 1919) exemplify this nocturnal suspension between imaginary scenes and observed rural activities. His paintings from this time, including intensely coloured interiors, relate to the heightened colours and anti-gravitational compositions of Marc Chagall.

Works from this period are the ones most likely to be found in most German public collections, and are the most sought after in the market. Campendonk’s international reputation is strongest in the sphere of graphic arts, with holdings in important American museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which held a solo exhibition in 1931. However, his works deserve to be more prominently on display and better known.

This publication, in English, adds to a list of 23 artists in this series already published by Hirmer, with an emphasis on German and Austrian artists alongside several very well-known figures, including Van Gogh and Picasso. With artists such as Gabriele Münter not (yet?) included, there is still some way to go to address the gender imbalance. Notwithstanding this, Geiger provides a fine introduction to Campendonk’s art.

Gisela Geiger, translated by Isabel Adey

Heinrich Campendonk (The Great Masters of Art series), Hirmer Verlag, 80pp, 37 colour and, 17 b&w illustrations, £9.95 (hb), published 26 January 2023

• Sean Rainbird is an independent curator and a non-executive board member. He was director of the National Gallery of Ireland (2012-22) and of the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart (2006-12), and between 1987 and 2006 he was curator and senior curator at the Tate