It is a surprise to find a study of Henry Moore (1898-1986) that does not illustrate a single “reclining woman”, or hardly any women at all apart from untypical groups of standing figures.

Chris Owen, the former head of the Cambridge School of Art, Anglia Ruskin University, gives a detailed account of Moore’s 1941-42 commission for the War Artists’ Advisory Committee (WAAC) to record coalminers underground in Yorkshire: a vital but unseen part of the war effort. He then brilliantly uses this to explore a revealing aspect of Moore’s over-weighty career, finding a melancholy and mildly left political strain, which culminated in his death-ridden “black drawings” of the 1970s.

Moore’s coalmining images immediately followed his drawings of Londoners sheltering from the Blitz, and have always been in their shadow. It was the art historian Herbert Read who had suggested the subject, and Moore himself who asked if he could work at the Wheldale colliery in Castleford, west Yorkshire, where his father had spent his own working life.

The problems of the commission were extreme: having to work in the dusty, dark and claustrophobic coal seams by the light of lamps, of drawing men rather than women, and of walking stooped, and then crawling, more than a mile from the lift cage to the coal face. And beyond these were the social anxieties, returning to his father’s colliery and negotiating the gulf of class that now separated him, at the age of 43, from his upbringing.

It would be interesting if anyone remembered how Moore’s speech had changed over this time. He was no longer local, having just moved to a rented house in Hertfordshire after his London studio had been bombed. There are some creepily embarrassing photographs of Moore below ground, set up by a photographer for Illustrated Magazine, as if drawing a miner working, but who was of course pretending.

And lastly there was the fascinating aesthetic issue. Moore had an unusual method of working, forming a mental picture of a new sculpture before drawing this figure complete, and then again and again from different points of view altered on the page. This was unlike the practice of his major predecessors like Aristide Maillol, who began with drawing a posed model, or Jacques Lipchitz, who started with his hands in a lump of clay. But in the mines Moore had to sketch straight away from life, facing a moving body, having before had no interest in people moving, or in conversation, or even relating to one another.

Nevertheless, Moore was tough and stuck out these problems to find new images, notably of a miner wielding a two-handed pick while lying half naked on his side, or bent over pushing a truck on rails. He also considered a few rhetorical subjects, but dropped them, of a miner standing holding a lamp and looking like Holman Hunt’s The Light of the World, or another like a Francis Bacon with a breathing mask and head torch.

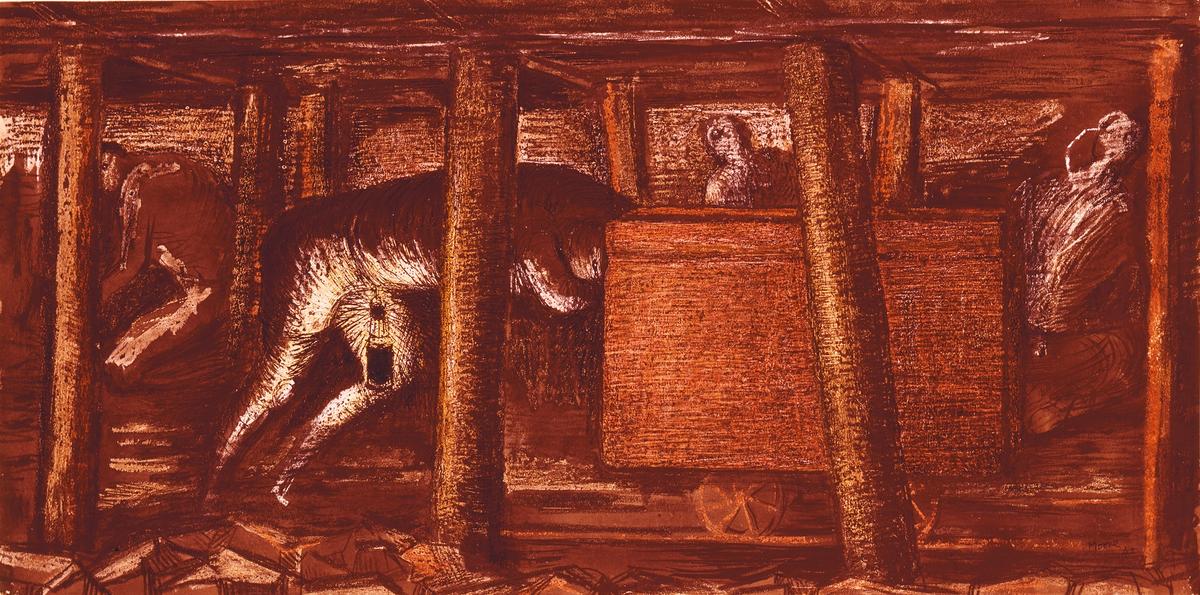

Moore completed 27 drawings, all of them from studies underground. They are totally original, of ghostly figures partly lit, muscular, with bodies twisted with the strain of attacking the rock around them. The WAAC, which was to pay him for work and all expenses, accepted these with enthusiasm. They were displayed in the National Gallery in 1942, empty of its Old Masters in wartime, a part of the changing official commissions. But they have not since, before now, been admired all that much, though some other drawings were bought in the US as well as by collectors in Britain.

Reverse of heroic

Owen points to their connection with Moore’s two 1950s full-length bronze sculptures of defeated warriors, in their resemblance of pose and in their representation of generic Man, taking him as the reverse of heroic, struggling and suffering defeat. It might seem arrogant that Moore never identified nor gave any personality to the people he always called “Miner”, but his purpose was not realist—rather, to find an overall image of the position of a working-class man.

Owen gives space to paintings by the miners of the Ashington Group (together from 1934) and to Oliver Kilbourn, who seem by contrast conventional and not necessarily more honest noters of what they saw, with their accessible John Berger kind of art, but with none of the suggestiveness of the intolerable condition of Man that was found by Moore. Owen considers whether Moore’s sculpture is weakened by belonging only to a separate cultural space, on a pedestal of reputation, and considers, I think, that that might be the case.

There is a discreet personal connection. Owen notes that his own father had been a Bevin Boy, sent to work in a colliery in Northamptonshire in 1944-47. Hence, perhaps, his sensitivity to the pervasive tensions of social class.

• Drawing in the Dark: Henry Moore’s Coalmining Commission, Chris Owen, Lund Humphries, 168pp, 140 colour and b/w illustrations, £40 (hb), published 2 November 2022

• David Fraser Jenkins was the senior curator of Modern British art at the Tate; author of Paul Nash: The Elements (Scala, 2010), which accompanied his exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery; and co-author of The Art of John Piper (Unicorn, 2016)