The Lebanese capital has been rocked by a series of escalating crises over the past four years, including the explosion of hundreds of tonnes of ammonium nitrate in its port on 4 August 2020, which killed hundreds of people, wounded thousands, and caused billions of dollars’ worth of damage. At the time, Lebanon was nearly one year into an economic crisis that the World Bank has ranked as one of the world’s ten worst since the 1850s.

The value of the Lebanese lira has now slumped by more than 90% since 2019. As a result, the government cannot buy enough fuel to keep the electricity on, and Beirut’s residents often have power for just one or two hours per day. Against this dark backdrop, a group of citizens and members of the Lebanese diaspora are working to give the city once known as the Paris of the Middle East its Centre Pompidou.

“We often get this very dumbfounded look when we say we’re building a museum in Lebanon amidst this crisis, with hungry mouths to feed, no gas and no electricity,” Taline Boladian, a co-director the Beirut Museum of Art (BeMA), said during a panel about the museum project held at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in November last year. “We need to preserve our national identity right now, precisely in this time of crisis, before it evaporates.”

Preparatory work at the future museum site began last February, and excavation for its multiple below-ground levels is due to start next month. Assuming that no archaeological vestiges are unearthed—hardly a safe assumption in a city whose occupants over the past five millennia have included the Ottomans, Greeks, Romans and Phoenicians—construction work will begin in earnest later this year. If all goes to plan, the building will be completed in 2026, more than 15 years after the project started to take shape.

BeMA began as a series of pop-up projects around Lebanon, with exhibitions and events in Tripoli and Washington, DC. But its raison d’être, as co-director Juliana Khalaf put it during the MoMA panel, is to display the Modern and contemporary Lebanese art that the government began assembling 100 years ago, and which has been stored precariously, deteriorating for more than two decades.

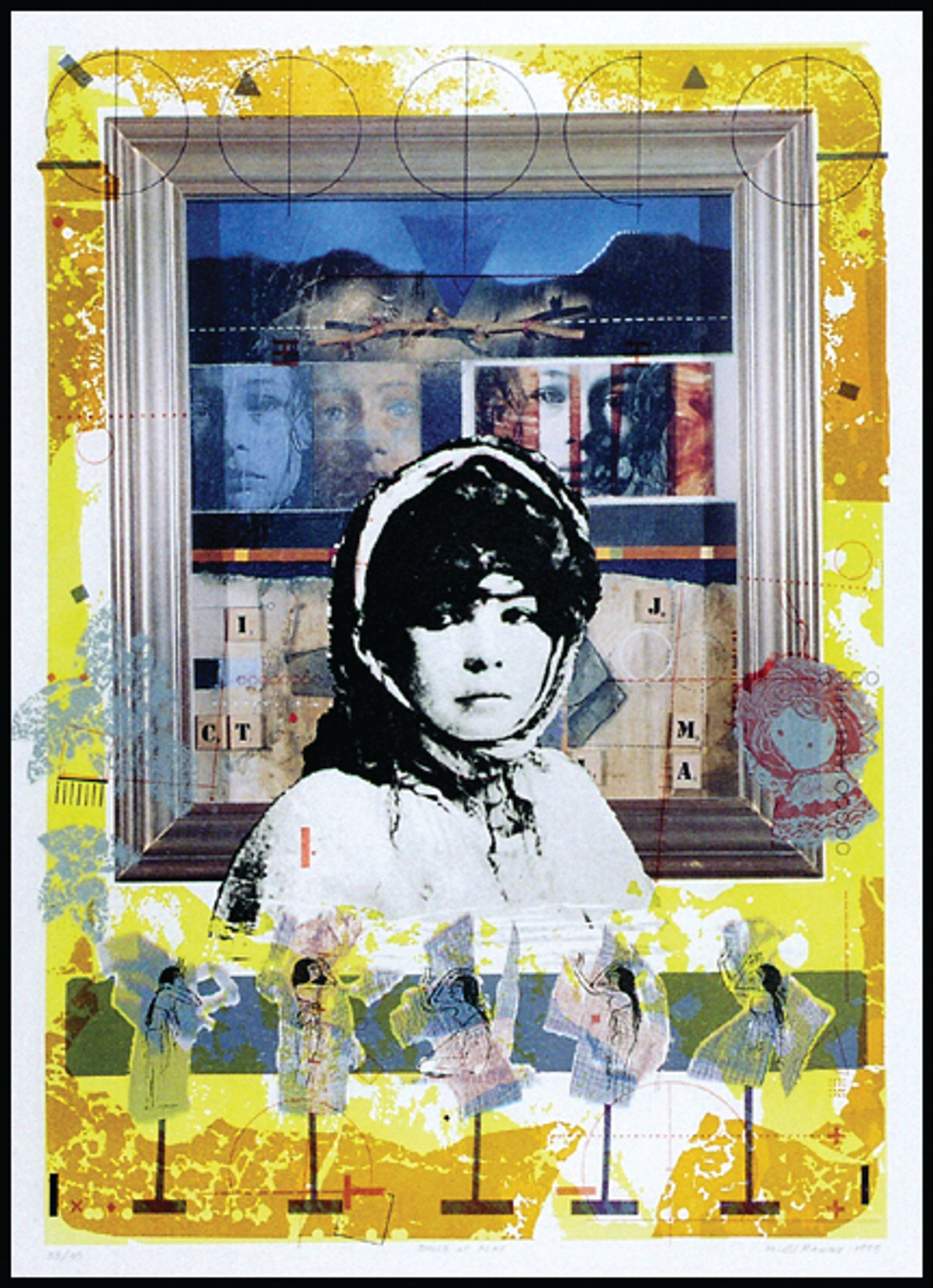

Mohamad El Rawas's Dolls at Play (1993)

Courtesy of The Beirut Museum of Art

Hidden collection

That art collection of around 2,500 works was begun by the Lebanese National Library after its founding in 1921. The Ministry of Education took over management of the collection in 1954 and continued to acquire works from the salons it organised, Beirut’s galleries and directly from artists’ studios. This practice continued even through the Lebanese Civil War (1975-90) until the Ministry of Culture took possession of the collection in 1993, storing it haphazardly in Beirut’s Unesco Palace. That is where Boladian and Khalaf found most of the collection (some pieces remain missing) in 2016, after BeMA signed an agreement with then culture minister Raymond Araiji to assess and catalogue the works.

“The state of the collection was atrocious when we first did the inventory,” Boladian said. “We were literally digging up paintings in bathrooms—albeit palace bathrooms—finding them in horrific condition. We had to offer the army guards fig-flavoured ice-cream to keep them from shortening our stay, or to help jog their memory for another room of undisclosed paintings.”

What eventually emerged, through an extensive cataloguing and conservation process that has restored almost 300 works from the government collection so far, is a unique chronicle of Lebanese modern art spanning the 1880s to 2001.

The new museum’s permanent collection will consist of 1,275 works by 210 artists drawn from the government collection. They include exceptional works from the French mandate era (1920-43) by artists influenced by the European avant-garde of the time, such as Moustafa Farroukh and Marie Hadad; works made after independence from France that reflect attempts to foster a national, naive aesthetic by Khalil Zgaib; and pieces showing the influence of American Abstract Expressionism by Helen Khal, Amine el Bacha and others. It also includes responses to and depictions of the brutality of the civil war, in works by Hassan Jouni, Mahmoud Zein el Din and their contemporaries.

As Boladian put it: “Nowhere else do you have a complete rendering of Lebanese art through which the history of the land and the people can be told.”