“If art belongs to the people, then it ought to get out of the musty-dank-but-spotless museums and spend some time with people.” A newspaper clipping of this quote by Linda Goode Bryant, who founded Just Above Midtown (JAM) in 1973, opens the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) sprawling exhibition charting the history of the influential gallery.

The survey brings deserved attention to the artists of JAM and to its founder. But Goode Bryant’s quote also highlights a paradox at the heart of such a show—that artists today still rely on the same “musty-dank-but-spotless museums” that controlled access, funding and space at the time of JAM’s founding.

JAM was a key launchpad and support for trailblazing artists of colour, particularly Black artists

The phenomenal quality of the art on view is unsurprising; JAM was a key launchpad and support for trailblazing artists of colour, particularly Black artists. Solo and group exhibitions, invitations to collaborate, special programmes and gathering space gave artists an opportunity to deepen their own practices and strengthen bonds among one another, reinforcing JAM as more than just another gallery.

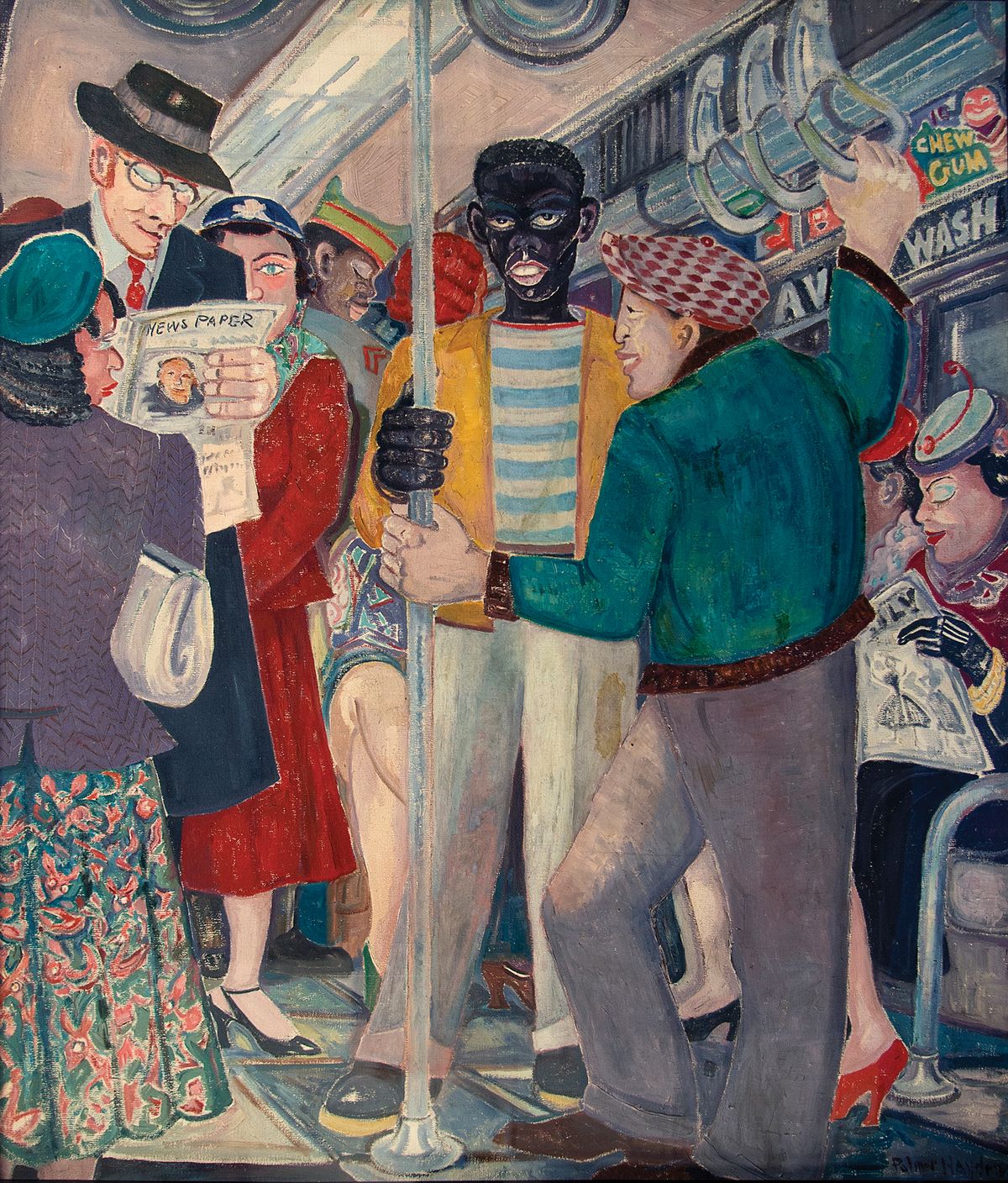

The exhibition covers the breadth of mediums that Just Above Midtown gallery showed, from textiles and painting to performance and assemblage, and includes work by now-famous artists such as Howardena Pindell, Senga Nengudi and David Hammons Photo: Emile Askey, © 2022 MoMA

The exhibition follows JAM’s chronology, beginning with its time at 50 West 57th St (until 1979), and illustrating its early embrace of material experimentation. From the get-go, printmaking, textiles, photography, assemblage, performance and painting could be found at JAM. In 1974, Goode Bryant suggested the gallery’s acronym “articulated its multiplicity”: JAM could mean “to block”, “an informal session among musicians” or “a food made by boiling fruit and sugar”. Like her suggestions, the gallery ethos recognised its divergence from the art industry, embraced collectivism and improvisation, and, of course, provided the space and time needed to create something sweet and delicious.

When other institutions would not give these artists a chance, JAM was their stage

Hanging hosiery by Senga Nengudi appears several times in the exhibition. While Nengudi’s name has ascended in the last decade—her work is on view elsewhere in MoMA, alongside that of fellow JAM artists Howardena Pindell, Suzanne Jackson and Maren Hassinger—contextualising this work and its origins provides a narrative arc of Goode Bryant’s influence. When other institutions would not give these artists a chance, JAM was their stage.

Wall labels throughout the exhibition specify how and when each work appeared at JAM, giving a potted history of the many characters who graced its space. One learns that Nengudi had two solo exhibitions and was featured in four group exhibitions at JAM. Very rarely did artists within JAM’s fold only encounter it once; they often returned, investing in the growth of the gallery and clearly trusting in Goode Bryant’s wider vision.

Jorge Luis Rodriguez’s Circulo con cuatro esquinas (Circle With Four Corners) (1978/2022), a large circular steel frame, leans in one corner of the exhibition next to a wall screening archival footage. The projection shows the artists Randy Williams, Noah Jemison and David Hammons dressing the collector Marquita Pool-Eckert in materials found in the gallery, as Goode Bryant comments from behind the camera. Then the film cuts again and Pool-Eckert, dressed in her spontaneous costume, sits inside Rodriguez’s circular work. Suddenly, the large sculpture, hollow and still, is awoken. No longer a circle, it becomes a portal, a spotlight, a frame for the work of JAM artists in communication with one another and with members of the art ecosystem: the gallerist and the collector.

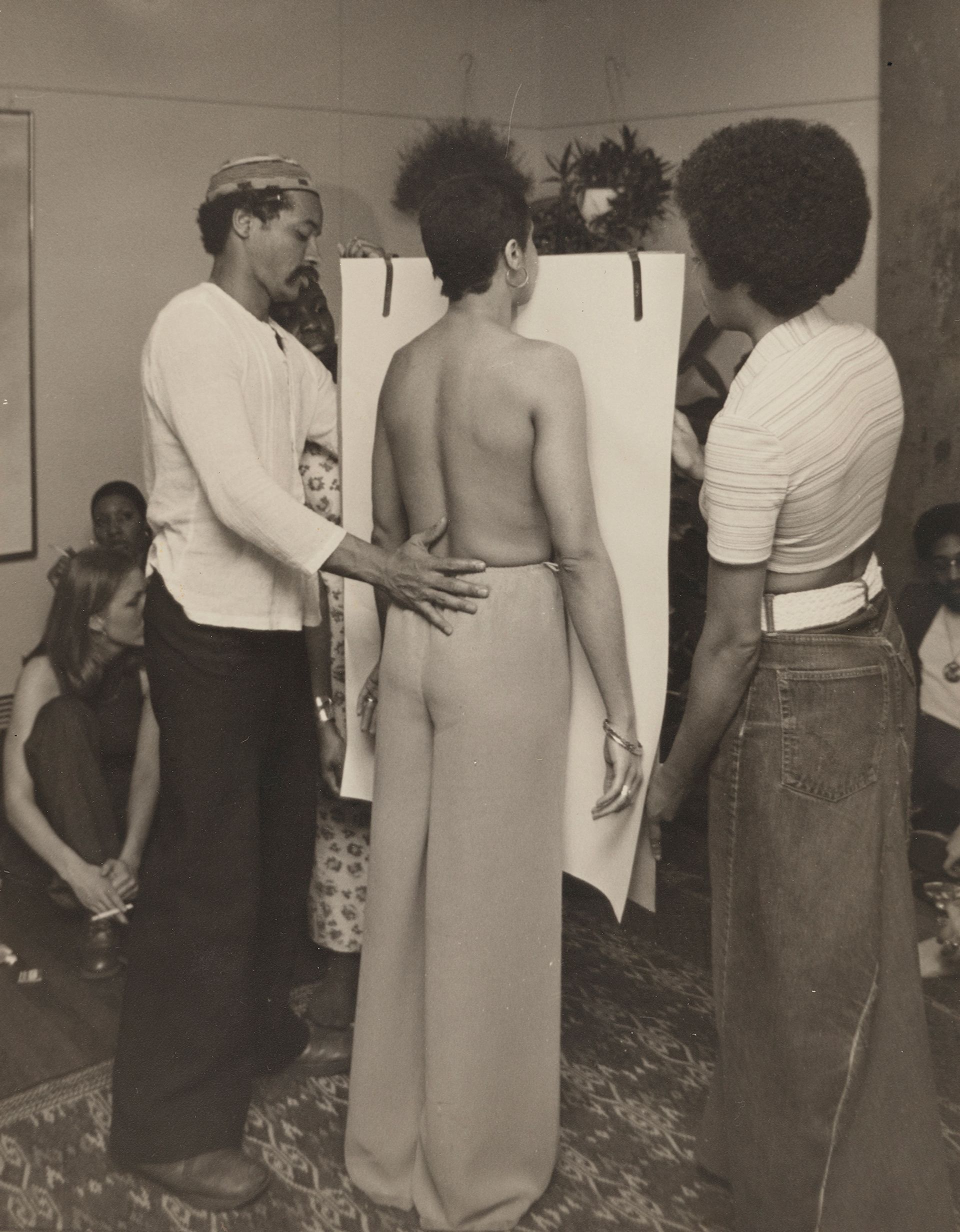

David Hammons (left) and Suzette Wright (centre) at the Body Print-In held in conjunction with Hammons’s exhibition Greasy Bags and Barbeque Bones; Philip Yenawine’s home, 1975. Photo: Jeff Morgan; Courtesy of David Hammons; Collection Linda Goode Bryant, New York

Photographs convey the lifeblood of JAM, standing for the many performances hosted by the gallery and recording the artist-run childcare provided for Goode Bryant’s two young children. But in the flurry of activity, a question arises: how did she do it? A hallway papered with overdue bills, pleas for payment extensions, or minimum payment invoices tells this side of the story. This archival material reinforces the humanness of JAM, demonstrating that its endurance required immense dedication.

The spirit of joyful experimentation seems to never recede

However, the spirit of joyful experimentation seems to never recede as the gallery progresses and relocates, first to Franklin Street in the early 1980s and then to its final home, from 1984 to 1986, at 503 Broadway. Notably, the gallery’s transposition from the commercial gallery district to the location of the more experimental art scene contributed to its embrace of mediums and subjects neglected by conventional art institutions.

Nina Kuo’s Contrapted Series Chinatown and Contrapted Series Quilt, Brooklyn (both 1983), overlay photographs of the titular New York neighbourhoods with colourful fragments, demonstrating how cultural memory is made from scattered debris. Rolando Briseño’s painting of a table on a tablecloth, American Table (1994), hangs above Tom Finkelpearl’s Wood mantelpiece with NYC MTA subway handles (early 1980s) and near a chair and lamp sculptures by Camille Billops, forming a surreal public-private domestic space of Chicano, Jewish and Black life.

JAM closed in 1986 after having to move out of its space for legal reasons. It continued briefly with a performance programme before Goode Bryant eventually turned her attention elsewhere, including making documentary films. Goode Bryant’s gallery showed that the creation and propagation of art holds not only a potential for activism—in the form of protest art or though the depiction of social movements—but also for radical organising. And it is through organisation, the setting of a vision and systematic working towards that vision, that change might occur.

In the final room of the exhibition, alongside David Hammons’s Flying Carpet (1990) is a new film a Negro, a Lim-o by Garrett Bradley and Arthur Jafa, commissioned for the show and produced by Goode Bryant, a reflection on the endless possibilities of artistic expansion. The pieces are positioned between galleries of the museum’s permanent collection, reminding viewers that the spirit of JAM might be hidden anywhere. It just requires a little curiosity to find.

• Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces is curated by Thomas Jean Lax and Lilia Rocio Taboada, and is at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 18 February 2023

What the other critics said about the exhibition

In his Artnews review, the senior editor Alex Greenberger lauds the exhibition for presenting JAM as its own art world and art history: “It’s less a play-by-play recap of the gallery’s 150 exhibitions than it is a show about JAM’s essence, which is reconstructed mainly by way of a tightly hung arrangement of artworks by artists who showed there.”

In the New York Times, Holland Cotter describes it as an “exhilarating exhibition”, praising Goode Bryant’s engagement with culture, her refusal of “white art world” expectations, and her spirit of generosity. As a result, he describes the MoMA presentation as “treasurable and utopian”.

In her review for Artsy, Ayanna Dozier recounts asking Goode Bryant at the exhibition’s press preview, “Can JAM still be JAM at MoMA?” Her thoughtful piece contains candid wisdom from JAM’s founder—including how she got rent down from $1,000 to $300—and aptly acknowledges the tension between JAM’s rebellion and MoMA’s officialdom: “While some may fear that MoMA’s resources may sanitise JAM’s mission statement, there’s enough thoughtful curation to dispel worries”.

In the Amsterdam News, Jordannah Elizabeth praises the exhibition as “a culturally profound celebration”. She states that the presentation of this history at MoMA “offers an opportunity to engage the next generation of Black artists”, inviting them “to explore their history and understand the strides that have been made for the Black community”.

• Just Above Midtown: Changing Spaces, Museum of Modern Art, New York, until 18 February 2023