Far from being a sensation, as its title declared, I thought the 1997 show of Charles Saatchi’s collection at the Royal Academy of Arts might be a bit of a damp squib. Many of the Young British Artists (YBAs) had already been shown at the Saatchi Gallery on Boundary Road or been given conspicuous solo exhibitions of their own: Damien Hirst and the Chapman Brothers at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) and Tracey Emin at the South London Gallery. Furthermore, Rachel Whiteread and Hirst had already won the Turner Prize. So surely it would just seem like a retread?

How wrong I was. First off, I hadn’t reckoned on the promotional genius of Saatchi and his ability both to surf and whip up the zeitgeist. It was an emotionally charged year, with Tony Blair winning a landslide election to become prime minister, Princess Diana meeting her untimely end, and Vanity Fair running its famous Cool Britannia cover. So, if London was swinging again, why shouldn’t its young artists storm the establishment? And what better place than the stuffy, venerable Royal Academy of Arts (RA)? The exhibition was a last minute stop gap when a hole appeared in the RA’s schedule and in the couple of months before the show’s September opening, Saatchi’s PR machine went into overdrive with flurries of press releases whipping up the anticipation with tantalising hints of scandalous works and promises of outrage to come.

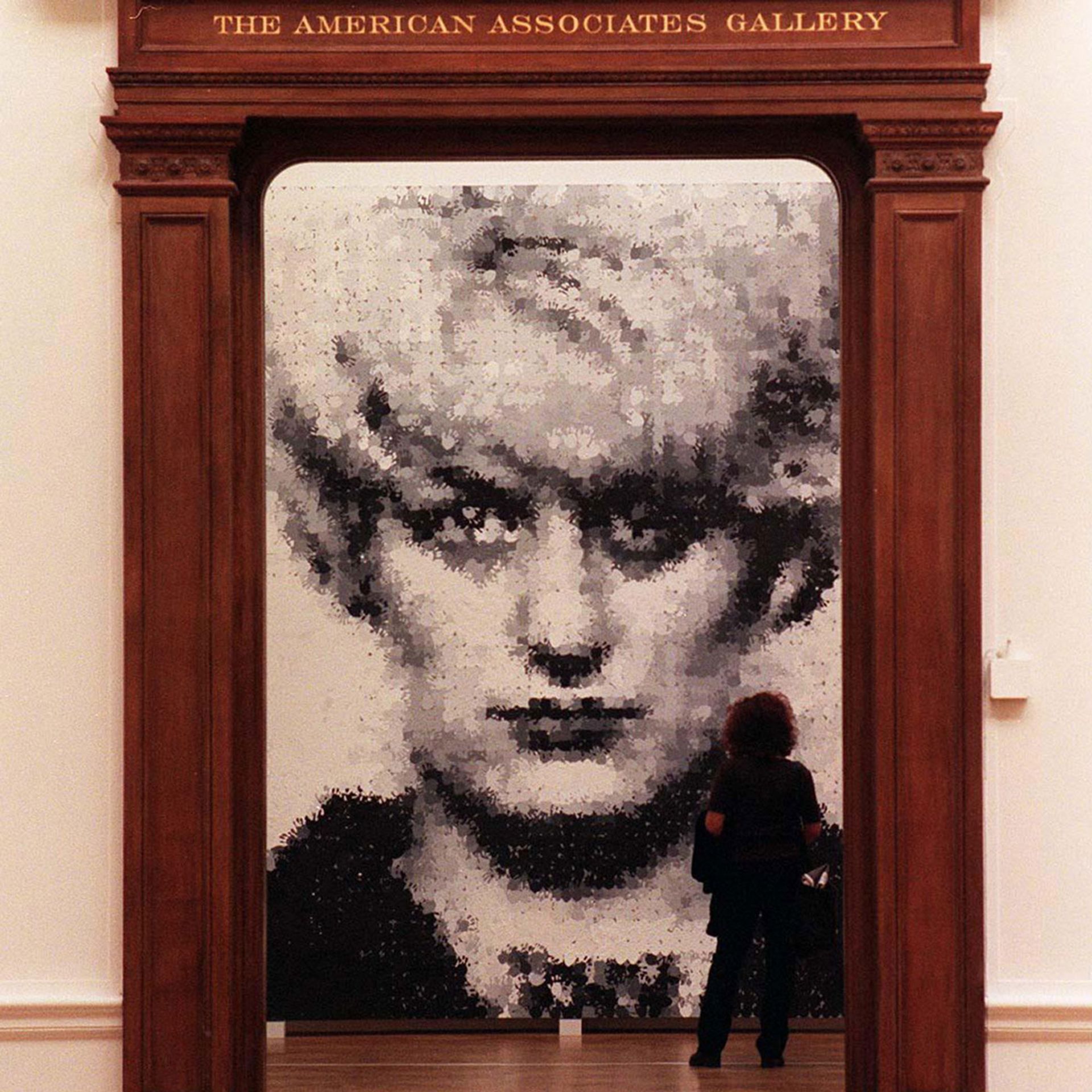

And come it did. Not with Hirst’s shark, Marc Quinn’s head made of frozen blood or the Chapman’s genitally misplaced mannequins, but with Marcus Harvey’s Myra (1995), a portrait composed of hundreds of children’s handprints and based on a police mug shot of Myra Hindley, who was imprisoned for life for the murder of five children in 1966. News of the work’s inclusion was leaked before the opening and once installed, Myra’s glowering presence caused an unprecedented public outcry, was vandalised by protesters, and vilified in the popular press. More controversy swirled around Emin’s tent bearing the appliqué names of everyone she had ever slept with. This was seized upon by the media as an example of her perceived sexual promiscuity, despite including relatives, junior school friends and an in-utero twin brother.

Marcus Harvey, Myra, on show at Sensation, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1997 © Marcus Harvey. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2022. Installation photograph: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo

The sound and fury whipped up around Sensation may have been problematic for the artists in the eye of the storm and drowned out more nuanced readings of what was on show, but the attendant hullabaloo swelled visitor numbers to more than 350,000 during the exhibition’s three-month run. For Saatchi it was win-win: the showing of his controversial holdings in the august setting of the RA raised both his and their profiles, validating both collector and artists as forces to be taken seriously. Such a conspicuous endorsement would be of financial benefit when Saatchi came to sell off many of the works in Sensation once the show finished its international run.

But from the outset Sensation was not all it might have seemed. The impression it gave was that Saatchi was the ultimate custodian of young British art and that he had owned all these artists right from the start. Yet while Saatchi had undoubtedly built the YBA brand—he used the term as the title for a series of shows in his gallery—a number of the key YBA works in Sensation had been hastily acquired in the run up to the show. Most notably among these works was Emin’s tent and Mat Collishaw’s Bullet Hole (1988), which was the centrepiece of the first Freeze exhibition of Goldsmiths students curated by Hirst in 1988.

All the mythology surrounding Sensation has also tended to obscure the fact that many of its 42 artists had little in common with each other or the core YBA crew. The non-YBA works ranged from Langlands & Bell’s architectural models and Yinka Shonibare’s mannequins clad in Dutch wax fabric, to Mark Wallinger’s huge oil paintings of racehorses, the quiet abstract canvases of Mark Francis, and Glenn Brown’s meticulous photorealist re-paintings of works by Frank Auerbach and Salvador Dalí.

Despite the way it raised their profiles, many of the artists in Sensation—and this included some of the most conspicuous YBAs—were not overly thrilled by their inclusion in the high-octane exhibition, which is now widely vaunted as their ‘coming of age’. Gavin Turk’s sculpture Pop—a life-sized self-portrait waxwork as Sid Vicious in the cowboy stance of Elvis as portrayed by Andy Warhol—was one of Sensation’s key exhibits. But when the artist attended the glitzy star-studded private view he went disguised as a bearded vagrant, dressed in filthy stinking rags with his feet wrapped in newspaper. “As an artist I felt as if I was being exposed in quite a large way but I wasn’t really involved,” he later told me. “The art was being used to the wrong end and actually it was somebody else’s party.”

Looking back a quarter century later, in many respects Sensation was undoubtedly a landmark show. It brought together an extraordinary number of great and art-historically important works, even if they often suffered at the hands of the overly spectacular and somewhat clunky narrative style of curating used by Saatchi and the RA’s exhibitions secretary Norman Rosenthal. It also channelled the bombastic, defiant spirt of the mid-90s and marked a ramping-up of the often unholy alliances between public spaces, collectors and commercial interests. Moreover, it proved the demonstrable power of mass communication and PR in making contemporary art exhibitions into must-see, big box office events. Turk was right, Sensation wasn’t really about the artists and their art, it was somebody else’s party—and its physically absent but omnipresent host was Charles Saatchi.

• Read a selection of our articles on the Sensation exhibition and its impact here