The fantasy of Egypt—its golden Pharaohs, hidden treasures and unsolved mysteries—continues to fascinate us, more than 2,000 years after the fall of the Ancient Egyptian civilisation. But how much of this gilded, mystical history is true—and how much is a modern-day construction?

A new exhibition, Visions of Ancient Egypt, opening 3 September at the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich, England, tackles this question on the eve of the anniversaries of the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphics (27 September 1822) and the discovery of Tutankhamun’s bountiful tomb (4 November 1922).

“A mirage is a good way to describe what we are trying to grapple with in this show,” says Theo Weiss, an assistant curator at the University of East Anglia’s museum. “We are pulling apart what we think we know about Egypt, and trying to understand how that idea came about in the first place.”

A Western colonial mindset is behind our modern and popular impressions of Ancient Egyptian culture, Weiss says. “Historically, Egypt has often been used for very deliberate political purposes,” he says. “Western powers have attempted to create a vision of Egypt that is used to further their own political agendas. That’s true for the Napoleonic Wars, or Augustus and the Romans, or the British Empire—and up until the modern day.”

The show can therefore be seen as a decolonial gesture. It is, in fact, listed in the Sainsbury Centre’s 2021 “Decolonisation Activity” paper where it is described as “[exploring] the enduring influence of ancient Egypt, through the lens of decolonisation and alternate histories”. The document outlines the ways in which the museum is working towards “the decolonisation of the gallery space” such as “revealing the colonial histories and provenance of objects with an emphasis on transparency” and engaging with more inclusive audiences.

Visions of Ancient Egypt takes a broadly chronological approach to displaying the more than 200 works on show. The majority of the Sainsbury Centre’s small collection of Ancient Egyptian items will be on view, including its “shawabti”—figurines used in Ancient Egyptian funerary practices. But most of the items are on loan from across the UK, Europe and Middle East.

A Canopic Jar by Josiah Wedgwood & Sons (1790) Courtesy of the V&A

A few large-scale pieces are being lent by the British Museum, including a marble bust of Jupiter Serapis (1st-2nd century AD), a god of fertility from Ancient Egyptian tradition that made his way into Greek and Roman culture. An alabaster canopic jar—used to hold the disinterred organs of mummified bodies—decorated with the Ancient Egyptian god of the afterlife, Osiris, is coming from the Dutch Royal Collection. It will be shown alongside a jar made in 1790 by the English porcelain and luxury accessories manufacturer Wedgwood, on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which copied the canopic design to create an everyday item for use in British homes.

The familiar characters of Ancient Egypt feature in the show. The opening section looks at how Cleopatra has been reinterpreted throughout history, from the wise scholar of Medieval Arabic literature to the glamorous siren played by Elizabeth Taylor in the 1963 film. The show will also include Joshua Reynolds’s 18th-century depiction of a socialite dressed as Cleopatra and Chris Ofili’s painting Cleopatra (1992), which presents her as a Black queen.

Two visions of Cleopatra: Joshua Reynolds's Kitty Fisher as Cleopatra Dissolving the Pearl (1759, left) and Chris Ofili's Cleopatra (1992, right). Reynolds: © Historic England Archive; Ofili: © Royal College of Art

A further section takes on the monumental legacy of Tutankhamun, the teenage Pharaoh who reigned from 1332 to 1323 BC. It will include archival photographs of the discovery of the tomb, which sparked international “Tutmania”. The images are shown alongside objects that demonstrate how the discovery of the tomb influenced the design of clothing, jewellery and furniture in the 1920s.

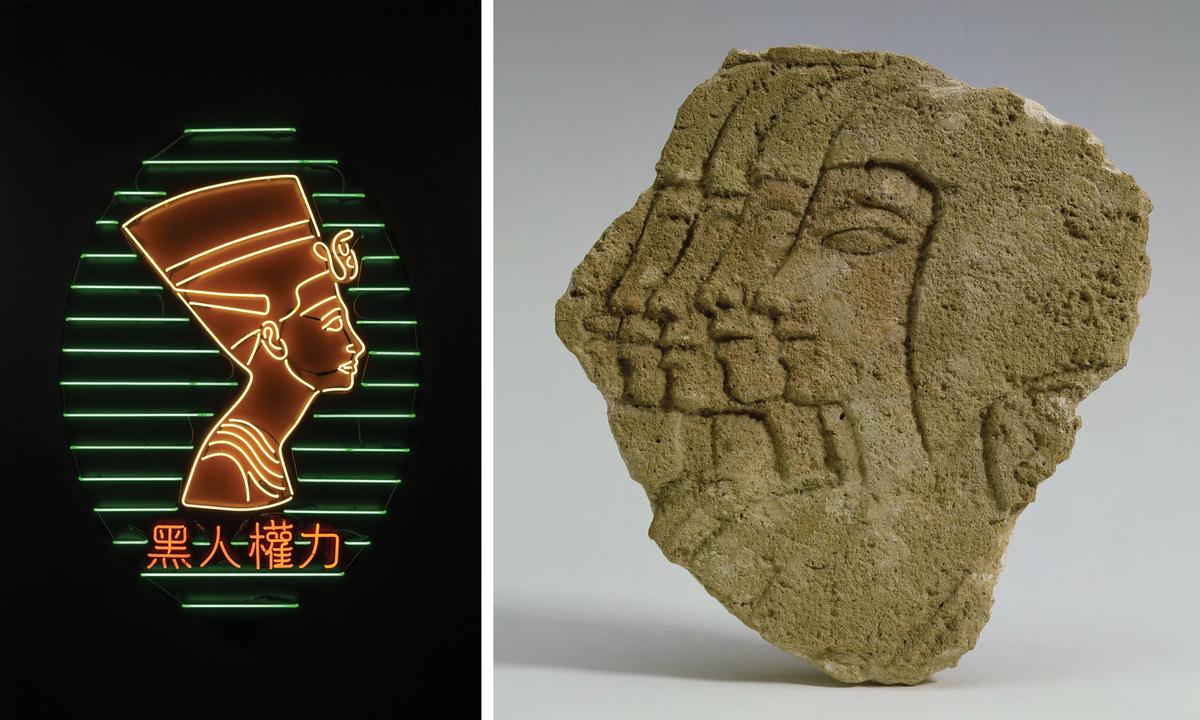

Visions of Ancient Egypt not only aims to untangle the ways in which Egypt’s image has been shaped by the West, but it also includes works by Modern and contemporary Egyptian artists who critique the constructed visions of their Pharaonic ancestors. Shown in the final section of the exhibition, it will display artists including Awol Erizku, Chant Avedissian, Maha Maamoun and Sara Sallam. Sallam’s multidisciplinary work The Fourth Pyramid Belongs To Her (2016-18) explores the odd dichotomy of the Pyramids of Giza as both a busy tourist site and actual mausoleums once considered sacred.

Plate 1 from Sara Sallam's series The Fourth Pyramid Belongs To Her (2017) Courtesy of the artist and Tintera Gallery

Sallam created the work while processing the passing of her own grandmother, and transposed photographs from the family archive onto images of the archaeological site and snapshots taken from Egyptian popular culture. “We look at mummies and consume them visually without a connection at all. We no longer experience Ancient Egyptian sites as places of mourning,” Sallam says. Research for The Fourth Pyramid Belongs To Her led Sallam to historical material like documents from Napoleon's campaign in Egypt. “How they were documenting Egypt affected our perception of the locations that we now call ‘archaeological’ or ‘touristic’,” she says.

For the show’s accompanying publication, Sallam has written a text explaining how she realises that even her own perspective as an Egyptian is, in fact, influenced by Western interpretations. “I see my work as a reflection of my ongoing journey of unlearning the exoticism of my own ancient heritage,” she writes. “Reclaiming the representations of my ancestors and finding ways of decolonising my gaze.”

• Visions of Ancient Egypt, Sainsbury Centre, Norwich, 3 September-1 January 2023. The exhibition is sponsored by Viking