Jaider Esbell, a Brazilian Indigenous artist of the Macuxi people who killed himself in November, aged 41, is at the heart of Cecilia Alemani’s Venice Biennale with 13 paintings on display in the Arsenale.

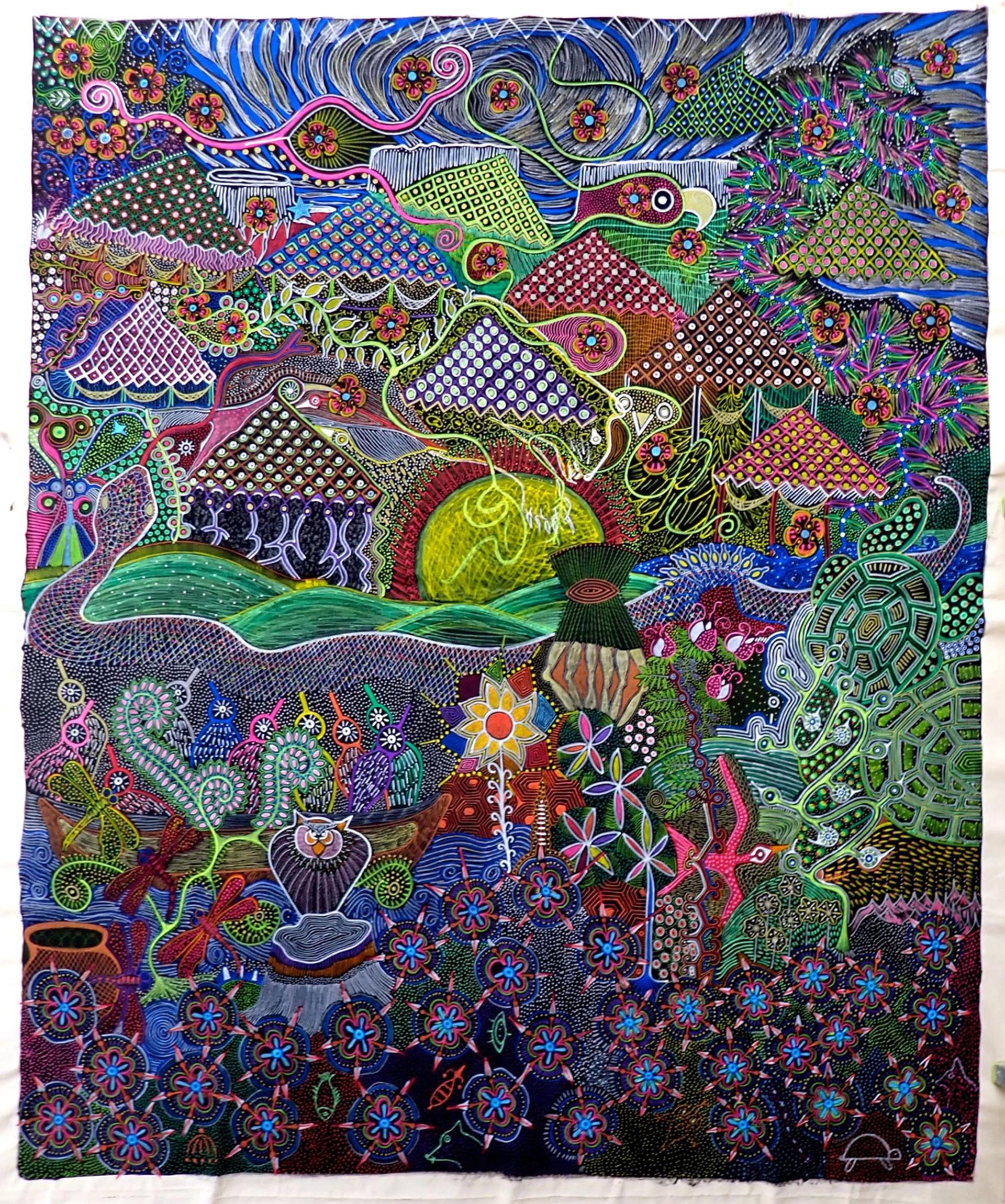

The intricate, highly detailed canvases combine Indigenous cosmology and mythology. Several tell stories of Makunaimî, the great ancestor of the Macuxi tribe. Others reference the ecological devastation that colonialism and capitalism bring in their wake.

Jaider Esbell's works shown in The Milk of Dreams exhibition at the 2022 Venice Biennale.

The display follows Esbell’s inclusion in the latest edition of the São Paulo Biennial, which closed in December, and a solo exhibition at Galeria Millan in São Paulo last February which included around 60 works. In the space of a few short months, Esbell went from being virtually unknown outside the Indigenous art community to being one of the fastest rising stars of the international art world. In October, the Pompidou Centre in Paris acquired two of his paintings. Next month, his work will be included in a Fondation Cartier exhibition in Lille.

"It was all too fast for him and I really, really regret what happened," says Jose Olympio Pereira, the president of the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, which organises the São Paulo Biennial.

In an online post published after Esbell’s suicide, his friend and fellow Indigenous artist Denilson Baniwa explained the pressure that comes with success in the mainstream art world: "Esbell was incorruptible in one thing: the desire to build an art scene where Indigenous people could have an active voice and a chance of maybe reaching the top, a place where we had never been before. Jaider reached this place, what for the whites is considered success (or 'the best phase of his career,' as I read in newspaper articles), but for both of us this fake-white-success was day by day becoming a burden. Unfortunately, the burden became too heavy for him…the pressure not to fail in our journey or in relation to our Indigenous relatives; the continuous hunger of those who see us as a devourable novelty in the market—all this creates a wall that surrounds us and takes us away from what is most important: a healthy life."

Jaider Esbell's Festa na Floresta, (2018). Photo: Marcelo Comaco

Esbell’s work was brought to Alemani’s attention during the pandemic lockdowns. "I couldn’t travel for research, so I asked a number of advisors—curators and museum directors from around the world—to help me research and Esbell’s name came up multiple times. I was in touch with him and I got his portfolio. Then, I flew to São Paolo to see the biennial and to meet him. It was the weekend he committed suicide so I never got the chance," Alemani says. "At that point, I had not yet invited him to participate in the Venice Biennale. It was a very sad coincidence. It’s very sad because he has been doing really important work in supporting other Indigenous artists from Brazil. When I was there, not only was he in the São Paulo biennial, he had also organised a show of indigenous artists."

Esbell was born in 1979 in Roraima, a sparsely populated state in northwest Brazil which borders Venezuela and Guyana and is home to the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous territory. A tireless champion of Indigenous communities through his art and activism, Esbell also ran the Jaider Esbell Contemporary Art Gallery which he founded in Boa Vista, Roraima, in 2013 to show the work of Indigenous artists.

From Jaider Esbell's series A Guerra dos Kanaimés (War of Kainamés) (2020), commissioned by the São Paulo Biennial Foundation for the 34th Biennial

“I have been working for 10 years in a deep immersion in my culture, seeking to connect with the world, proposing several dialogues through different artistic languages,” Esbell said in an interview last year. His aim, he said, was to “expand the Indigenous movement through the arts.” And he believed in the power of art and artists to change the world.

“Maybe the work of Indigenous artists and many other non-Indigenous artists are conversing very easily, very often fluidly,” Esbell said. This connection between artists brings with it "the possibility to reflect deeply about our presence and our action in this life and on this planet."