The optical illusions of the Dutch printmaker M.C. Escher (1898-1972) began finding mass appeal in the 1960s when they won a die-hard following among everyone from Mick Jagger, who had hopes of collaborating with Escher on a Rolling Stones record cover, to the British mathematician Roger Penrose, who regarded Escher as the great visualiser of scientific concepts.

Escher’s images and their knock-offs ended up adorning countless student walls and textbooks. And while his work has inspired film-makers and video-game designers this century, the art world proper has seemed like an odd man out, inclined to regard Escher, whose finished prints share formal qualities with Surrealism and Op art, as somewhat derivative or merely decorative. That is sure to change this month when the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston (MFAH) mounts a major exhibition on the artist titled Virtual Realities: the Art of M.C. Escher from the Michael S. Sachs Collection.

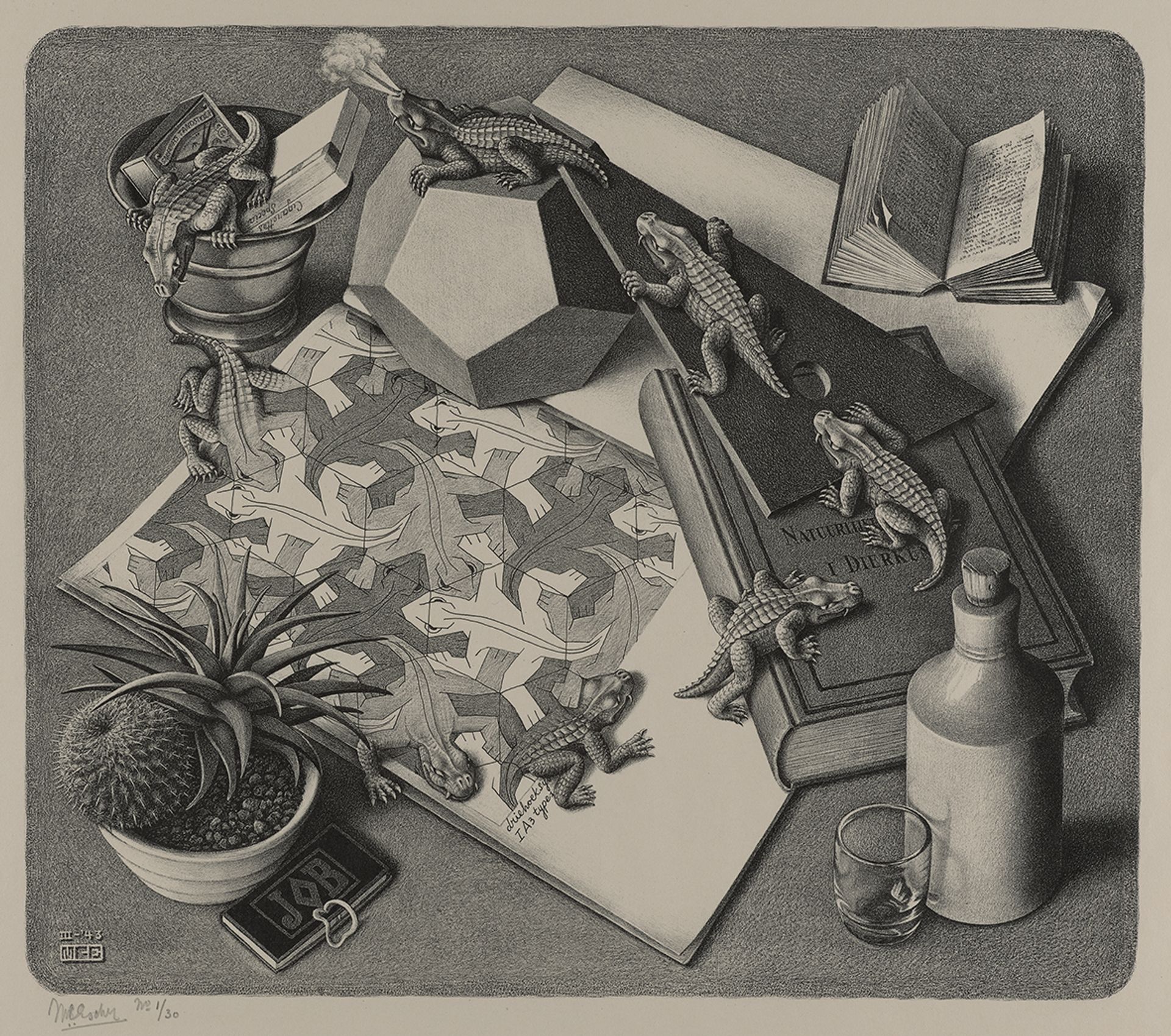

The lithograph Reptiles (1943), one of the artist’s most famous and widely reproduced works, is among more than 400 pieces in the Houston show © The M.C. Escher Company, The Netherlands; courtesy of Michael S. Sachs

With around 200 prints, more than 100 drawings, Escher’s original printing blocks and stones, and even his own print cabinet, the Houston show, with a total of more than 400 objects, is set to be the largest and most comprehensive exhibition dedicated to the artist to date.

Maurits Cornelis Escher died 50 years ago this month at the age of 73, but the reason for the exhibition—a late substitute for another MFAH show that fell victim to the pandemic—is Michael S. Sachs’s decision to open up the core of his collection, which took shape in 1980 when he acquired around 90% of Escher’s legacy in one fell swoop.

Now 84 years old, Sachs, a one-time clinical psychologist based in Connecticut, could be described as an Escher entrepreneur, combining the pleasures and obligations of collecting with the financial rewards of dealing. He had begun selling Escher prints in the early 1970s, and an existing relationship with Jan Vermeulen, Escher’s business adviser and executor, led to Sachs purchasing the bulk of the estate—rich in the artist’s unique works and containing a vast supply of prints—from Escher’s heirs. Sachs says he paid “about $1m” and over the subsequent years “sold about half” of what he had bought. However, he adds that he has been careful to keep the unique objects together, especially over the last decade or so.

Version subversion

Dena M. Woodall, the museum’s curator of prints and drawings, says Sachs’s prints are “impeccable,” having been stored under ideal conditions, rather than “up on his walls”. Escher was fascinated by the contrast between black and white, and he was highly sensitive to the type of paper he used to make the prints, which, apart from the lithographs, he did himself. Those subtleties are lost in reproductions, and the chance to see “the actual works” should be an eye-opener, she says.

Famous works on view will include the 1948 lithograph, Drawing Hands, showing two hands carefully sketching each other, and the Reptiles (1943) lithograph in which lizards seem to emerge from, and descend back into, a drawing. These are so well-known that you can almost see them with your eyes closed, but considering the whole of Escher’s oeuvre, they amount to something like an optical illusion—the black-and-white tip of an iceberg concealing a host of colourful marvels.

After experiencing the Islamic decorations of Spain’s Alhambra complex in the 1920s and 30s, Escher began creating sketches of tessellations, or elaborate patterns formed out of interlocking shapes, and these works, often in colour, went on to inform motifs in his prints. He called the drawings “symmetries”, and there are many on view in the show. In Symmetry No. 62 (1944), interlocking red-and-blue creatures are rendered in coloured pencil, ink and watercolour.

Neverending story

Escher also liked to use colour in some of his final prints, and Path of Life III (1966), a red-and-black woodcut, shows a geometric agglomeration of interlocking, ever-diminishing fish, in the kind of depiction of infinity that fascinated Penrose and his mathematician colleagues. The show will also include the woodblocks Escher used to construct his images, such as the tone block used to create the 1938 print Day and Night, which juxtaposes an interplay between light-and-dark birds flying over a light-and-dark village. Sachs says he himself is “partial to the woodcuts”, which Escher hand-printed without the use of a press.

Escher’s popularisation—and what some might call his bastardisation—will be addressed in the show in a blacklight poster room displaying bootleg Escher images produced in psychedelic colours. Meanwhile, a place for the genuine article in fine arts institutions seems secure. Washington DC’s National Gallery of Art is planning its own round of Escher events in 2023, and Sachs is considering what to do with his collection. “It must stay together, and it must go into a museum,” he says. “Finding the proper museum is a bit of a job and I’m working on it.”

• Virtual Realities: the Art of M.C. Escher from the Michael S. Sachs Collection, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 13 March-5 September