The art dealer Semjon H.N. Semjon is fighting eviction from the gallery in Berlin’s Mitte district that he has occupied for 21 years, with a petition and a legal challenge against his landlord, a property company majority-owned by the billionaire investor and art patron Nicolas Berggruen.

The building was renovated in 2019, forcing Semjon to close his gallery, although he says he continued to pay rent during the refurbishment. His request to the building’s managing agent, Czarny & Schiff, for compensation for the loss of income was rejected, he says. Instead, his rental agreement was terminated last year. His deadline to move out was 31 December 2021.

But Semjon is staying put for now and has engaged the Berlin art lawyer Peter Raue to fight his case. “This could take a while, and that suits me, because it would be too much to move out quickly,” Semjon says. “I have to look around for a new place. But rents have exploded and I can’t afford them.”

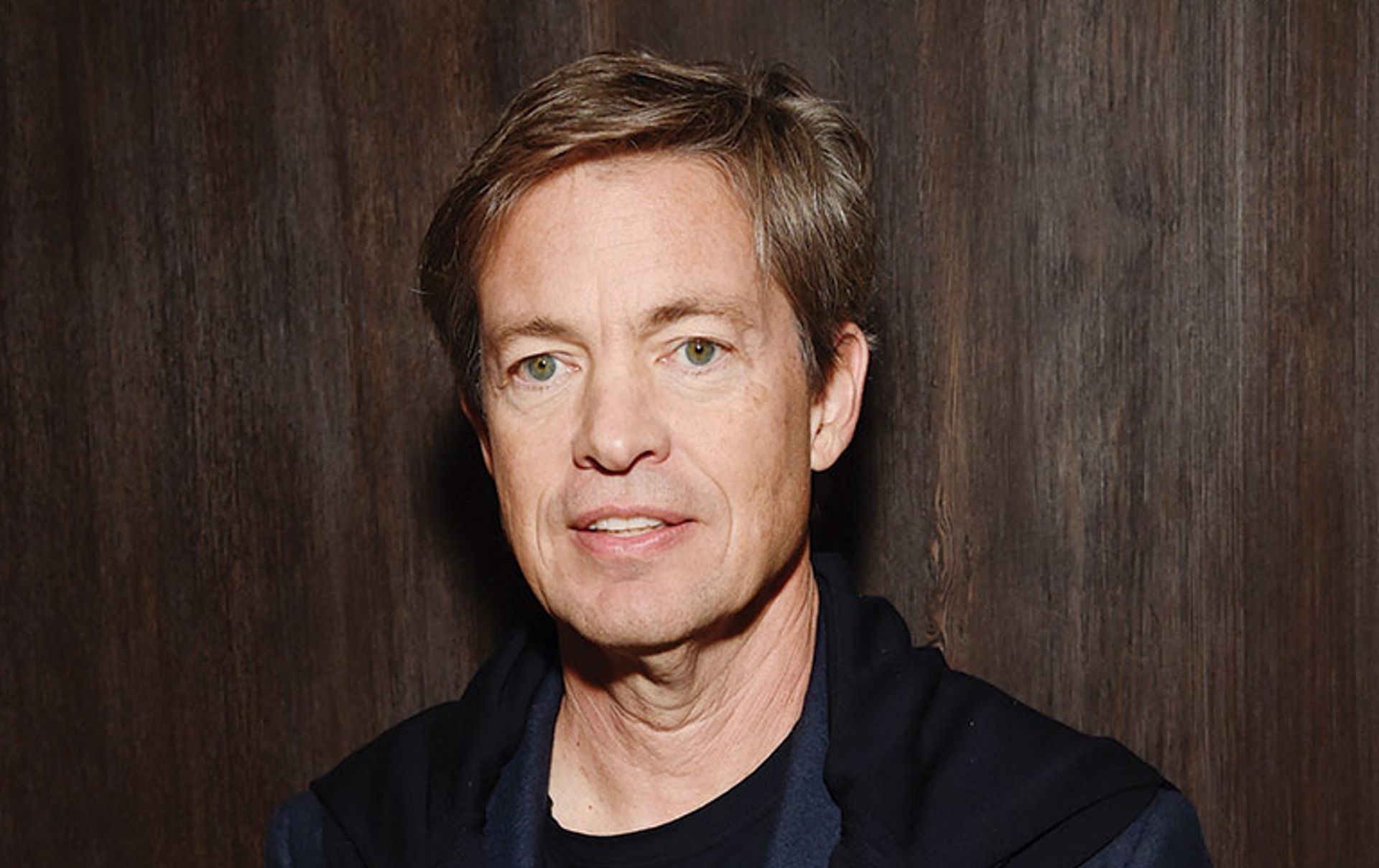

Berggruen and his family recently pledged €1m a year to support the museum founded by his father Photo: Michael Kovac/Getty Images

The story of Berlin art spaces falling victim to rising rents and gentrification, and being forced to close, is not a new one. But Semjon is particularly aggrieved that Berggruen, who is known for his commitment to contemporary and Modern art, should seem indifferent to the fate of his gallery, Semjon Contemporary. Berggruen and his family agreed in September to donate funding of €1m annually for exhibitions and events at Berlin’s Museum Berggruen, founded by their father, the collector Heinz Berggruen.

Semjon has rallied support for his gallery’s continued existence in its present location from four members of parliament, including the former Berlin mayor, Michael Müller. In an open letter addressed to Nicolas Berggruen, they appealed to his passion for the arts. “Given your engagement it is surprising that after Berggruen Holdings acquired the building, your company would terminate the rental agreement with a small gallery for contemporary art in Berlin Mitte,” they wrote in a letter dated 15 December 2021. “It is precisely small galleries, free spaces for artists, decentralised cultural businesses and local offerings that—alongside the big museums and collections—determine Berlin’s self-image and quality of life.”

A petition on Semjon’s website urges Berggruen to reconsider and points out that Semjon has helped to make the street and the building desirable from an investment perspective. But Samuel Czarny, the managing director of Nicolas Berggruen Holdings, says in a press statement that Berggruen himself “is not active in the operative management and not involved in these processes”.

Nicolas Berggruen Holdings owns 60% of the building: the remaining share is the personal property of Czarny and his business partner, Ariel Schiff, who are fully responsible for managing it, Czarny says. Czarny accused Semjon of “dishonourable conduct” and waging a “defamatory campaign” to remain in the building. Czarny also argues that in violation of his contract, Semjon never sought approval for a site-specific installation that he created in the building as an artist before he became a dealer.

Semjon says moving location would require him to destroy his installation, KioskShop Berlin. Viewed by thousands of visitors between 2000 and 2010, it was hidden behind walls in his gallery for ten years. Semjon reopened it to the public in October, when he received notice of his eviction. It is a small shop, complete with “product sculptures”—Coca-Cola cans, newspapers, washing powder packages and more covered in a bleached beeswax that renders everything white but still recognisable.

“I have exposed my KioskShop again to show what will be destroyed,” Semjon says. “I am using it for communicative leverage.”