Crowds marched through the streets of Florence unfurling banners with ‘Hands Off Our Heritage!’

In the summer of 2020, the Uffizi Galleries in Florence hired the arts educator Justin Randolph Thompson to deliver a series of online lectures about Black figures in Old Master paintings. Thompson was to discuss eight artworks featuring people of African descent, painted between the 15th and 18th centuries. Sadly, though perhaps predictably, the initiative sparked a protest by far-right groups. Crowds marched through the streets of Florence with lit flares, unfurling banners with slogans like, “Hands Off Our Heritage!” Online, the invective poured in: “Pathetic and ridiculous,” wrote someone on Facebook. “Reinventing history in the name of political correctness,” was another comment.

What the protesters likely had not grasped is that the paintings in question were already part of the permanent collections of the Uffizi and its sister museum. They had not been specially brought in for the talks. (Whether the pieces were on permanent display or in storage I do not know.)

The lectures were not, as the protesters believed, an attempt to rewrite Italian history but rather were an unearthing of it, an airing of what had literally always been there.

Thompson wanted to challenge the idea that historical paintings are purely the legacy of white Europeans. He included such pieces as Piero di Cosimo’s Perseus Freeing Andromeda (around 1510-15), which depicts a Black female musician, as well as portraits of Duke Alessandro de’ Medici, who ruled Florence and its territories from 1532 until his assassination in 1537. Known as “the Moor” because of his darker complexion, Duke Alessandro was the son of Lorenzo II de’ Medici and an African servant in the Medici household.

Thompson said he had found “a certain reluctance towards acknowledging the existence of Black African royalty” in the age of the Renaissance. “Any conversation about Blackness in that space is a challenge to the existing order.”

Esi Edugyan © Esi Edugyan

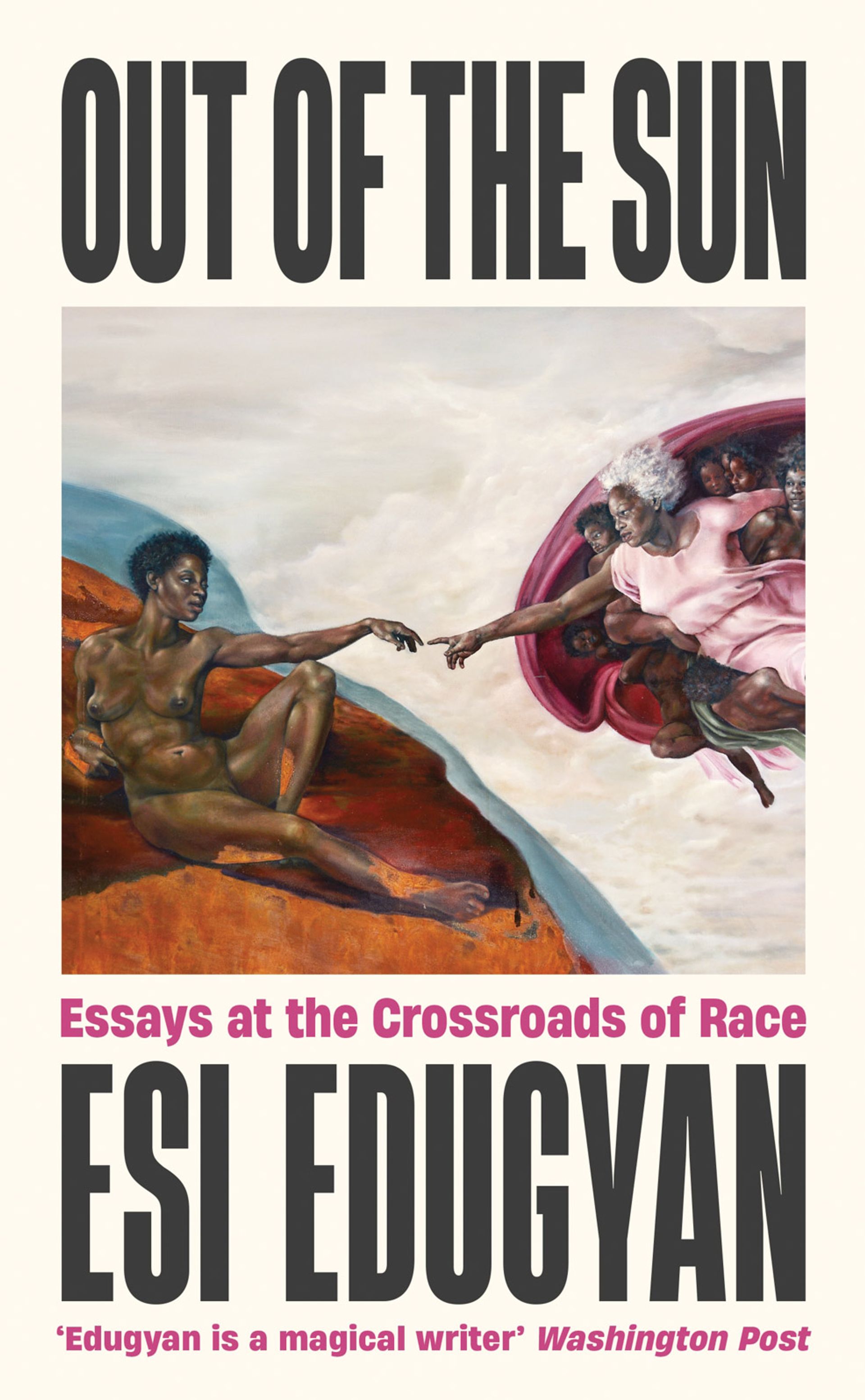

Similarly controversial was a 2019 exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Called Black Models: from Géricault to Matisse, the show took masterpieces by some of France’s most celebrated artists and debuted them with new names. The paintings were all renamed in honour of the Black subjects depicted in them. The idea, I think, was to remind the viewer of the indelible presence of Black people in France for centuries. The curators were attempting to put paid to the lie of a purely white France only recently changed by mass migration; they wanted to show that no aspect of Western development happened without the hand of the “other”.

As an example, Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of a Negress (1800) was renamed after the model depicted: Madeleine. In reclaiming her name—however contentiously it was bestowed on her—the subject was to regain some measure of her humanity.

I am of two minds when it comes to this kind of restitution. Though I understand what a powerful act naming is, and the impulse to reframe and recontextualise things for our time, I understand too how certain historic resonances can be lost. In the case of older portraits, the names were often not artist-given: they were bestowed after the fact by vendors and gallerists and curators, and may not have reflected the artist’s intention. This might be the case for Benoist’s Portrait of a Negress, and if that is so I wholeheartedly support the change to Madeleine.

In the case, though, where the name was chosen or sanctioned by the artist, things grow a little thornier. But it seems to me that while original titles may carry within them the distasteful and accepted prejudices of the worlds in which they were chosen, they force us, in their offense, to look hard at the social climate and circumstances of those worlds. I do not at all care for Joseph Conrad’s title, The Nigger of the “Narcissus”, but I could not imagine the novel being called otherwise. It bears witness to the ugliness of a time and mindset in which such epithets were an accepted and neutral thing.

Perhaps one solution, in the case of visual art, would be for the work to bear both titles, an “original” and a “contemporary” one. The gulf between them would say much about the past and about the progress we have made, and how much further we have to go.

We too will be judged, and judged harshly, by those who come after us. We cannot know now how we will offend. But our offences will become the yardstick by which future generations can measure themselves.

• Out of the Sun: Essays at the Crossroads of Race, Esi Edugyan, Serpent’s Tail, 256pp, £16.99 (hb), © author

![Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of a Negress (1800) was renamed Portrait of Madeleine in a recent exhibition. “In reclaiming her name [...] the subject was to regain some measure of her humanity,” writes Edugyan Image courtesy of Musée du Louvre](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cxgd3urn/production/6195244bfe1563a0b4cb1c2d42162efc2524c84d-1296x1600.jpg?rect=0,0,1296,1599&w=1200&h=1481&fit=crop&auto=format)