Since Zurich’s Kunsthaus opened an imposing extension in October, the museum has faced a wave of criticism over its long-term loan display of the arms dealer Emil Georg Bührle’s controversial collection of Impressionist and post-Impressionist art. The outcry is spurring action from the city government and a debate in the Swiss national parliament that could see an overhaul in the country’s approach to returning Nazi-looted art.

Among the critics of the new Bührle displays are former members of the Bergier Commission, an international panel of scholars appointed by the government to investigate Swiss financial dealings during the Second World War. In a statement 20 years after the commission published its final report, the scholars called the situation in Zurich “an affront to potential victims”.

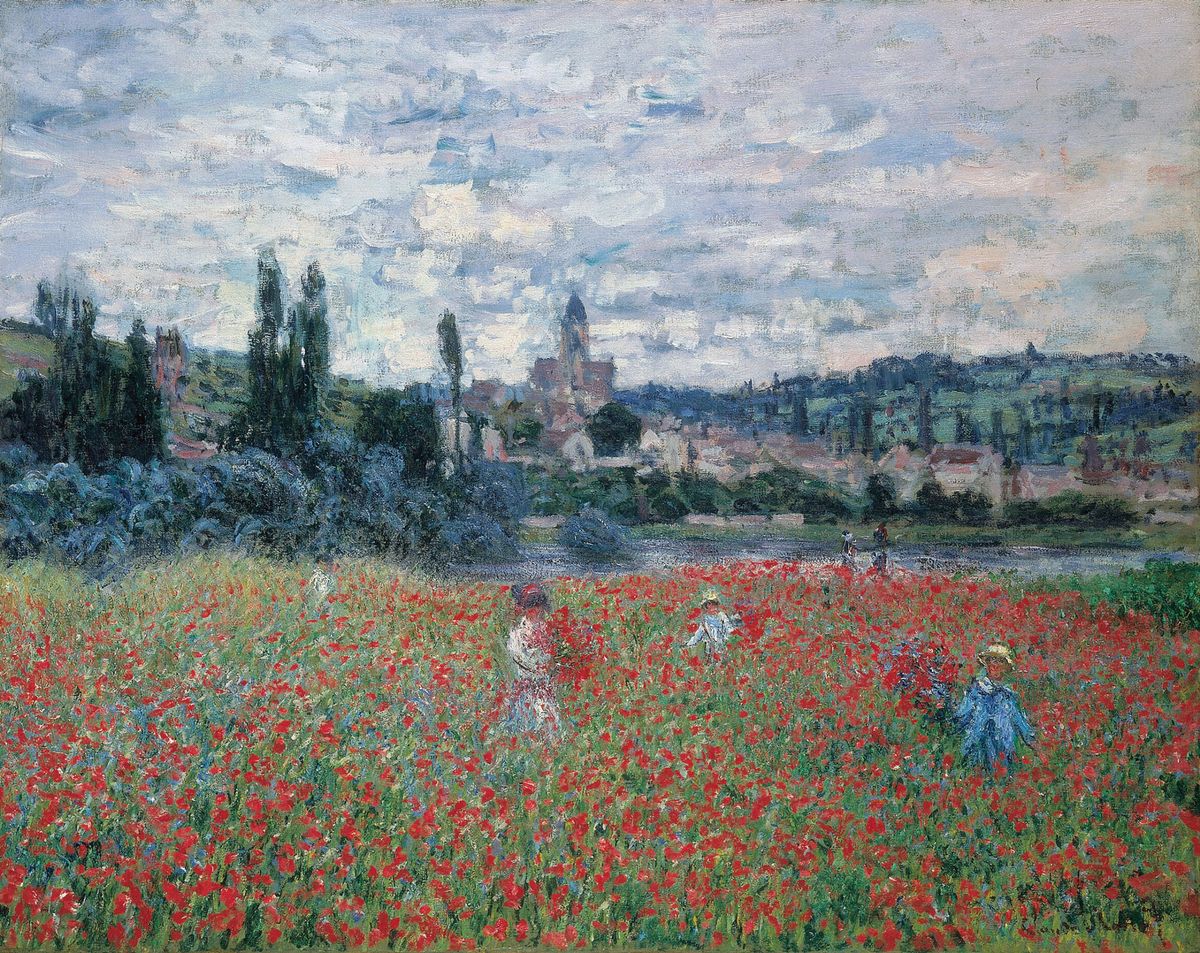

Bührle’s company sold anti-aircraft cannons to Nazi Germany during the war and profited from slave labour. The industrialist also purchased art that was confiscated from Jews. The Bührle Foundation maintains that none of the 200 works it has loaned to the Kunsthaus are looted, but at least one painting faces a claim from the heir of a Jewish collector.

In response to the Bergier Commission’s demands, the city of Zurich pledged in November to conduct an independent evaluation of the Bührle Foundation’s provenance research and to work with the Kunsthaus to develop its existing historical display about Bührle’s career and the origins of the collection. Meanwhile, Lukas Gloor, the longstanding head of the Bührle Foundation, has announced that he will step down at the end of the year.

At the national level, the lawmaker Jon Pult is backing a motion urging parliament to take action on another of the Bergier Commission’s demands by setting up an independent panel to assess claims for art lost due to Nazi persecution in Swiss museums. “The story of the Emil Bührle collection has shown that the subject is bigger and more explosive that people realised,” Pult says. “We need better instruments.”

Switzerland was one of 44 governments and organisations that endorsed the non-binding Washington Principles on Nazi-looted art in 1998. Under these principles, governments agreed to encourage museums to conduct provenance research, identify works of art seized by the Nazis and seek “a just and fair solution” for them with the original Jewish owners and their heirs.

The principles also called for “alternative dispute resolution mechanisms for resolving ownership issues”. Five European countries have independent panels to assess claims: Germany, Austria, France, the Netherlands and the UK. But Switzerland, which served as a hub for Nazi-looted art before and during the Second World War, has so far not done so.

Until now, the Swiss government has argued that there are not enough cases to warrant such a panel. But Benno Widmer, the head of the museums and collections department of Switzerland’s Federal Office for Culture, has said that “if the need intensifies due to an increasing number of contentious cases, then the demand for an external commission could be re-examined”.