Since the early 1990s, Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan has been considered one of contemporary art’s most high-profile provocateurs. His praying schoolboy Hitler (Him, 2001), meteorite-struck Pope John Paul II (La Nona Ora, 1999) and fully functioning 18-carat gold toilet (America, 2016) have all garnered headlines. But Cattelan surpassed himself with his 2019 showstopper at Art Basel in Miami Beach. Comedian was just a banana attached to the wall with grey duct tape—but the conceptually audacious, over-ripe readymade drew crowds and divided critics. We asked Cattelan about his work on show this year at the fair—and how his art resonates in the age of Covid.

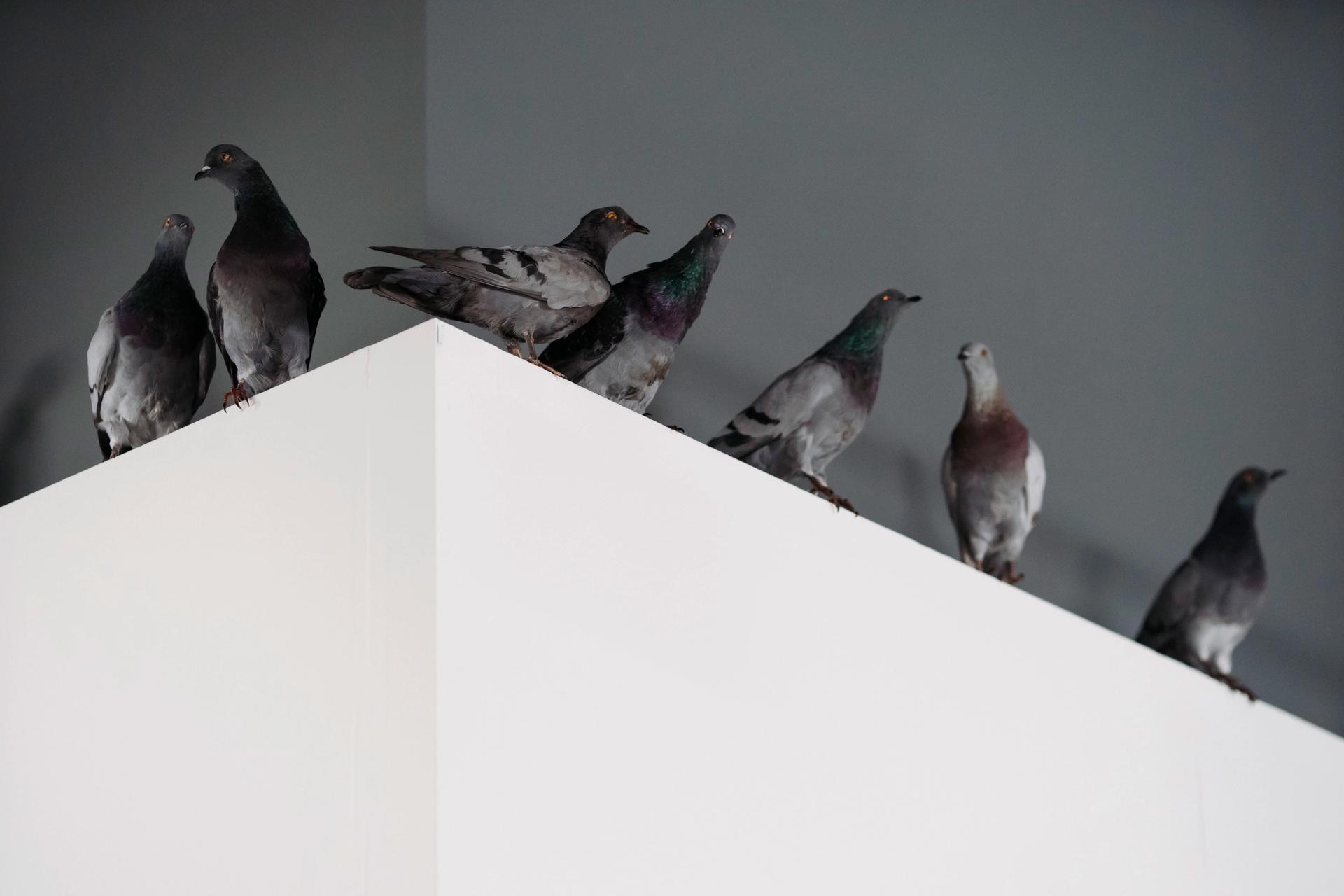

Your work on Perrotin’s stand is the latest in a long line of pigeon installations, from Turisti (Tourists) at the Venice Biennale in 1997 to the current intervention at the Pinault Collection in Paris (Others, 2011). Why bring this flock of birds to Art Basel in Miami Beach?

I am questioning the nature of how we display art, which is particularly important in the rigidity of an art fair. The pigeons are “observing” from above the movements of the visitors below, suggesting a different confine between inside and outside, what is seen and who is seeing. We live in a society where we are under constant surveillance, like being in The Truman Show; up to the very end you don’t know if you're the subject or object of what’s going on.

And I titled them Ghosts maybe just because they appear to be overseeing us and we never know whether they are friends or foes, but also because as ghosts they live in a “suspended” dimension; it’s never clear where exactly they are.

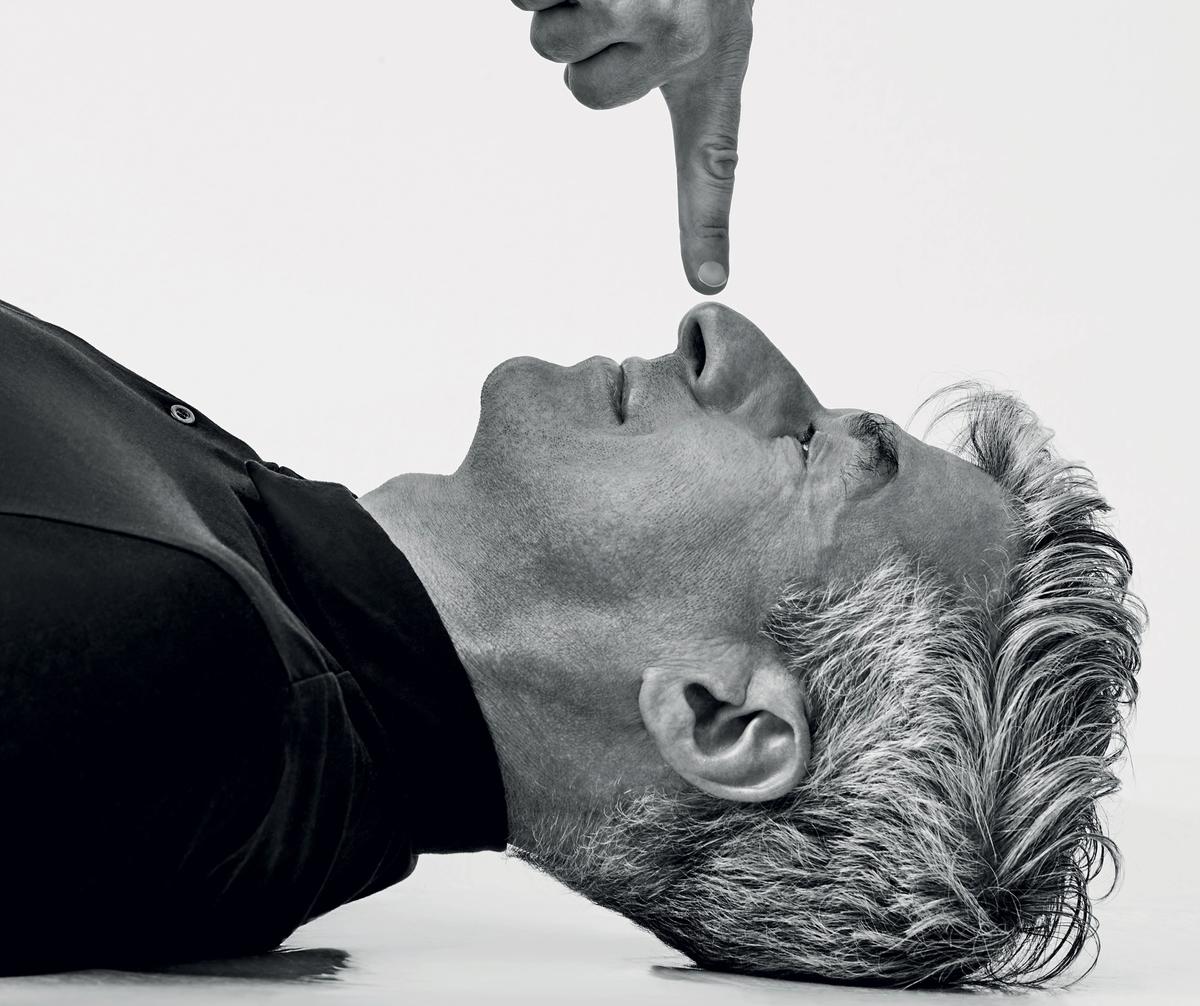

Dealer Emmanuel Perrotin checks himself out in Maurizio Cattelan's new sculpture, Nothing (2021) at Art Basel in Miami Beach.

Photo: Eric Thayer

Do you think you’ll be able to top the viral sensation of Comedian?

To me, Comedian was not a joke; it was a sincere commentary and a reflection on what we value. At art fairs, speed and business reign, so I saw it like this: if I had to be at a fair, I could sell a banana like others sell their paintings. I could play within the system, but with my rules. I can’t say how people will react, but I hope these new works will break up the normal viewing habits and open a discussion on what really matters. We are surrounded by conversations based on immaterial structures, social values and hierarchies that we created, but usually we prefer to forget this; it’s like being anaesthetised.

How do you think your irreverent art will be viewed in the post-pandemic period?

I am not sure about irreverent. We live in a society where people take in information at an unprecedented speed; everything is talked about. If no one is talking about it, it becomes uninteresting. This has only been heightened in the pandemic. Even controversy can be a tool, as long as the controversy is surrounding the reaction, and not the content, of the work. My practice is based on communication, so in this way the digital era might help it thrive.

Maurizio Cattelan's Ghosts (2021) perched above Perrotin's stand at Art Basel in Miami Beach

Photo: Eric Thayer

Do you think that, over time, you’ll be revered or reviled by art historians?

Are they not two sides of the same coin?

Do you think it is true that, as Warhol said, “art is whatever you can get away with”?

Art is a way of communicating thoughts, so I think a work is only successful when it speaks to your audience. So, I agree in the sense that the reaction determines success. But you have to make something that speaks to people first. I am always at risk of making a fool of myself because if no one reacts to the work then it would not work. When art makes us feel something and puts us in a position of discomfort, that’s when it has an impact. Warhol, and in some ways Beuys as well, understood this perfectly: we can be revolutionary even without being ideological or signing a manifesto, otherwise we’re just making propaganda.

Should all your works, from La Nona Ora (1999) to America (2016), be viewed and interpreted in an absurdist context?

Life is often tragic and comedic at the same time, and my works address these two facets. I use playfulness to express myself or to approach sensitive subjects, but not to make fun of anyone or to make people laugh.

An artwork is a symbolic action and always brings together rational and unconscious thoughts: it’s a sort of marriage and what I want to show is exactly the complexity of opposites encountering each other, life and death, hatred and love.

Maurizio Cattelan's work Blind is a response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks

Photo: Agostino Osio; courtesy the artist, Marian Goodman Gallery and Pirelli HangarBicocca

Why was it important to show Breath Ghosts Blind—your response to the 9/11 terror attacks—at the Pirelli HangarBicocca earlier this year?

Breath Ghosts Blind is a work about pain and its social dimension; it is there to show the fragility of a society where loneliness and egotism are on the rise. I lived in New York in 2001, and I witnessed the attack on the Twin Towers from a taxi going to LaGuardia airport. The next day, it was like waking up in another world. It's a scar that's not sutured yet, even 20 years later.

Originally, I had wanted to show this work in New York. Covid-19 made it difficult, and some people refused the work, but Vicente Todolí, the artistic director of Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan, supported me. So far, it has not been controversial but my hope is that it will travel. Certain images, and objects, have an incredible symbolic power, and to me it’s really like turning a spotlight on matters that concern us, even when that means taking risks, causing annoyance or thinking differently.