Tate Britain in London has defended the approach taken in its Hogarth and Europe exhibition (until 20 March 2022) following a wave of criticism focused on wall labels written by contemporary commentators, which one critic described as “wokeish drivel”. The museum’s director, Alex Farquharson, tells The Art Newspaper that “Tate Britain has both the confidence to provide a public platform for those conversations and the expertise to contribute to them directly.”

The exhibition, curated by Alice Insley and a former Tate senior curator Martin Myrone, presents William Hogarth’s work in a “fresh light”, with his art seen for the first time alongside works by continental contemporaries in Venice, Paris and Amsterdam, such as Jean-Siméon Chardin of France (1699-1779). “A number of commentators were invited to write the shorter labels immediately alongside individual works. These texts bring a wider range of perspectives, expertise, and insights to the exhibition,” according to the exhibition wall text.

Great artists can be unpacked and interpreted anew by each generationAlex Farquharson, Tate Britain director

But the decision by Tate management to include commentaries on Hogarth’s paintings by several non-curatorial figures, including the artists Lubaina Himid and Sonia E. Barrett, inflamed UK national newspaper art critics.

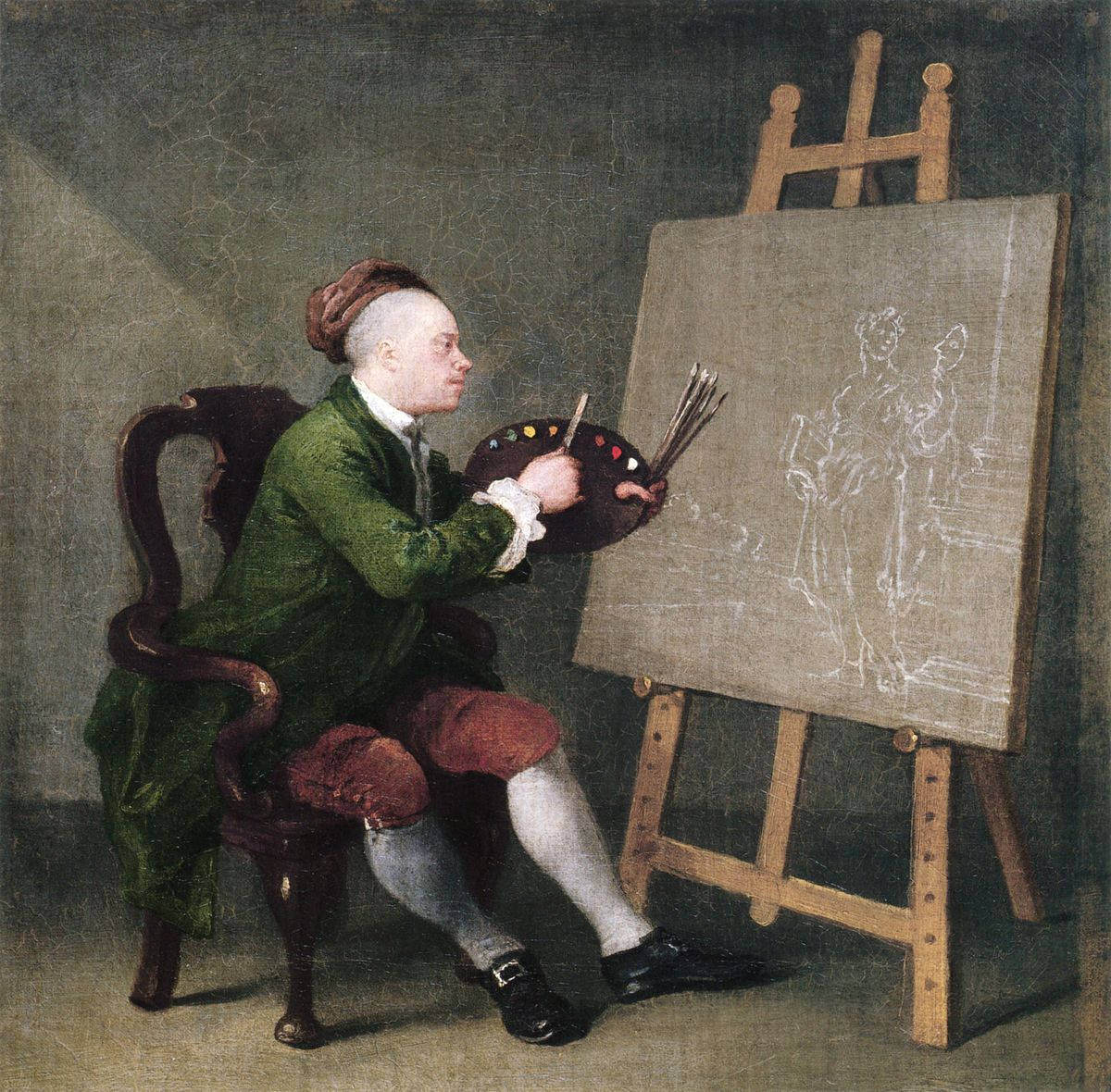

According to a wall text written by Barrett, for example, a 1757 self-portrait showing Hogarth sitting on a wooden chair should be seen within the context of slavery. “The curvaceous chair literally supports him and exemplifies his view on beauty,” she writes. “The chair is made from timbers shipped from the colonies, via routes which also shipped enslaved people. Could the chair also stand in for all those unnamed black and brown people enabling the society that supports his vigorous creativity?”.

In response, under a headline stating that the 18th-century artist had been “yanked into today’s culture wars”, the critic Waldemar Januszczak wrote in the Sunday Times that “[a problem] is the collapse here of useful scholarship and its replacement by wokeish drivel. Caption after caption wastes precious explanatory space on à la mode speculations about Hogarth’s intentions that are thunderously unreliable.”

Fashion statement: Hogarth’s Marriage a-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête (around 1743) The National Gallery, London

Rachel Cooke wrote in the Observer: “Nor was I keen on its curators’ painfully extreme anxiety towards social attitudes in this period; to the connections of some of its subjects to colonialism and slavery; to sexism and antisemitism. They treat the work like bombs that are about to detonate.” Jackie Wullschläger of the Financial Times lamented the fact that the exhibition catalogue cover has no picture, prompting her to declare: “Hogarth cancelled.”

The image-free cover of the Tate Britain exhibition catalogue Photo: Martin Bailey; Tate

Farquharson stresses that the process of developing the interpretation strategy and inviting contributors is always led by the curatorial team, which includes colleagues with expertise in gallery interpretation. A UK museum consultant specialising in interpretation, who preferred to remain anonymous, says however that the Tate approach is “unusual”.

An ‘innovative approach’

Farquharson adds that staging such an exhibition reflecting the very latest Hogarth scholarship is a collaborative process, explaining that the exhibition team achieved this by bringing multiple voices into the interpretation texts alongside their own.

“Perhaps that’s an innovative approach to take on the gallery walls, but it’s how exhibition catalogues are often structured, and it’s familiar to us all from television documentaries where the presenter’s framing narrative is combined with multiple ‘talking head’ contributors,” he says.

Asked if Tate Britain has lost confidence in the way it deals with historic material, Farquharson says: “Great artists can be unpacked and interpreted anew by each generation—that’s part of what makes them so important. In this instance, I think Hogarth emerges from this process as an even more sophisticated and influential artist than we already knew.”