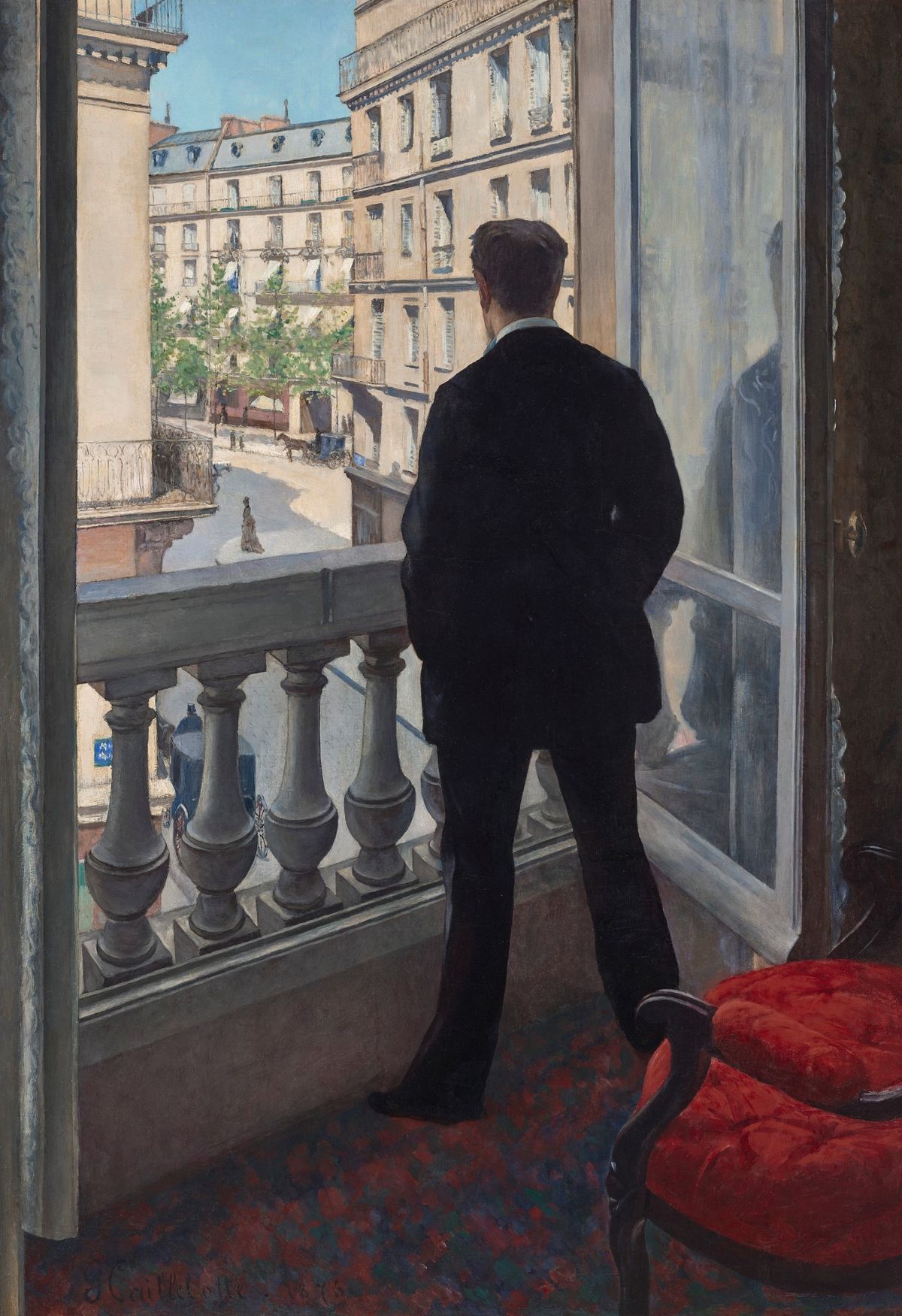

Los Angeles’s J. Paul Getty Museum continued its accumulation of 19th-century French masterpieces with the recent acquisition of Gustave Caillebotte’s celebrated urban scene Young Man at His Window, an 1876 painting showing the artist’s brother René staring down on a modern Paris street.

The Getty paid a record-setting $53m for the work, which was a centerpiece of the 11 November auction at Christie’s New York of the Impressionist collection of Edwin L. Cox, who died in November 2020. The hammer price was $46m, against an estimate in the region of $50m (auction house estimates do not include fees). Cox, a Texas businessman and philanthropist, purchased the work in 1995 from New York’s Wildenstein & Co. and then hung it above the desk in the office of his Dallas mansion, says Vanessa Fusco, Christie’s senior vice president and head of sales in the Impressionist and Modern art department.

For Getty director Timothy Potts, the work kills two birds with one purchase. Not only is the painting the Getty’s first Caillebotte, it is also the museum's first artwork associated with the Impressionists’ key second exhibition, held in 1876 at the Paris gallery of Paul Durand-Ruel. The work coming up for auction represented “a unique opportunity”, says Potts, adding, in regards to the museum’s winning bid, “We had to give it our best shot.”

The price itself recalls the Getty’s sensational purchase of Édouard Manet’s 1881 allegorical portrait Jeanne (Spring), which the museum bought for just over $65m at a Christie’s New York evening sale in 2014. But Scott Allan, curator of paintings at the Getty, is more eager to display the Caillebotte with an earlier Manet, 1878’s The Rue Mosnier with Flags. The new acquisition, showing the stark new buildings of Haussmannian Paris as viewed from an upper-floor window of a bourgeois apartment, “resonates in a fun way” with the urban Manet painting, which shows the street outside the artist’s second-story studio decked out for a national holiday.

Cox had kept Young Man at His Window out of public view for the last quarter-century, but it has nonetheless become one of the artist’s best-known works. “Art historians have loved to write about it for a long time,” says Allan. He adds that decades of social and feminist historians of art have been drawn to the painting because it addresses “the power dynamics of vision” as well as “the male gaze”.

Art historian Samuel Raybone, a lecturer in art history at Aberystwyth University in Wales who published last year’s well-reviewed monograph Gustave Caillebotte as Worker, Collector, Painter, says the painting is a work of “psychological intensity”. With its taut main figure and “disorienting manipulations of space”, it demonstrates “Caillebotte’s distinctive perspective on modern life” and singular contribution to Impressionism.

Allan says he expects the Caillebotte to go on temporary view in early 2022 before it is sent down to the conservation studio. “We need to have the conservators spend time with the picture and see what we find,” he says. “Some cosmetic work” may be needed on the painting’s darker areas, he says, but the actual street scene “is in beautiful condition”.

After emerging, the work will take its place in the Getty’s Impressionist holdings, housed in the complex’s west pavilion, which is now closed for renovations. Even before last week’s auction, Allan was busy planning for the pavilion’s reopening early next year, but the new acquisition has sent him back to the drawing board in deciding where to put what.

Young Man at His Window adds “a big note”, he says. “And I’m playing around again with my images.”