This December, Tate Britain will stage Life Between Islands (1 December-3 April 2022), a major exhibition charting the history of Caribbean-British art from the Windrush generation of the 1950s to today, which its director hopes will “de-centre our national remit and what it says about British society”.

Alex Farquharson, who is co-organising the show with the curator, writer and photographer David A. Bailey, first voiced his desire to mount such an exhibition during his interview to become the London museum’s director in 2015. “The Caribbean connection in British art across generations is rich and fascinating in itself,” Farquharson says. “It’s also fascinating for the insights it offers on how Britain has been reshaped by the Caribbean, which is of course a consequence of how Britain—during a long and violent history—reshaped much of the Caribbean.”

He felt this story needed “to be told on a large scale” and the show is certainly ambitious, covering 70 years of artistic practice and representing more than 40 artists of Caribbean heritage as well as those inspired by the Caribbean. Among them are Donald Locke and his son Hew Locke, Claudette Johnson, Sonia Boyce, Steve McQueen and Grace Wales Bonner.

Institutional recognition for these artists is also long overdue. Farquharson admits that “few of the artists working prior to 1990 were collected by Tate at the time”, although its collection has diversified over the past 15 years. In 2018, the artist Rasheed Araeen accused Tate of “persistent institutional racism” in rejecting his book and exhibition project for an inclusive history, The Whole Story: Art in Postwar Britain. Farquharson does not disagree: “It struck me on my arrival at Tate Britain that Chris Ofili had been the only Black artist to have a solo exhibition there [in 2010].”

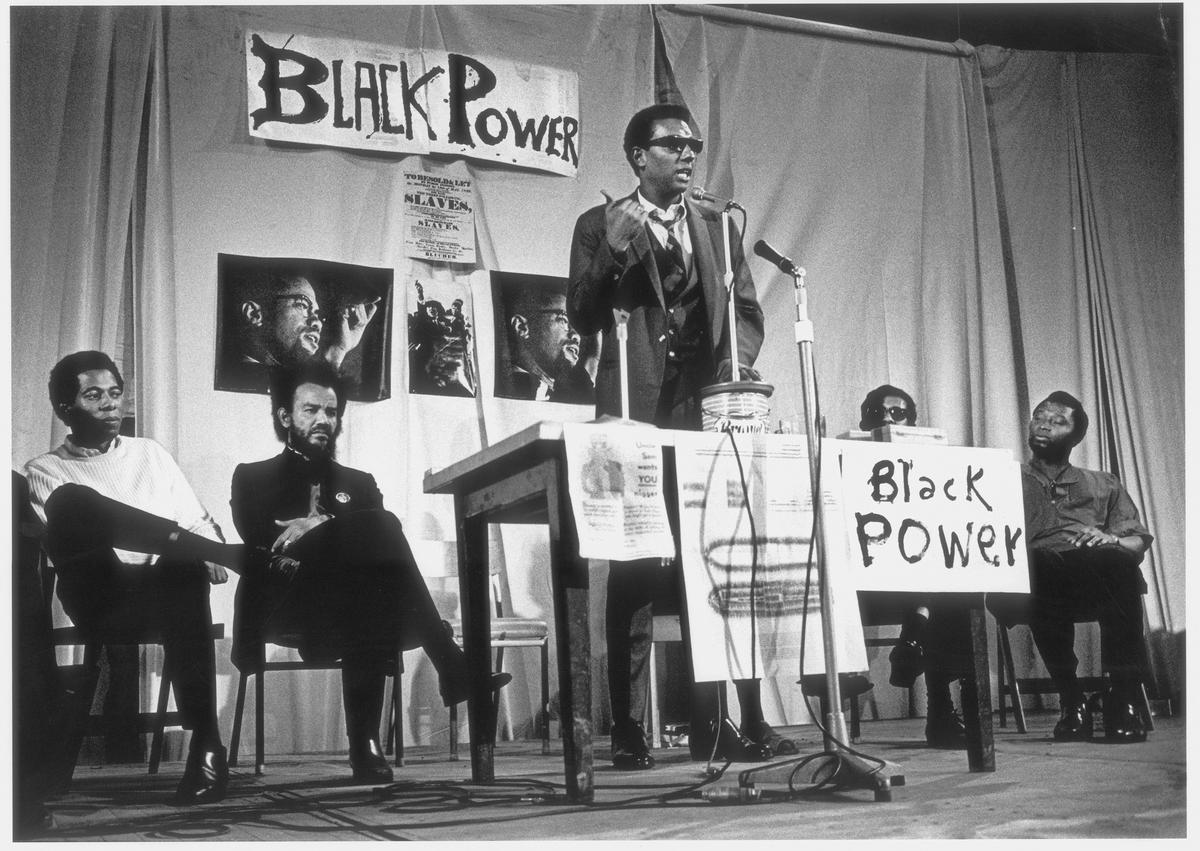

For decades, Caribbean-British artists were overlooked by the UK’s art establishment and, from this marginalised position, formed their own groups, such as the Caribbean Artists Movement in the 1960s and the BLK Art Group from 1979 to 1984. The Tate exhibition will be framed by these groups and key shows such as those curated by the artist Lubaina Himid in the 1980s, which championed Black women artists. In more recent history, Farquharson cites the influence of artists Peter Doig, Ofili, Hurvin Anderson and Lisa Brice in the early 2000s on the CCA7 residency programme in Port of Spain, Trinidad, which led Doig and Ofili to move there permanently.

From Windrush to Venice

Life Between Islands comes at a time of widespread interest in the work of artists of Caribbean heritage. Last year, Veronica Ryan and Thomas J. Price were commissioned by the London borough of Hackney to create new public sculptures celebrating the Windrush generation. Ryan’s large-scale trio of Caribbean fruits was unveiled this month, to be followed next June by Price’s work. (Meanwhile, he has a solo show at Hauser & Wirth Somerset.) And at the 2022 Venice Biennale, Boyce will be the first Black woman to represent the UK, Alberta Whittle will represent Scotland while Simone Leigh will be the first Black woman to represent the US.

Alberta Whittle’s Matrix Moves (2019) Courtesy of the artist and Copperfield, London

Barbados-born and Glasgow-based, Whittle has four works showing in Life Between Islands. Her practice explores the duality of her identity and Barbados plays a central role: she spent lockdown last year on the island making her film RESET, co-commissioned for the 2020 Frieze Artist Award and currently on view at Jupiter Artland near Edinburgh. At this year’s Frieze London, Whittle has a solo booth with Copperfield London, featuring a wall of bronze casts of her own tongue. “I was thinking about the fact that I have no idea what my mother tongue is, and about how our tongues communicate our ancestral histories,” she says.

Studying at the Glasgow School of Art a decade ago, Whittle was “the only Black artist on the course”, she says. “It’s only in the past five years that there have been more Black students.” The Grenada-born, Cornwall-based artist Denzil Forrester, who is also represented in the Tate show, had a similar experience in the early 1980s when he studied at London’s Royal College of Art. “I was the only one in my year who was Black,” Forrester says. “Coming from West Indian, Black or mixed-race heritage, it was unusual to go to art college.”

Forrester has painted all his life, drawing in the gloom of London’s underground nightclubs as studies for his vivid large-scale paintings of writhing bodies. In the mid-1990s, he organised several exhibitions, The Caribbean Connection, at the Black-Art Gallery. But commercial success came only recently, when he retired from teaching at Morley College and moved to Cornwall in his 60s.

Forrester had applied to galleries in the 1990s and early 2000s but “no one was interested”, he says. “I think my work was ‘too Black’.” A turning point came in 2016 when Doig requested a meeting. That triggered Forrester’s late career boom, as Doig organised shows for him that year at Tramps in London and White Columns in New York, then at the Jackson Foundation in St Just, Cornwall, in 2018. Forrester says he was courted by a few “smart Mayfair art agents” after that but, on Doig’s advice, signed with Stephen Friedman gallery.

London swings inwards

Farquharson points out that the Guyanese artists Denis Williams, Aubrey Williams and Frank Bowling—who came to the UK from what was still a British colony in the late 1940s and early 1950s—all had commercial shows in London in the 50s. “But that interest, that support, petered out in the early 60s,” he says. “I think that is a consequence of the rise of Pop Art and colour field painting, whose internationalism was focused on New York. As London began to swing, it became more obsessed with itself, less global and, I think it’s fair to say, more white. I think a similar thing happened in Britain in the 1990s.”

Interest in Caribbean-British artists only really began to surge into the mainstream around 2016, the year the Black Lives Matter movement went global. “When my career took off in 2016, a lot of Caribbean descendant artists started getting a bit of a profile,” Forrester observes, pointing to the Guildhall Art Gallery’s 2015-16 exhibition, No Colour Bar: Black British Art in Action 1960-1990, as a pivotal moment.

Hurvin Anderson’s Jungle Garden (2020) is currently in a show of the artist’s work at Thomas Dane Gallery Photo: Ben Westoby; © Hurvin Anderson; Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery

The London dealer Thomas Dane agrees that in recent years “there’s been a redressing, and a very important one, of looking at people who had maybe not had the focus [from institutions and the market]”. This week, his gallery opened a show of recent paintings by Hurvin Anderson (Reverb, until 4 December) depicting an overgrown hotel complex in Jamaica, his parents’ homeland. It was Doig, quite the career maker, who suggested Dane should visit the artist’s studio 20 years ago: “He didn’t have a gallery, he was having to drive a van to earn money, so I sponsored him for six months so he could concentrate on his painting,” Dane says. He gave Anderson his first solo show in 2003 and has worked with him ever since.

Notably, Steve McQueen, the Oscar-winning filmmaker and artist who recently paid tribute to Britain’s Caribbean communities in the film series Small Axe, was Dane’s very first artist. “Hurvin and Steve are really the backbone of the gallery,” Dane says. “They both have a real sense of pride about their Caribbean heritage, but also about this country. I think that really shows in their work.”

With Tate’s telling of Caribbean-British art history billed as a “landmark group exhibition”, the question is whether it can reach a more diverse audience than the largely white and middle-class art-going public. “It’s up to Tate to do the outreach and to bring schools in,” Dane suggests. He hails the model of McQueen’s Year 3 project at Tate Britain, in which he displayed photographs of more than 75,000 children from London schools at the museum from late 2019 to early 2021. “It was about showing the extraordinary diversity of London and of Britain as a whole.”