This article is part of an ongoing series "Dispatches from Afghanistan" profiling Afghan artists and their experiences since the rise of the Taliban. Find all of the profiles so far here.

Mansoor has not been his usual fervent self since 15 August—the day that Kabul fell to the Taliban. He first spoke to The Art Newspaper on 14 August, when chaos was growing around the country and the Taliban were running amok where they had gained ground. A culture worker and arts enthusiast, Mansoor was hopeful despite the uncertainty, and he passionately discussed his work in arts and culture.

Mansoor and a few other like-minded young friends had opened a cultural centre with the dream of promoting the growth of the arts in their community and in the hopes of preserving Afghan culture, advancing their society and changing the conservative mindset they witnessed around them.

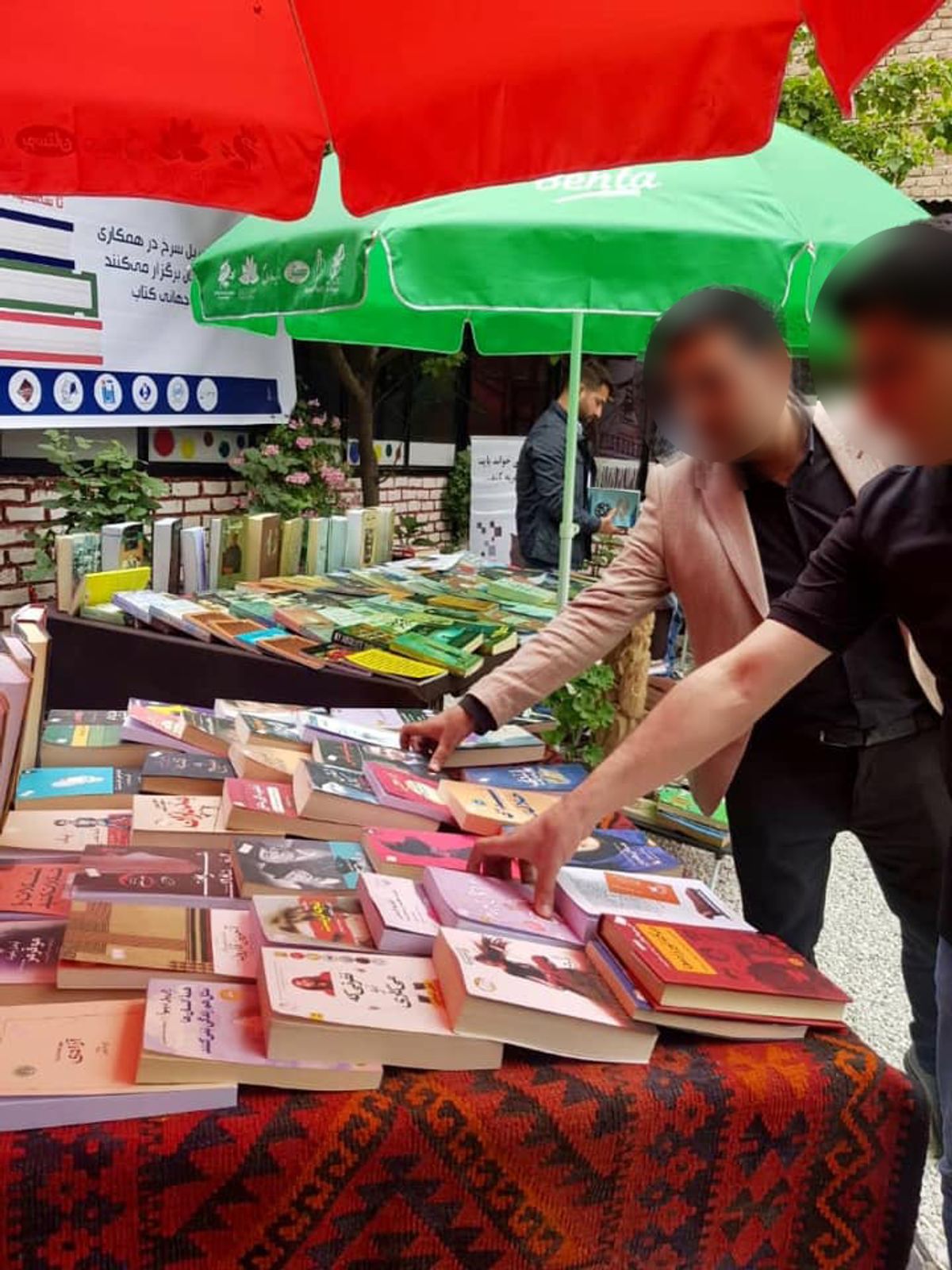

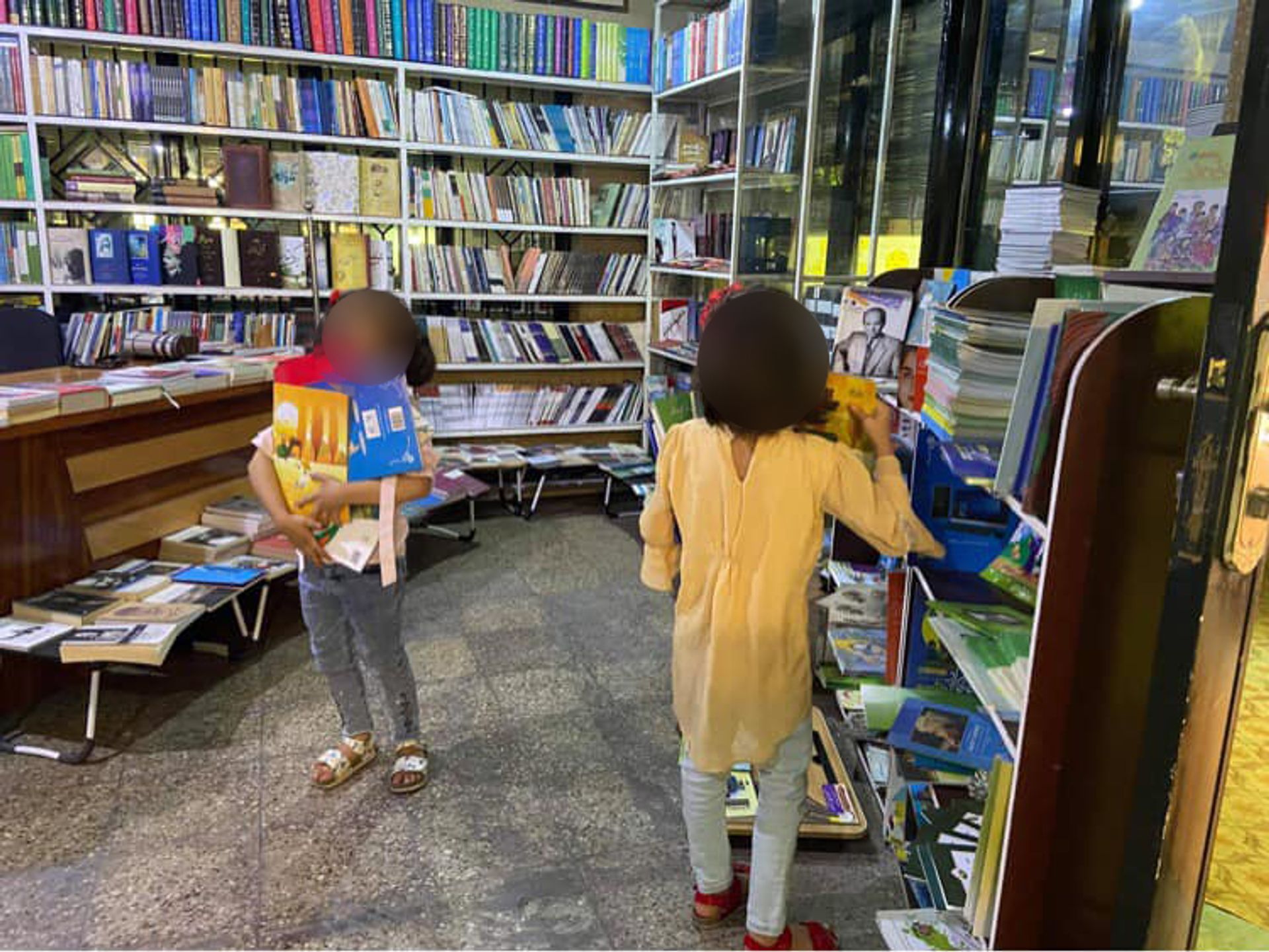

“We have achieved so much over the last few years. We have organised exhibitions, book festivals, music events, poetry sessions, arts classes,” Mansoor said exultantly at the time. He eagerly went into detail about how his group’s work ensured that books were made readily available to Afghans to encourage reading and about the music classes and events they had organised for people of all ages and backgrounds, boys and girls, despite the social pressures to not promote music. He was proud of the poetry sessions they held where they invited established poets and used their platform to tackle extremist ideologies; and of the art classes they conducted to help develop the raw and hidden talents of young Afghans.

Mansoor's events encouraged reading and music classes for people of all ages and backgrounds, boys and girls, despite social pressures Courtesy of Mansoor

Mansoor spoke briefly about his future if the Taliban did succeed in taking over the country which, less than 24 hours before the fall of Kabul, still seemed far-fetched. The then unlikely scenario made him nervous and he said it would make for a deadly future for him and others in his field. “I don’t know what we will do if the Taliban take over! I don’t think we will be able to continue with any of our work. It would be the end of us,” he admitted.

But Mansoor’s nightmares came true and he was left in shock when the inconceivable became a reality. “In Afghanistan, work in the field of arts and culture is probably one of the hardest jobs; from any angle that you look at it you will face many problems. Everyone who worked with us knew the challenges but we did it because we loved it. We accepted all the struggles and stuck with it in the face of declining security. We had finally reached a stage where we were established and recognised. But everything is destroyed and we are stuck,” a sombre Mansoor tells The Art Newspaper over a month after life as he knew it had ended.

In the two weeks that followed the Taliban takeover, terrified that he may be hunted by militants for his activities, Mansoor went to Kabul airport several times to see whether he could board one of the Western evacuation flights only to discover he did not qualify for the at risk priority groups. He had not worked with Western embassies or held any events with foreigners, one of the requirements of being considered at risk.

Mansoor has moved into an office with several other artists and cultural workers to minimise the risk of being attacked by the Taliban Courtesy of Mansoor

Familiar with the Taliban’s unforgiving ways towards those who criticised them, Mansoor and his friends immediately closed their art centre. They removed musical instruments, sculptures, paintings, pictures and any books or documents that the militants could find offensive and hid them. Mansoor took the decision to move his family to a separate location and moved into an office with several other artists and cultural workers. He says they stay together day and night, in groups of no less than five, to minimise the risk of being outnumbered and assaulted by the Taliban.

"We worked on so many important issues in this country: for democracy, for values, for culture, for civilisation, for modernisation. We wanted things to change here. But all of a sudden the country is in the hands of terrorists and we have been left with it."

When Mansoor reflects on his current situation he is still brimming with disbelief and dismay. However, what hurts him most is the feeling of being forgotten by everyone, especially the international art community, he says.

“We [artists and cultural workers] really did not expect that one day we would end up in this situation and that the world would turn its back on us. That artists around the world would leave us. That the world’s politicians would leave us. To not be a story anywhere in the world and for no one to speak about our misery anywhere. We expected that at least the artists from around the world would support us. We worked on so many important issues in this country: for democracy, for values, for culture, for civilisation, for modernisation. We wanted things to change here. But all of a sudden the country is in the hands of terrorists and we have been left with it,” Mansoor says.

Overnight, Mansoor and his team went from respected and recognised cultural figures in their city to taking shelter inside a small office, trying to figure out where their next meal would come from. They share what little food they can find during the day just to survive. With the banks closed and no income he has no way of paying his centre’s rent next month and has no hope for his future. “I really don’t know what will happen to us. There is nothing left for us here and we can’t go anywhere,” says Mansoor with a deep sigh.

• The cultural worker's name has been changed to protect his identity.

This article is part of an ongoing series "Dispatches from Afghanistan" profiling Afghan artists and their experiences since the rise of the Taliban. Find all of the profiles so far here.