• Read more about the opening of LUMA Arles here as well as other must-see art and culture spots in the city

The Art Newspaper: The Tower at LUMA Arles alludes to both the built and natural environments around Arles. Can you explain this synthesis in the building?

Frank Gehry: I responded sculpturally to the city. There are two important Roman structures that are close to LUMA Arles. It made sense to reinforce that aesthetic to create the entrance and foyer for the building as a drum. It was intuitive, responding sculpturally to what I saw in Arles, and then relating to it in some way.

Arles is surrounded by the Alpilles [mountain range] and that creates a strong image. When we talked with Maja Hoffmann [the founder and president of the LUMA Foundation] about capturing the light, it led to a naturalistic building up of the façade. It required something more related to the environment and the city of Arles.

Van Gogh famously said: “Those who don’t believe in the sun down here are truly blasphemous.” Not just the light; specifically, the sun was a talisman for him.

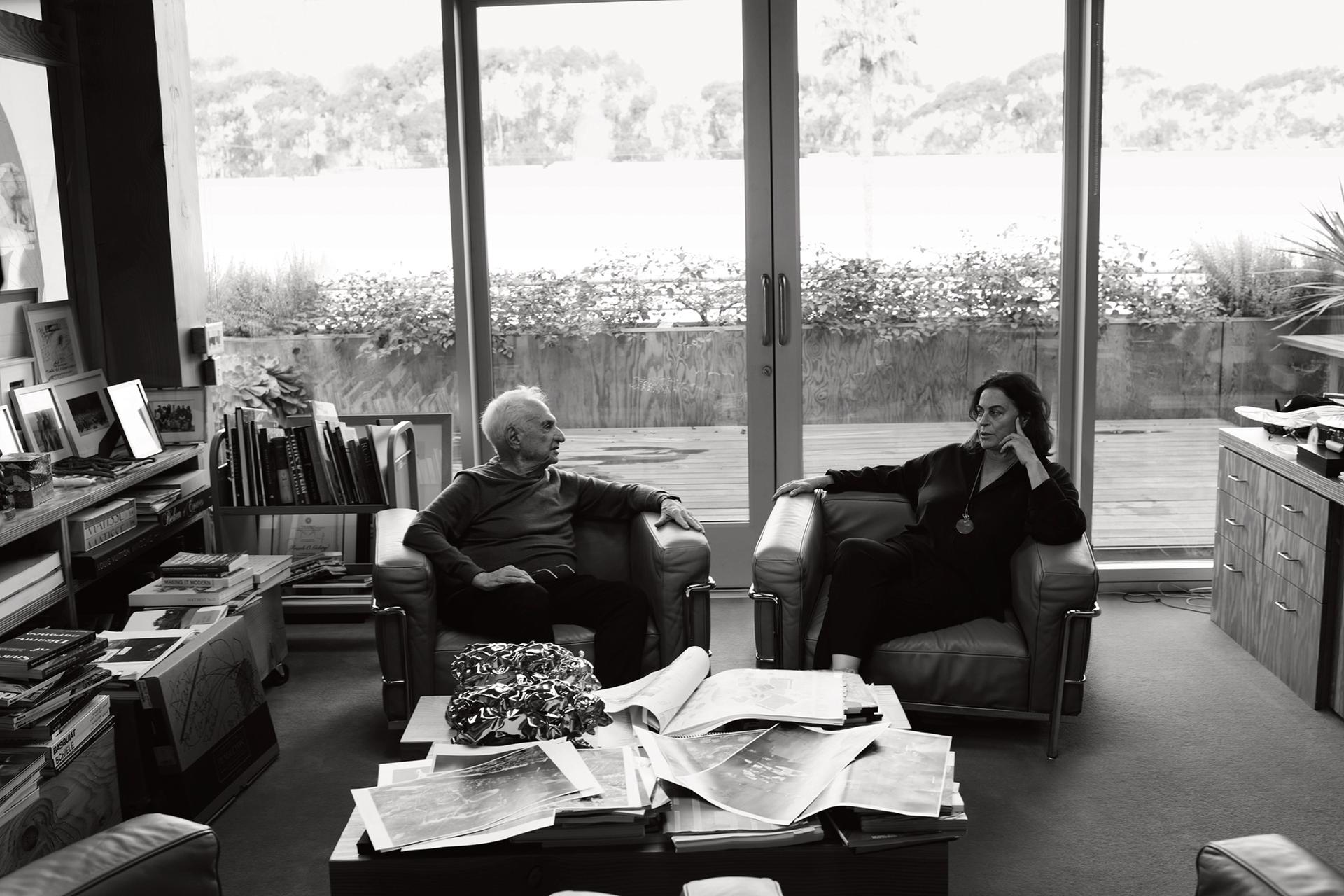

Frank Gehry and Maja Hoffmann in Los Angeles in 2019 © Annie Leibovitz

Was this a factor in your designs?

I think that my own art history and sense of Van Gogh’s presence in Arles was always in the back of my mind. I always kept thinking about what the light was like for him when he painted there. With the more naturalistic façade, we were able to make something that was not a single image but, rather, something that captured multiple images at different times of the day. I was excited by that, and I think we were successful. It changes all day and captures the light, and shows these different instances very proudly.

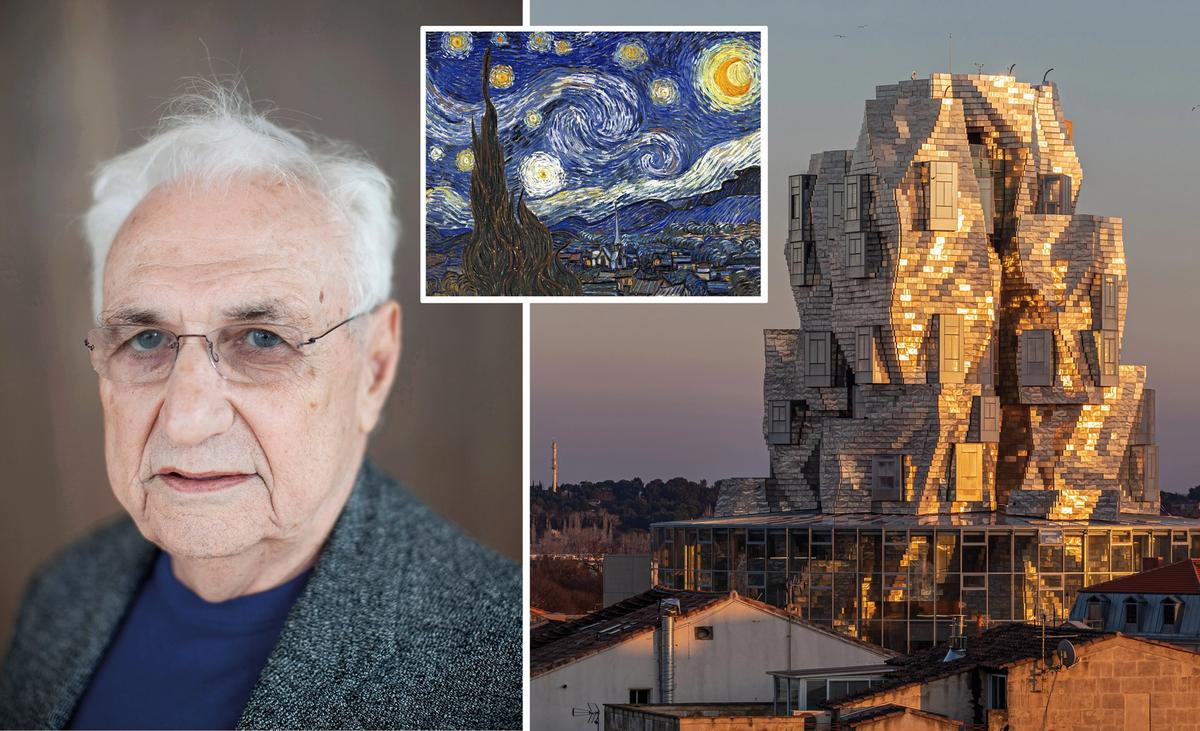

You’ve also said Van Gogh’s Starry Night was another influence. In what way?

Starry Night (1889) was painted in Arles and is an incredible painting we all love. I was curious what the light was like when he was painting and think that it must still be there today. The building in the evening does come close to capturing the colours of that painting.

Van Gogh's Starry Night was part of Frank Gehry's inspiration for his LUMA Arles tower

Given the reference to Van Gogh, and the evocation of his autonomous brushmarks in the tiles, might the building be described as painterly?

I think I have always been interested in how light hits buildings and in capturing a very painterly “brushstroke” in my buildings. The light is free, and it is part of the world that is always around us. Capturing it is taking advantage of an asset and taking advantage of something that is always changing.

Can you describe your approach to the materials for the building? The most eye-catching is obviously the stainless steel but, crucially, it is accompanied by the stone cuboid form and then glass and stone cylindrical base. It seems essential that there is an interplay between transparency and opacity, tangible and intangible effects.

The stone parts of the building were required to be solid—the archive, the storage, the elevators, mechanical areas and so on. I wanted to enclose all of those parts of the building that did not require light with large-scale blocks. It was difficult to achieve, so we used concrete so that it is a different scale from the metal and glass. The solid façades relate to the church and to the scale of the old stone buildings.

"It seems essential that there is an interplay between transparency and opacity, tangible and intangible effects," says Frank Gehry of his materials for LUMA Arles Photo: Adrian Deweerdt / LUMA Arles

The building has multiple uses. Can you explain how you have catered for its range of activities?

The project was designed with maximum flexibility in mind, albeit within the context of a tower. Early on during the programming phases, LUMA’s core group of advisers informed us that contemporary notions of exhibition spaces should be expanded beyond the white-cube spaces that typically define spaces for art. The artists and curators wanted to challenge conventional ideas of how art and architecture engage with each other. We established early on that there would be spaces that could satisfy traditional gallery requirements, but the majority would invite and compel the artists to engage them.

The initial programme for the building defined it as a space for the research, production, display, education and archiving of art in conjunction with other disciplines. Therefore, the spaces were designed to function with multiple uses in mind. Classrooms could also be galleries, libraries could be exhibition spaces, and exhibition spaces could be used for events.

An aerial view of the LUMA Arles site in September 2020 © Hervé Hôte

This programmatic flexibility was enabled in much of the spaces by flexible lighting systems that could suit both the stringent criteria of gallery lighting while offering the comfortable illumination of everyday situations; climate-control systems that could adapt to various occupancy scenarios and museum preservation climate requirements; daylight control to efficiently achieve blackout conditions when required, while taking advantage of the sunlight in Arles when natural light was desirable; and acoustic treatments on ceilings and walls to satisfy the varying conditions that might arise.

Around The Tower are 19th-century former industrial buildings revitalised by Annabelle Selldorf. She has spoken about her work as “anchoring the site” alongside The Tower. What kind of correspondence have you had with Selldorf and the landscape architect, Bas Smets?

We had meetings with Annabelle, which were very collaborative, and we understood her assignment and respected her solutions. They are very strong and compelling. I think it was collaborative in a sense, but all the collaborative work was intelligently managed by Maja—as well as working with Bas, who is likewise talented.

At 56m, The Tower is one metre lower than the bell tower of Arles’s tallest historic building, the Cordeliers Convent, now Saint-Charles High School. Is this a coincidence? Was this a condition of the planning authorities or your own form of deference to historic Arles?

The height was never referenced to an existing structure. The 56m height was calculated based on view studies from Les Alyscamps—the Unesco World Heritage Site adjacent to our former building location. The ideas guiding the allowable height were determined by the ABF [Les architectes des bâtiments de France, the body that oversees historic French heritage] to minimise the visibility from the Romanesque church. Due to the archaeological sensitivity of a buried Roman necropolis, our original building proposal was rejected on the former site; however, the maximum allowable height that was determined for this location was transferred to the current site.

• Read more about the opening of LUMA Arles here as well as other must-see art and culture spots in the city