“O Almighty God, be so kind, tell me: did you create my Agulis or did my Agulis create you?”. Thus were Agulis and its eight majestic churches serenaded by the Nobel Peace Prize-nominated Muslim Azerbaijani author Akram Aylisli, who now lives under house arrest for writing a novel on the glory and gore of that magical place.

Nestled in the far south-western foothills of the former Soviet Union, in Azerbaijan’s exclave of Nakhichevan, Agulis was already a depressed village when Aylisli was born in 1937, at the height of the Stalinist Terror. Yet centuries prior, it had been the most culturally and economically vibrant small town of that key contact region straddling Europe and Asia—the Caucasus.

For more than 2,000 years, the indigenous Armenian population of Agulis and the wider canton of Goghtn (Azerbaijan’s present-day Ordubad district) created a unique culture, including folk poetry recorded as early as the fifth century that influenced the 20th-century composers Aram Khachaturian and Komitas, both of whom traced their ancestry in that region. Goghtn’s Armenian existence was terminated in the past century—first during the First World War-era Armenian Genocide, then in a complete physical erasure of all cultural remnants, following centuries of miraculous survival.

Armenian women of Agulis Photograph: Dmitri Yermakov (Argam Ayvazyan historical archive)

“If a single candle were lit for every Armenian killed violently,” Aylisli reflected in his banned novel Stone Dreams, which references 1,500 years of conquest, occupation and erasure, “the radiance of those candles would be brighter than the light of the moon.” Aylisli’s own mother, a righteous Muslim Azerbaijani resident of Agulis (Aylis in Azerbaijani) witnessed the massacre on 24-25 December 1919, when Ottoman troops, aided by local Azerbaijani opportunists, brutally killed the entire Armenian community. The Agulis Massacre formed part of Ottoman Turkey’s 1915-23 campaign known as the Armenian Genocide, in which an estimated 1.5 million Armenians perished, as well as many Assyrians, Pontic Greeks and Yazidis.

Akram Aylisli in Agulis Image: courtesy of Katherine E. Young

Despite learning of his hometown’s trauma from a young age, Aylisli fell in love with its striking polychrome mountains exalted by the majestic medieval churches built by Armenians. “Each church was the exact same colour as the mountain next to it,” Aylisli wrote of the eight surviving Christian houses of worship of Agulis (several others had been destroyed during and after the 1919 Agulis Massacre), built in organic architecture “as if it had been cut out whole from the mountain and placed there, where it was easy and comfortable for God to contemplate it”.

While Aylisli describes remote Agulis as a lost paradise, it was not an isolated place. Beginning with the “Treaty of Peace and Frontiers” of 1639, the Middle East’s rival Muslim empires entered an eight-decade period of relative stability. It was during this time that the cross-continental Armenian merchants of Agulis became key players in the Silk Trade, traversing Safavid Iran, Ottoman Turkey, Russia and Europe. They brought back wealth and ideas to harmonise nature, heritage and modernity. They renovated and built a dozen majestic churches, 17 spring water qanat fountains, schools, libraries, a hundred artisan shops, and textile factories. They planted lavish orchards bursting with lemons, olives, apples, nuts, quinces, mulberry and grapes. The latter, according to the early medieval historian Movses Khorenatsi, were a key ingredient—in the form of wine—for the lyrical creations of Goghtn.

A wedding party in Agulis in the 19th century; in December 1919, Agulis’s Armenian community was eradicated as part of Ottoman Turkey’s campaign, known as the Armenian Genocide, which killed around 1.5 million people Photograph: Mesrop Papazian (Argam Ayvazyan historical archive)

When Stone Dreams was published in 2012, it evoked nostalgia for many who had seen or heard of the splendour of Agulis. After all, the town had become only a distant memory. Since the dissolution of the USSR, the government of post-Soviet Azerbaijan has forbidden any Armenian person, regardless of citizenship or profession, from visiting Agulis. But for the Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev, the novel was apparently a nightmare. Seemingly overnight, Aylisli’s standing in his country went from hero to villain, all at the whim of the politician. Aliyev revoked Aylisli’s pension and title of “People’s Writer”. His writings were erased from school curricula. He was banned from travelling. His family members were fired from their jobs. His books were publicly burned.

Tovma’s interior, photographed by the researcher Argam Ayvazyan after he convinced locals to open it Image: Argam Ayvazyan archives 1964-87

Violent erasure

Until Stone Dreams, Aylisli had been Azerbaijan’s most famous author, a revered figure, his books translated into more than 30 languages. Nevertheless, in the eyes of the president, the 2012 book committed the gravest of sins: “deliberate distortion” of history, a particular fixation of Azerbaijan’s authoritarian leader. To him, the history communicated by Aylisli was nothing more than “fake news”.

From 1997 to 2006, Aylisli witnessed the violent erasure of historical traces that President Aliyev deemed unfit for existence. The successive Aliyev presidents, father and son Heydar and Ilham, along with their loyal relative and local satrap Vasif Talibov, engaged in the covert destruction of Nakhichevan’s entire indigenous Armenian-Christian heritage. This included 89 churches, 5,840 cross-stones, and more than 22,000 tombstones, an estimate based on independent researcher Argam Ayvazyan’s documentation from 1964-87.

Azerbaijani officials now say that the Armenian monuments of Nakhichevan never existed at all, despite having previously labelled them, erroneously, as “Caucasian Albanian”, in reference to a long-extinct people. After a decade-long investigation, this erasure was exposed by this writer in Hyperallergic in 2019. The Guardian rated the exposé “rock solid”; a top Azerbaijani diplomat, on the other hand, called the research “a figment of Armenia’s imagination”.

But the timeline of the destruction of the estimated 28,000 monuments can be reconstructed with precision. Aylisli sent a telegram to his country’s president, which was published in English for the first time in the 2019 investigation. “Honorable Mr. President,” wrote Aylisli to President Heydar Aliyev on 10 June 1997. “Recently it became known to me that in my native village of Aylis large-scale work is underway [by the military] for the eradication of Armenian churches and cemeteries...” Aylisli concluded with “hope that urgent measures will be undertaken on your part for ending this evil vandalism”.

Painting of the churches of Agulis by Lusik Aguletsi, the last Armenian of Agulis, whom Akram Aylisli recalls in Stone Dreams as a young artist

International outrage

Aylisli’s telegram did not end the destruction, but international outrage halted—albeit temporarily—its most high-profile target, the cemetery of Djulfa on Iran’s border. In 2003, after Ilham Aliyev replaced his deceased father, a former KGB leader-turned-president, he started pumping oil to Western markets through new pipelines. Emboldened yet struggling with domestic legitimacy and frustration over the unresolved Nagorno-Karabakh conflict (which in the early 1990s had displaced nearly a million people, a majority of whom were Azerbaijanis, and reduced the Azerbaijani cities of Agdam, Fizuli and Jabrayil to ghost towns), Ilham Aliyev began stoking anti-Armenian sentiment to boost his nationalist credentials.

On 6 December 2005, Talibov, the de facto ruler of the Nakhichevan republic, issued public decree No. 5-03/S, instructing an investigation and inventory of all local monuments as “the seal of Azerbaijanism of this ancient land”. Days later, Azerbaijani army platoons—caught on tape from across the border in north Iran by Bishop Nshan Topouzian—were deployed to Djulfa (in Armenian, Jugha) to finish off the destruction of the world’s largest medieval Armenian cemetery that housed several thousand khachkars (cross stones). The government of Azerbaijan has denied that the vandalism happened, stating that Armenians never lived in Nakhichevan.

In 2008, the findings of the investigation were detailed in the bilingual (English and Azerbaijani) Encyclopedia of Nakhchivan Monuments, co-edited by Talibov himself, with a foreword that concluded that all of the region’s monuments had been demonstrated to “belong to Azerbaijani Turks” despite “Armenians’… biased information”.

Talibov’s encyclopedia listed zero Armenian monuments; yet even the multi-volume Azerbaijani Soviet Encyclopedia, which typically downplayed Armenian history, had noted the churches of Agulis. Two years after Talibov published his encyclopedia, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, in collaboration with this writer, issued its very first investigation into cultural destruction, documenting the total erasure of Djulfa. The satellite investigation was necessitated by Azerbaijan’s prohibition of international access to the crime scene.

Today, the “Kuwait on the Caspian” continues to deny Agulis’s Armenian past and persecutes Aylisli for admiring its antiquity, acknowledging its pain and condemning its erasure. It also bans researchers from exploring the town. In 2013, the independent Russian journalist Shura Burtin managed to briefly sneak in, just long enough to see that no churches or cemeteries were left.

Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh

“The most difficult thing is to learn to lie. But as soon as you learn, everything goes forward smoothly,” wrote Akram Aylisli in 2018, as he contemplated hate crime perpetration and denial in his recently-penned essay Farewell, Aylis.

As the post-Soviet flattening of Armenian heritage in the Nakhichevan region comes into view through declassified Cold War satellite imagery—affirming Aylisli’s eyewitness account—new threats seem to loom. Following the November 2020 ceasefire to the Second Nagorno-Karabakh war, approximately 1,000 antique and medieval Armenian cultural sites are now under Azerbaijan’s control. To say that these sacred heritage sites are at risk might be a monumental understatement.

The president of Azerbaijan states that Armenians are not indigenous to Nagorno-Karabakh, while mirroring charges of cultural genocide by accusing Armenians of wiping out mosques. Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenian sacred sites face a grave risk, not least because Azerbaijani officials continue to deny Nakhichevan’s erasure by declaring that Armenians never existed there.

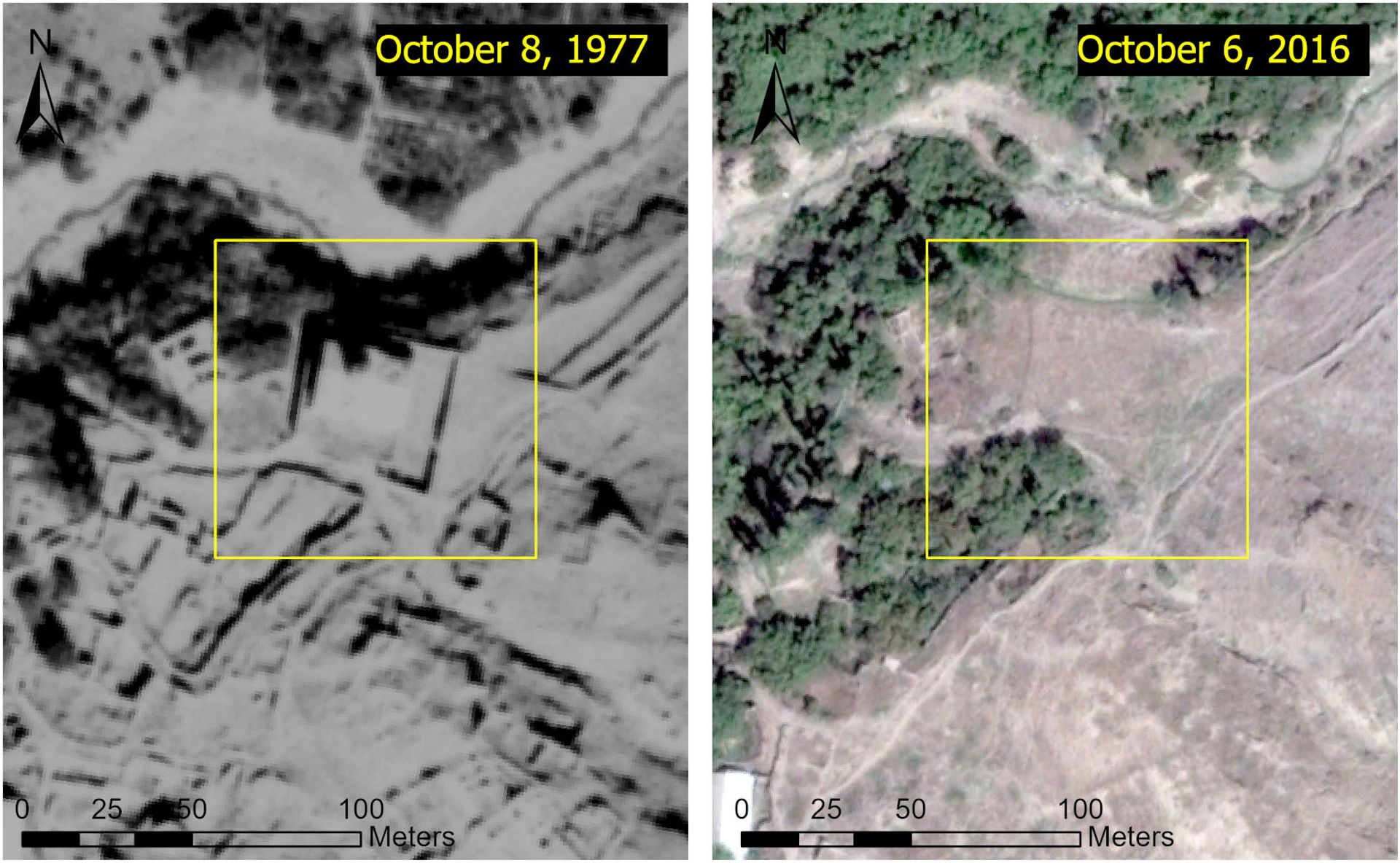

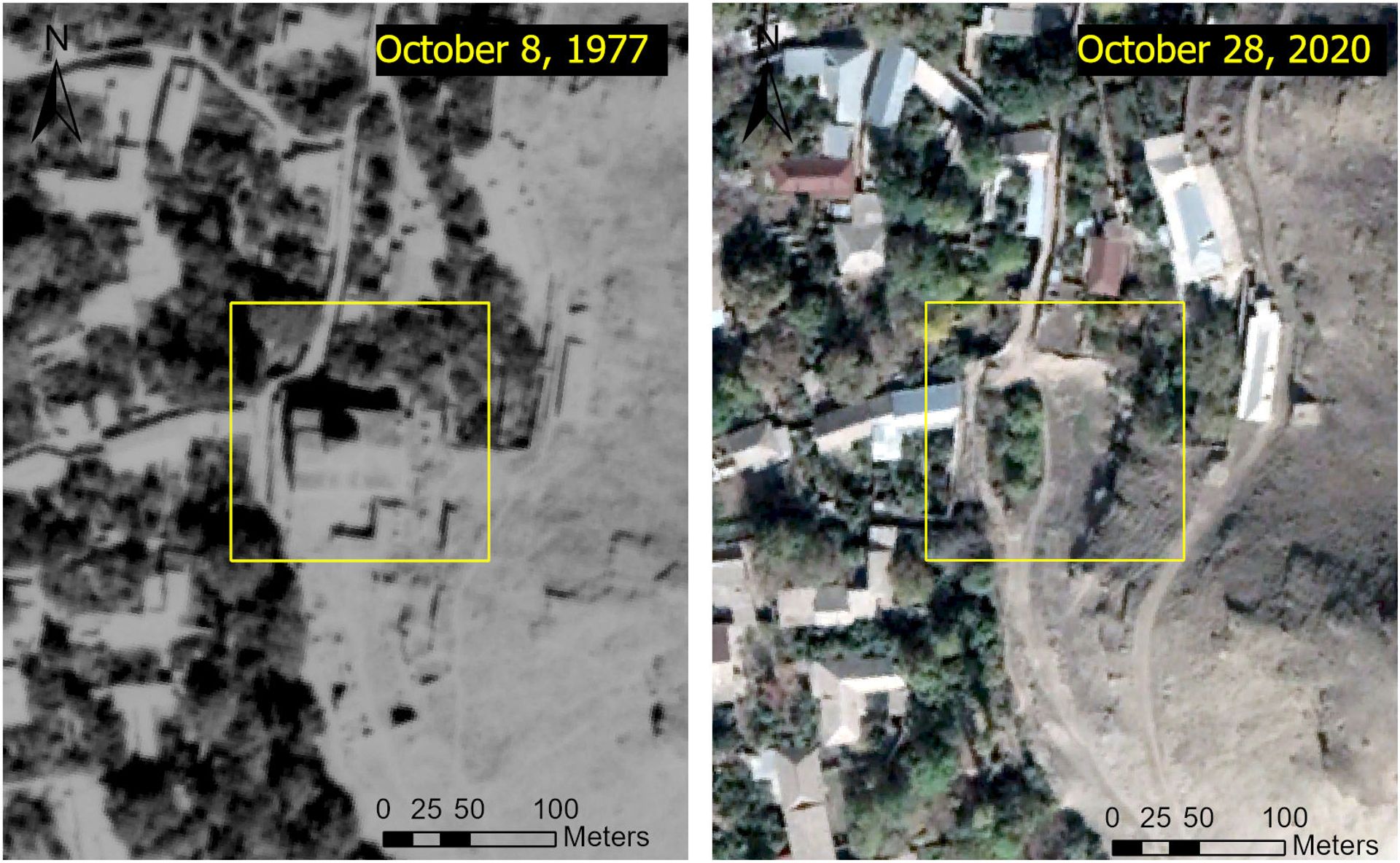

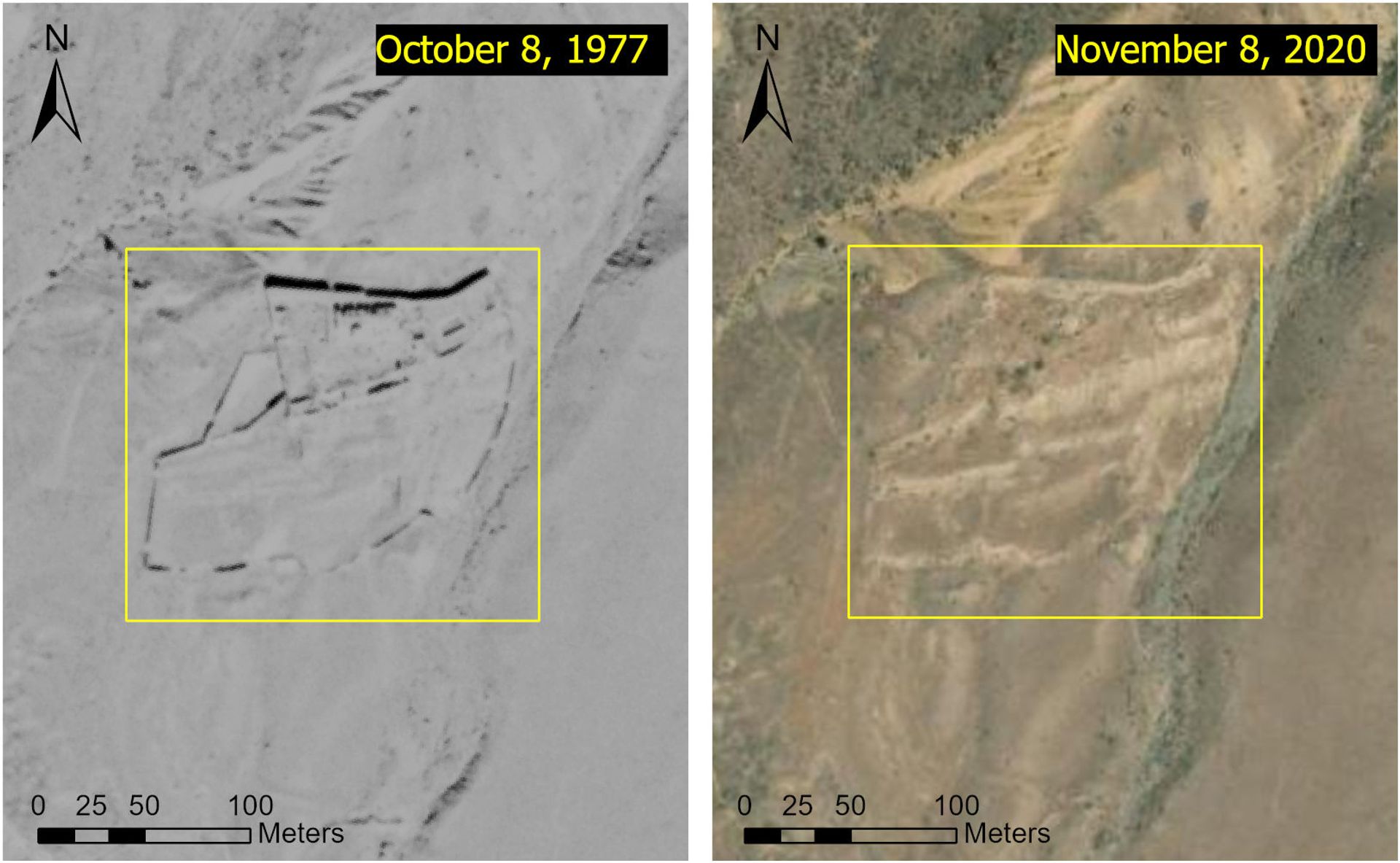

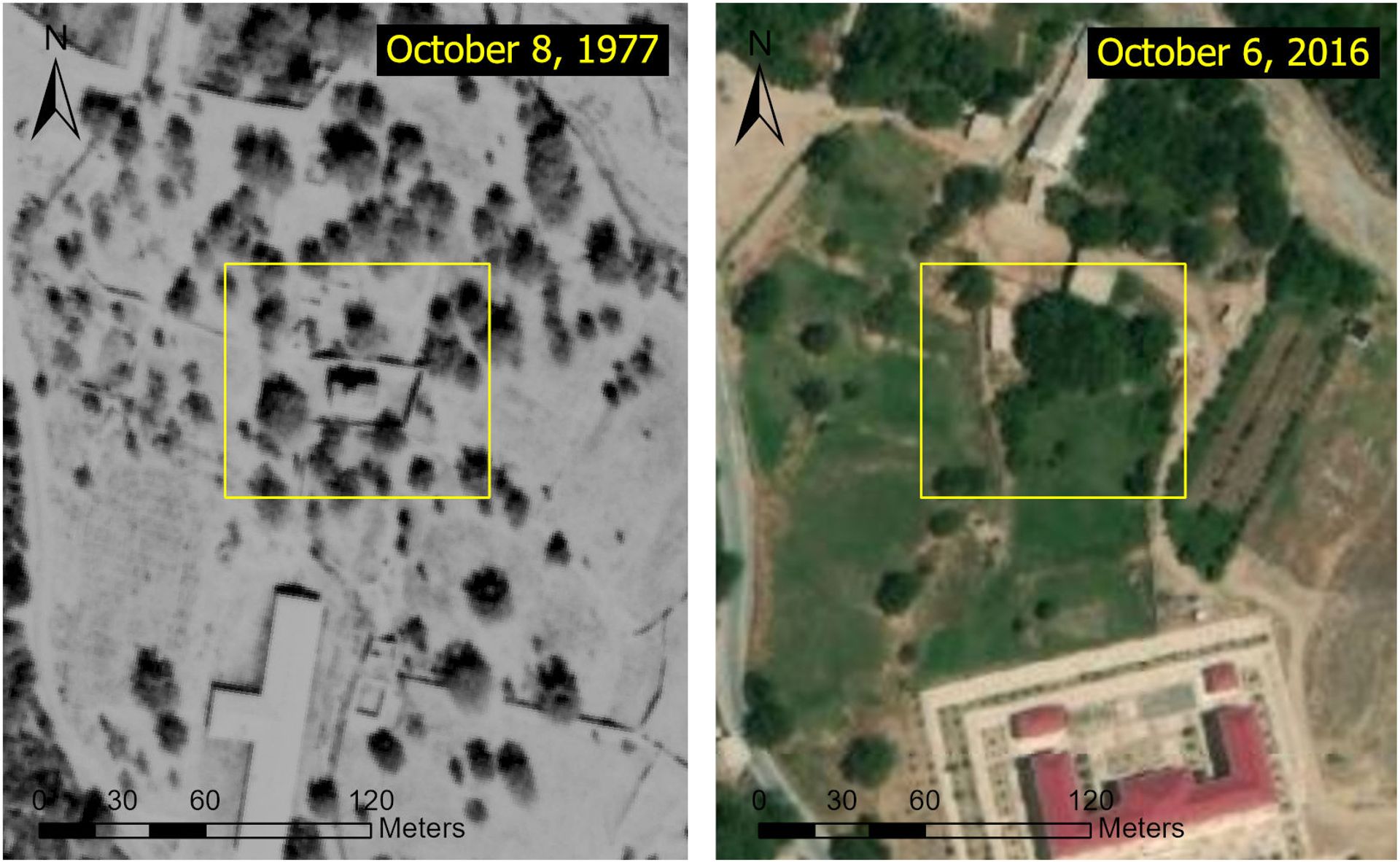

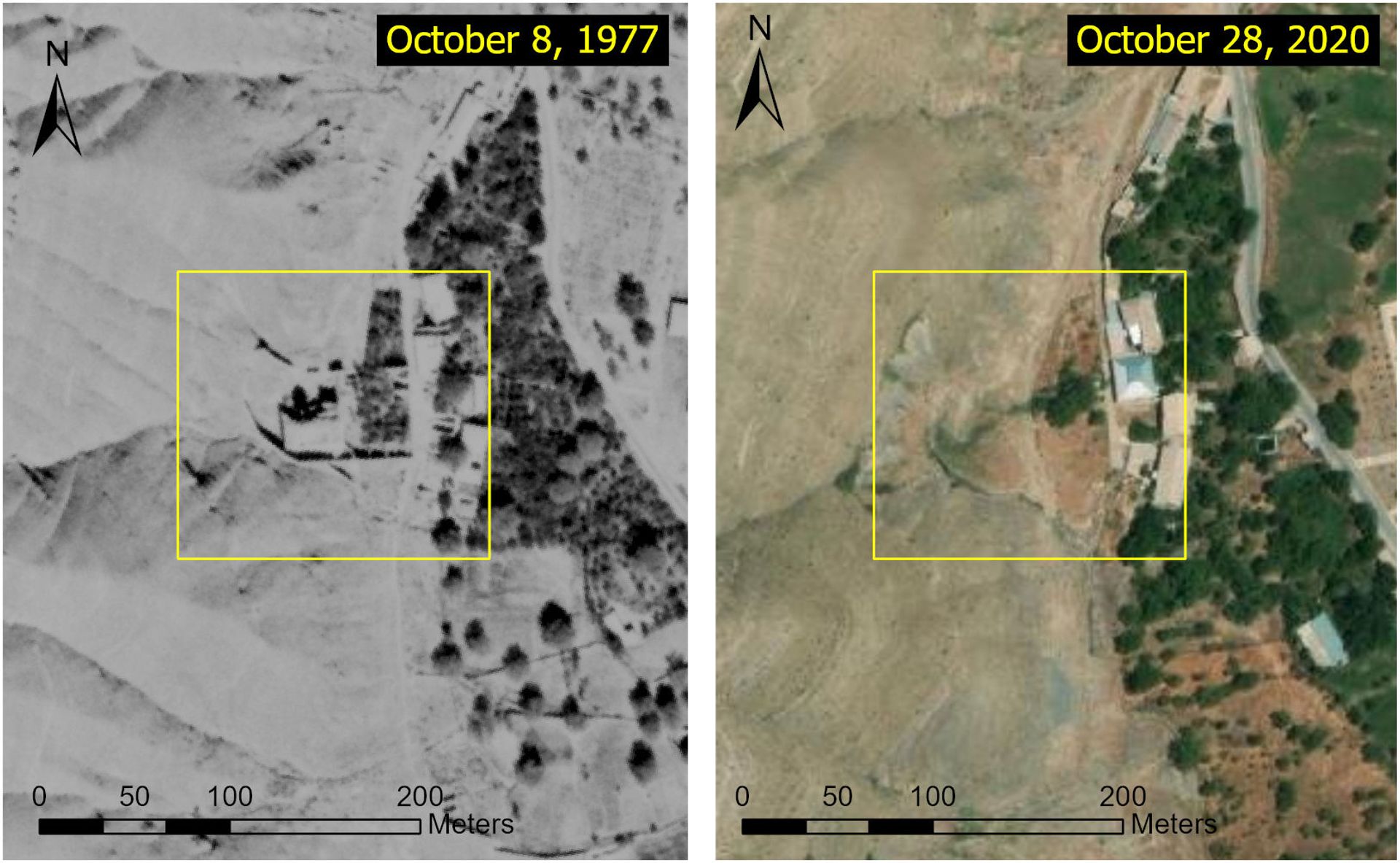

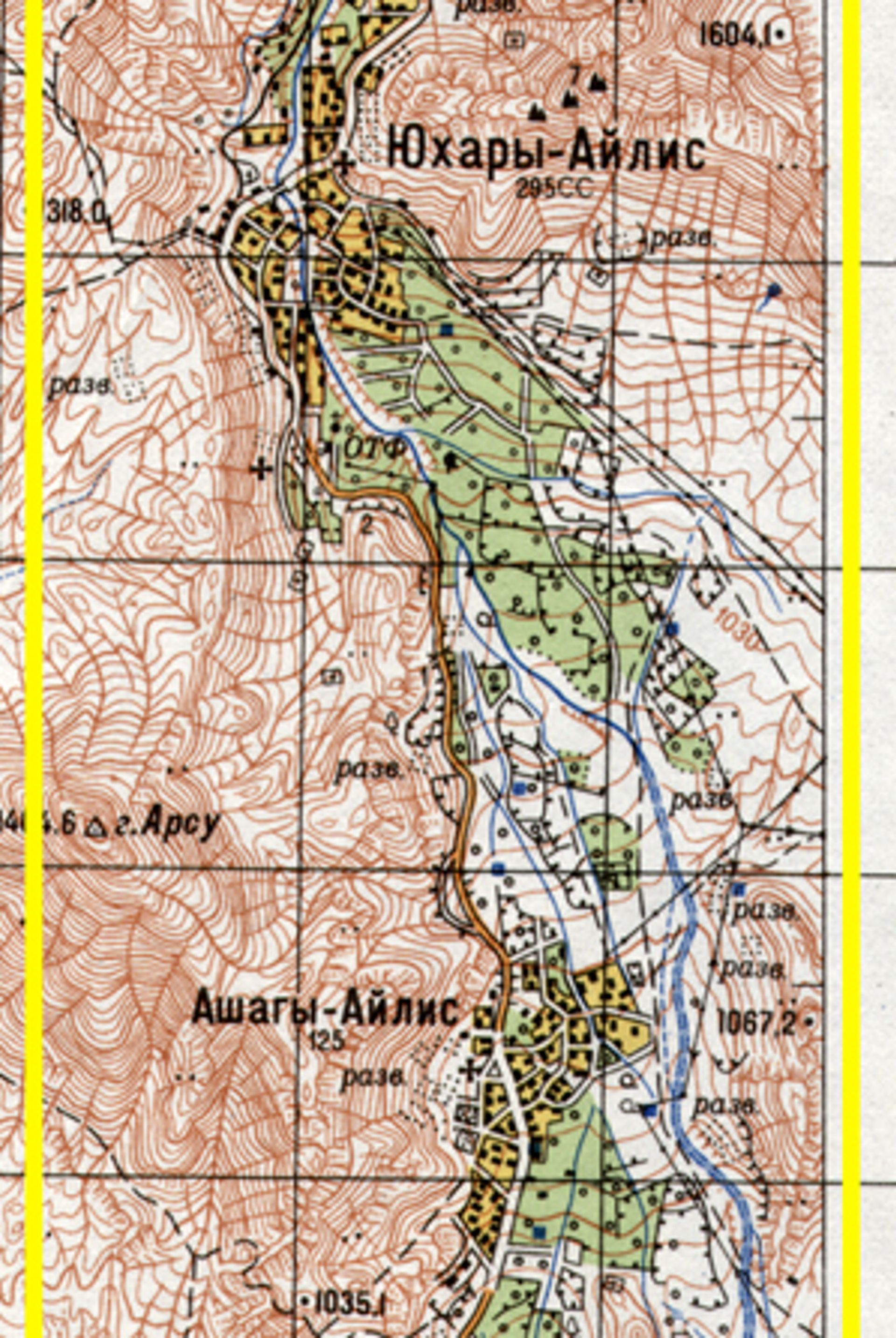

While magical Agulis is forever gone, recently declassified materials offer help in reconstructing its erased historical landscape. A rare positive side-effect of the Cold War was the mutual clandestine map-making and satellite imagery collection activities by the US and the USSR. Thanks to these, the precise locations as well as discernible images of the major churches of Agulis have been preserved. All are from the 1970s, including two maps produced by the USSR General Staff’s Office that list all the major churches, and geospatial imagery produced by the US’s declassified spy satellite programmes.

These before-and-after satellite images are published for the first time.

Stepanos

Image: KH-9 Hexagon and Google Earth satellite imagery analysed by Caucasus Heritage Watch and Simon Maghakyan

Agulis’s northernmost church, Surb Stepanos (Saint Stephen), was, according to Ayvazyan, likely founded in the 12th to 13th centuries. It was rebuilt in the 17th century, during a church construction boom in eastern Armenia, then under the control of Safavid Iran, and renovated in 1845 and again in the early 20th century. The satellite image shows the fortified church and the shadow cast by its dome, which are absent from the new satellite imagery.

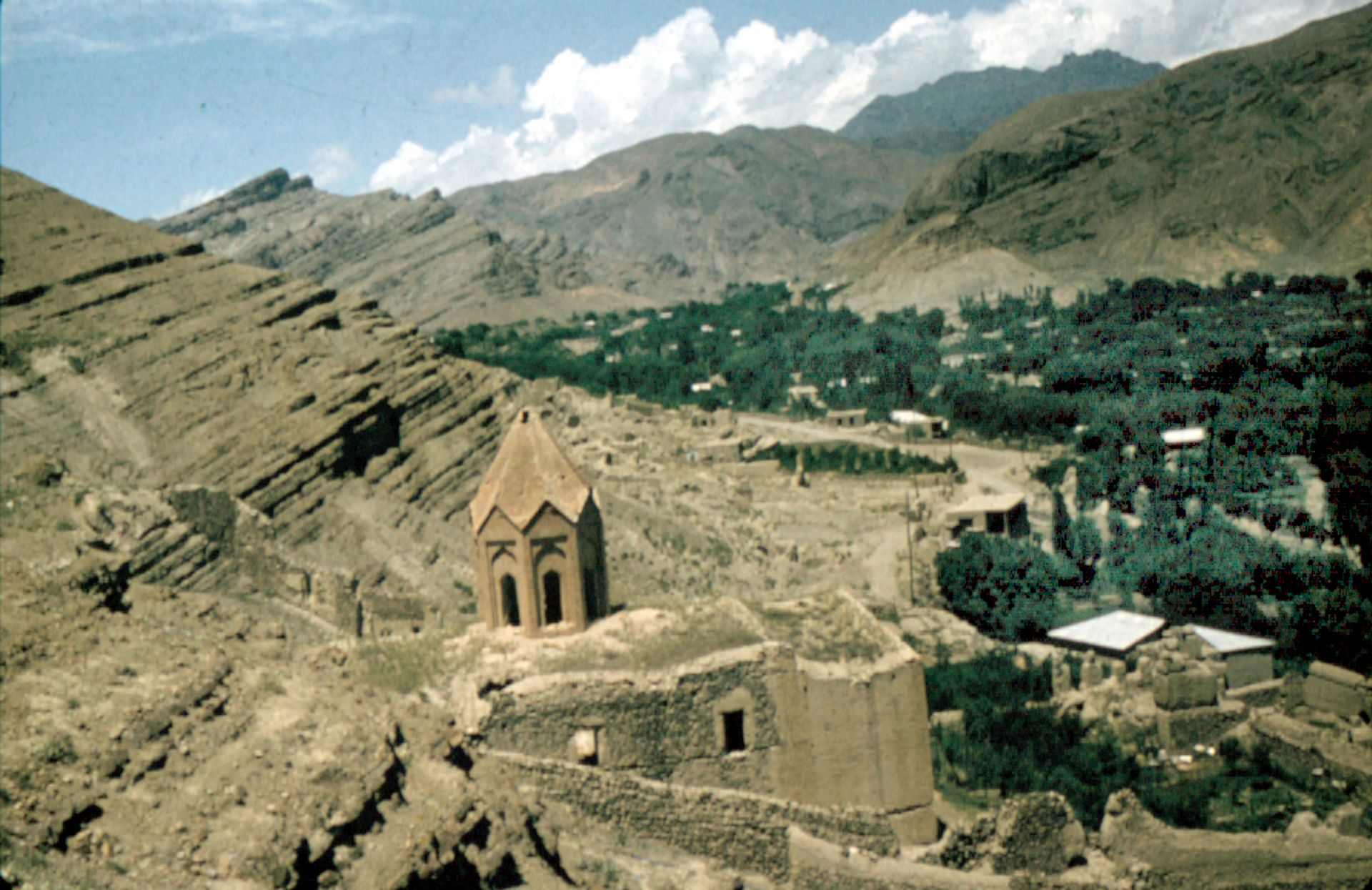

Tovma

Image: KH-9 Hexagon and Google Earth satellite imagery analysed by Caucasus Heritage Watch and Simon Maghakyan

Surb Tovma (Saint Thomas) was one of the largest and most important monastic complexes of medieval Armenia. A survivor of the 1919 Agulis Massacre recounted in his memoir that “this sanctuary surpasses all the Armenian churches and monasteries I have ever seen in its magnificence and, particularly, interior beauty”.

The fortified complex featured numerous structures, including an outdoor altar that local folklore claimed to have been a pre-fourth-century pagan temple. The inscription above the ornate door, added during a late-17th century expansion, recounted a folk tradition that dated the sacred site to the first century: “Bartholomew [the Apostle] came to Armenia and first founded the Lord’s house here. He named the place after the Apostle Saint Thomas and established an episcopal throne, on which he placed his disciple Komsi as the overseer of this land, which is the district of Goghtn. He turned over to him the chosen flock near Agulis and its renowned plain.”

Satellite images show the complete disappearance of Tovma, followed by a later construction of a mosque. According to Aylisli, Muslim Azerbaijanis boycott the new structure since “prayers offered in a mosque built in the place of a church don’t reach the ears of Allah”.

Early 20th-century photograph of Tovma in the foreground of Agulis Courtesy of the History Museum of Armenia

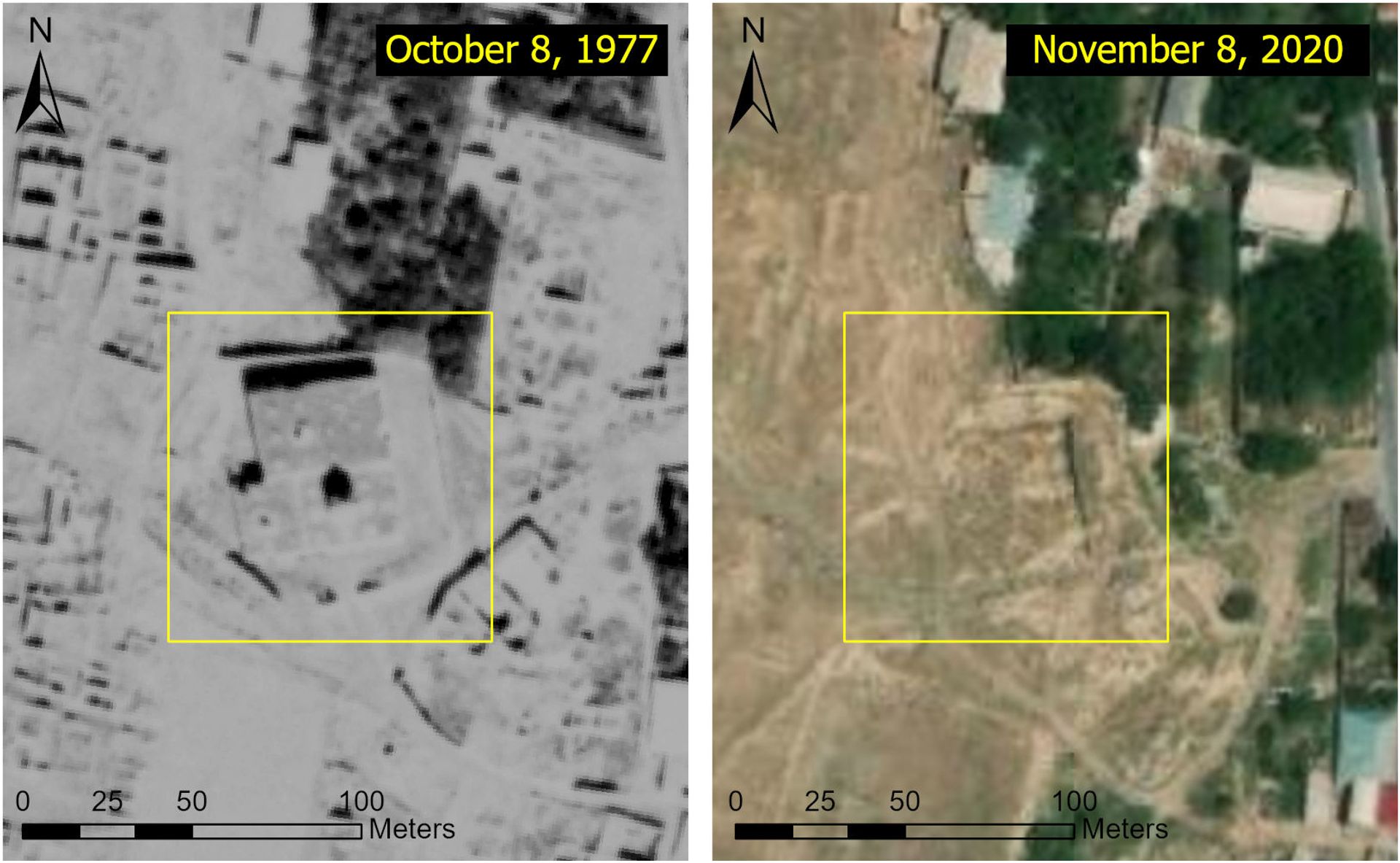

Kristapor

Image: KH-9 Hexagon and Google Earth satellite imagery analysed by Caucasus Heritage Watch and Simon Maghakyan

Situated in a prime central location of Agulis, across the bridge from the famed bazaar (now destroyed), Surb Kristapor (Saint Christopher), per local folklore, was founded in the first century by the Apostle Jude Thaddeus. The merchant Zakaria of Agulis recounted the rebuilding of the church in the 1670s, for which he served as a patron, and the addition of a sealed donation box “with a European lock” in 1680.

Like nearby Tovma, Kristapor displayed 17th-century frescoes by the celebrated artist Naghash Hovnatan, who also painted the Holy See of Etchmiadzin, the centre of the Armenian Church. In the late 19th century, the church established a school for girls. A photograph of Kristapor adorns the dust cover of Aylisli’s trilogy Farewell, Aylis, translated by Katherine E. Young. Satellite images show the church’s complete disappearance.

A historic image of Surb Kristapor © Argam Ayvazyan Archives

Mets Astvatsatsin

Image: KH-9 Hexagon and Google Earth satellite imagery analysed by Caucasus Heritage Watch and Simon Maghakyan

Described by Aylisli as the “Mecca and Medina for Armenians”, Mets Anapat Surb Astvatsatsin (Greater Hermitage Holy Mother of God) was a large complex resting on the hills of Agulis, 1.5km to the east of the town. The fortified monastery included a dozen structures, in addition to the church, vineyard, fountain and graveyards. In the 1980s, Ayvazyan surveyed 97 tombstones at Mets Astvatsatsin, 46 of which displayed inscriptions. The site is believed to have originally been a pagan shrine, predating the adoption of Christianity in AD301, reinforced by the reported discovery of clay and metal pagan statuettes during an 1874 renovation that were immediately destroyed by two religious zealots.

Mets Astvatsatsin was a well-known destination for late-medieval Armenian pilgrims, especially for the August holiday of the Assumption of Holy Mother of God. Likely due to its rocky terrain, the outline of the foundations can still be seen in the post-destruction satellite imagery, suggesting that the remote site’s total erasure may have posed a monumental challenge to the Azerbaijani military.

A historic image of Mets Astvatsatsin © Argam Ayvazyan Archives

Hakob Hayrapet

Image: KH-9 Hexagon and Google Earth satellite imagery analysed by Caucasus Heritage Watch and Simon Maghakyan

Rebuilt in the 17th century and renovated in 1901, Surb Hakob Hayrapet (Saint Jacob of Nisibis) was the smallest of Agulis’s surviving churches. The USSR General Staff maps identify the church as a Christian monument, instead of a regular church. The imagery attests to its complete disappearance.

Hovhannes

Image: KH-9 Hexagon and Google Earth satellite imagery analysed by Caucasus Heritage Watch and Simon Maghakyan

Renovated in the 17th century, Surb Hovhannes Mkrtich (Saint John the Baptist) was one of the main churches of Agulis. It was also famous for being the burial grounds of Priest Andreas, who in 1617 prevented the sexual enslavement of Armenian schoolchildren during the visit of the Persian Shah Abbas by shaving their heads to make them appear unattractive. For that, the furious Shah had the priest tortured and executed.

In 1922, a survivor of the Agulis Massacre visited Hovhannes, recounting that “its dome and belfry had been destroyed, and the door removed. The church had been thoroughly plundered and then pulled down. Its yard and two large gardens had been totally devastated, just like the houses and other gardens adjoining it.” Satellite imagery shows the church largely intact, before its complete disappearance in subsequent images.

Surb Hovhannes Mkrtich © Argam Ayvazyan Archives

Amarayin

Image: KH-9 Hexagon and Google Earth satellite imagery analysed by Caucasus Heritage Watch and Simon Maghakyan

The two adjoining churches of lower Agulis, one of which is a domeless basilica, are known by a variety of names. It appears that additional historical Armenian remains, including house ruins, around the Amarayin complex have also been destroyed.

Cemeteries and historical ruins throughout Agulis

1977 USSR General Staff map section pinpointing the churches, cemeteries, and ruins of Agulis

The USSR General Staff map pinpoints half-a-dozen cemeteries and many more ruins. Due to substantial challenges involved with identifying medieval cemeteries (combined, Agulis had approximately 2,000 historical tombstones, many of which were photographed and sketched by Ayvazyan in the 1970s and 1980s), we refrained from identifying the cemeteries or other ruins, including the large remnants of Surb Shmavon (Saint Simon the Zealot) church.

• Simon Maghakyan is a visiting scholar at Tufts University, Massachusetts, and a lecturer at the University of Colorado Denver.

DISCLOSURE NOTE: This report was supported by an Armenian General Benevolent Union grant. The declassified Cold War materials were acquired and analysed with help from the scholars Argam Ayvazyan, Lori Khatchadourian and Adam T. Smith, as well as the Yerevan-based non-profit organisation Research on Armenian Architecture.

Response from Tahir Taghizade, Ambassador of Azerbaijan in the UK

“First and foremost, we need to make it clear that there is no such thing as ‘Armenian heritage’ in the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic simply because Armenians never lived there. Primary academic research on the history of the region would testify to this. Non-existing sites or cemeteries cannot be destroyed.

“Armenia’s claims for ‘Armenian heritage’ in Nakhchivan is nothing more than an effort to support their—yet another—territorial claim against Azerbaijan using fake propaganda and ungrounded allegations. This is also to divert the world’s attention from cultural genocide that Armenia, in blatant violation of the relevant international norms, including the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict and its Protocols, have committed in Azerbaijan’s Nagorno Karabakh and seven adjacent regions during their occupation by Armenian forces (1992-2020).

“More than 400 monuments, religious sites and other cultural objects were totally destroyed, demolished and desecrated by Armenia to annihilate any sign of cultural presence of Azerbaijan in these territories. Major cities like Aghdam, Fizuli, Jabrayil, Zangilan, Gubadli, Lachin, Kalbajar were razed to the ground. Out of 67 mosques and Islamic religious shrines, 64 have been destroyed or significantly damaged and desecrated. More than 900 Muslim graveyards, and tombs and shrines were ruined. Now that Azerbaijan liberated these territories, vast evidence is available verifying the scale of vandalism committed by Armenia.

“Regretfully, our appeals to the relevant international organisations to investigate war crimes including the deliberate destruction, misappropriation, alteration of our cultural heritage, as well as illicit removal of our cultural properties by Armenia have been ignored throughout the 30-year occupation. We welcome the interest now being shown in this respect.”