Check out The Art Newspaper's guide to London Gallery Weekend for recommendations on the best exhibitions to see during the three-day event, top trends and commentary

Jade Montserrat, Untitled (The Wretched of the Earth, after Frantz Fanon) (2018) Photo by Constance Mensh for the Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia

In December 2017, the artist Jade Montserrat posted a picture on her Instagram account, a selfie sent to her by her former patron Anthony d’Offay, one of the most high-profile figures in the British art world. Nearly ten years earlier, d’Offay had part-sold and part-gifted an extraordinary collection of contemporary art to Tate in London and the National Galleries of Scotland.

For this largesse, d’Offay was hailed as an extraordinarily generous benefactor. But the image posted by Monsterrat, which showed the retired dealer and collector peering into a mirror while holding a golliwog, led to allegations that there was another side to his character.

After Montserrat published the golliwog image, three other women who had worked for d’Offay came forward with accusations of sexual harassment which were published in the Observer newspaper in January 2018. Their accusations are strongly denied by d’Offay, who said he was “appalled” that they were being levelled against him.

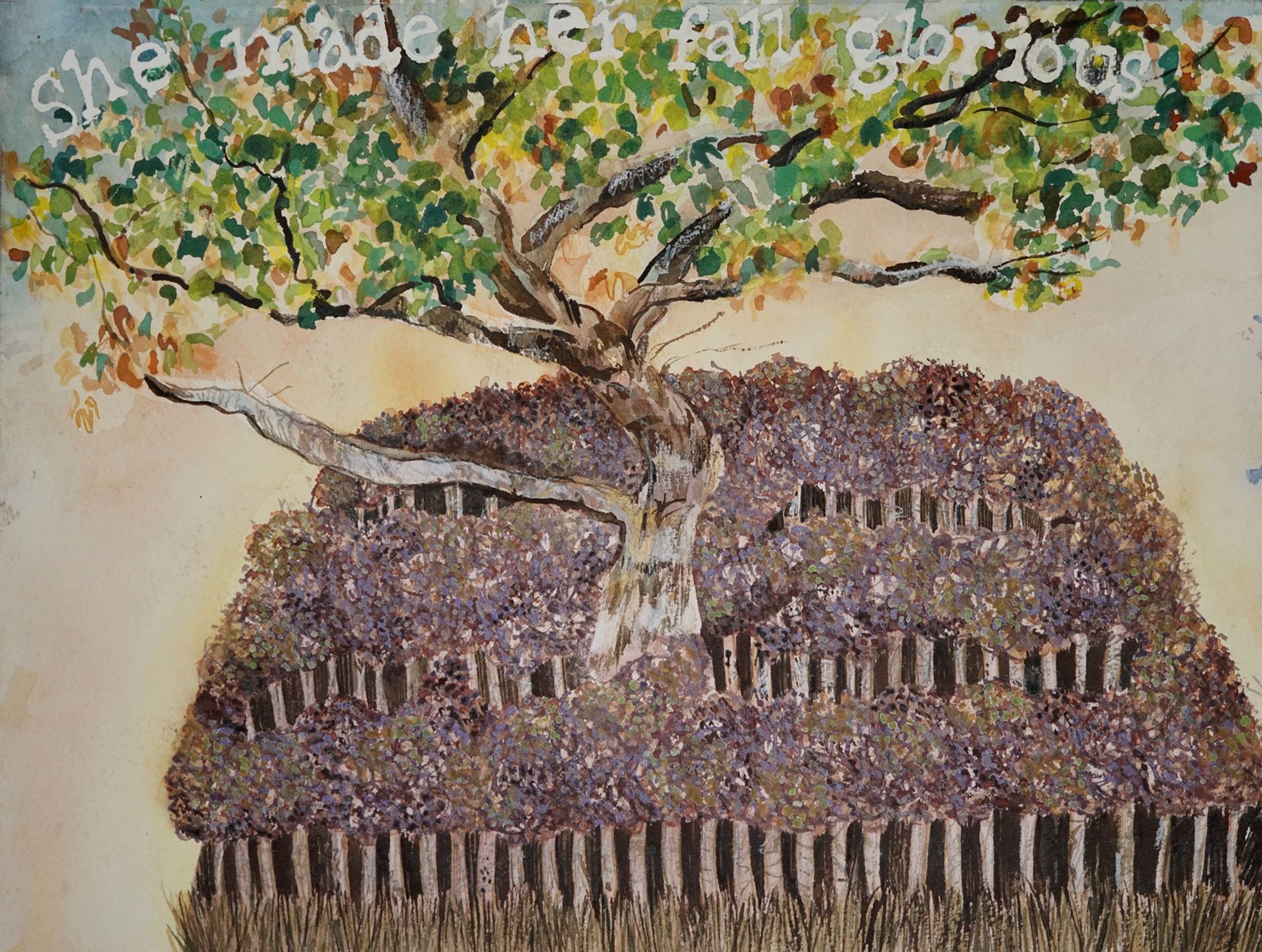

Jade Montserrat, She made her fall glorious (2016) Courtesy of the artist and Bosse & Baum

The controversy which ensued eventually led to Tate severing its ties with the art patron over two-and-a-half years later; returning to him works of art which he had loaned to the institution and removing his name from the museum. This followed pressure from activist groups such as Industria who took up Montserrat’s cause and called for Tate to apologise to her for not responding to her repeated attempts to engage the gallery in dialogue about d’Offay.

“It has been an incredibly stressful time,” Montserrat says of the past few years. After all, it takes a brave emerging artist to take on publicly not just d’Offay but also Tate, one of the most influential museums in the world. But if Montserrat started her fight alone and isolated, through her activism and her art she has found a community of like-minded peers. “Now, I’m working with people who recognise one another’s strengths…it’s not about anyone exploiting anyone else; it feels like there’s always room for growth which is the opposite of what I initially experienced in the art world,” she says.

Most recently, solidarity for Montserrat has come from the artist collective Black Obsidian Sound System (B.O.S.S.) who published a statement just days after being nominated by Tate for the Turner Prize. In this, they highlight Montserrat’s experiences with the museum, among other issues. “How can a BPOC queer collective of artists and cultural workers be nominated for the [prize] whilst Black women artists continue to be silenced?”, they asked.

Montserrat was “moved” by and “grateful” for B.O.S.S’s statement. “Their demonstration of collectivity in this widest sense has energised my spirit. I trust it signals to others that supporting one another is what it’s about. This is what it looks like and brings comfort to others who feel alone in complaint, we are in it together…Thank you,” she wrote on Instagram when reposting the group’s statement.

Jade Montserrat at CAS (Chapel Art Studios) in 2019 © Jade Montserrat

Looking forward

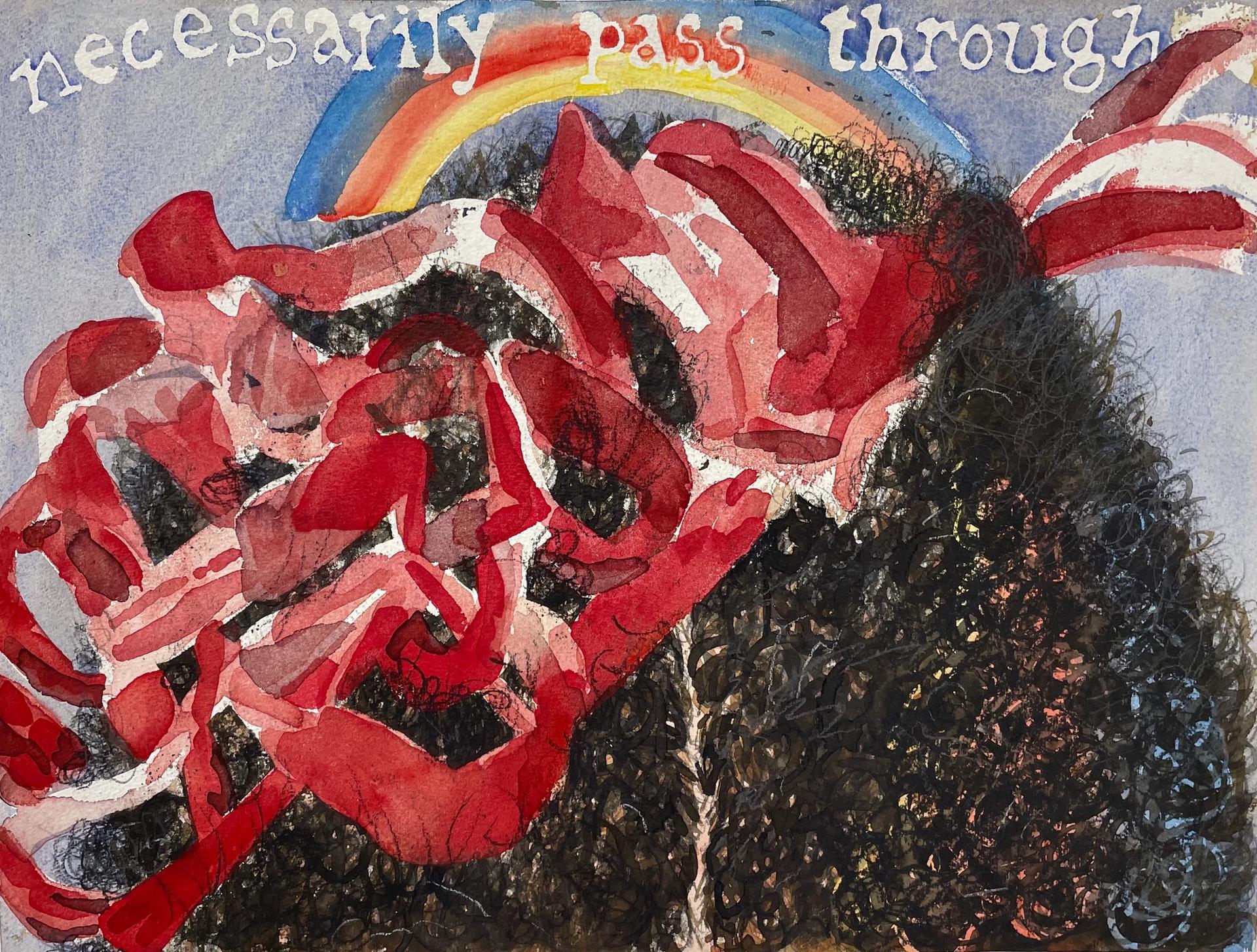

Now, Montserrat is looking forward to her first solo show in a commercial gallery, In Search of our Mothers' Gardens, which opens on 5 June at Bosse & Baum in Peckham, as part of London Gallery Weekend. On display are around 30 watercolours and works on paper priced under £3,500, including depictions of nature which explore “our connection to the earth,” Montserrat says, as well as works on paper from a series she has made based on a photograph of her own torso. Each torso has been embellished by Montserrat, some with intricate African hairstyles, recalling the idea of enslaved women braiding native seeds into their hair before being forced onto transatlantic slave ships, others with decorations reminiscent of the gilded tunics of Catholic saints, “my mum is a lapsed Catholic,” she explains, and Montserrat herself was christened as a Catholic.

The exhibition takes its title from a 1972 essay by the American novelist Alice Walker in which she recounts the journey to the Southern United States of the poet Jean Toomer in the 1920s and his recollections of the Black women he met there, “so abused and mutilated in body, so dimmed and confused by pain, that they considered themselves unworthy even of hope…toiling away their lives in an era, a century, that did not acknowledge them, except as ‘the mule of the world.’” Montserrat has grappled with the meaning and implications of this essay “for years”, she says.

Jade Montserrat, Torso, Notre Dame D’Afrique (2016) Courtesy the artist and Bosse & Baum

She stages performances in which she is often naked, for example, as she writes poetic texts which explore racist histories on to the walls of galleries and museums in black charcoal. The early inspiration for Montserrat’s nudity came from the Black entertainer and French resistance agent, Josephine Baker, who performed a Danse Sauvage at the Folies Bergère in Paris wearing nothing but a string of artificial bananas slung low around her hips. “My nudity is about reclaiming Black labour and also my Black body and sexuality for myself,” Montserrat says. “Of course, you can be quite vulnerable when you’re naked, but you’re also incredibly powerful,” she says.

These racist and colonial histories are woven throughout Montserrat’s work. She delights, for example, in taking long walks with her dog in the landscapes surrounding her home in rural Yorkshire, but she is also interested in unravelling our collective relationship with nature and examining how this replicates the racism and prejudices of society at large. “Nature is sensual and gives us great relief but it’s also a place to locate our shared histories,” she says. “I’m reading about the origin of Britain’s flora, for example, and the author describes in quite heroic language, the ‘warriors, explorers and plant hunters’ who brought foreign plants to Britain; she doesn’t say ‘actually, these people were colonists who oppressed indigenous populations,” so that’s an interesting choice.”

Despite the dark stories that run through her work, there is also a lot of joy and celebration. One watercolour on display at Bosse & Baum shows a Black woman, face obscured, running her hands through her massive Afro which takes up most of the composition. “This was about me trying to capture that feeling of not being able to comb my hair, so I have to run my hands through it instead, which is an incredible feeling,” she says. The figure is framed by a dark, starry night which creates the impression of a Black goddess shaking the stars out of her hair. “Yes, it’s like a myth about how the stars were created,” Montserrat says. The word “simply” floats at the top of the work, a reference, Montserrat says to the simplicity of the gesture of running hands through hair, which “feels good; it’s simple self care,” she says.

Jade Montserrat, Simply (2016) Courtesy the artist and Bosse & Baum

Art and activism

Speaking to The Art Newspaper on zoom from her home between the seaside towns of Whitby and Scarborough, Montserrat says she is “exhausted” by the toll her activism has taken on her. She’s been calling for change her entire life, she says. Growing up Black with a white mother and white stepfather in rural Yorkshire in the 1980s was a profoundly isolating experience. “My immediate family were xenophobic and they were proud of it. There were only a few people of colour in our local community; there was a Black man who clearly had learning difficulties but he would walk around town and every time I saw him, I would think ‘is he my dad? The only other person I thought might be my father was Eddie Murphy because we had a video shop nearby so I watched a lot of movies growing up.”

At school, Montserrat turned to her teachers for support but they “were not equipped to deal with anyone different,” and she was labelled “difficult” early on. “Instead of anyone asking me ‘what do you think these feelings are?’, they just moved me from school to school.” Finally, she was sent away to boarding school, aged only seven, an experience she describes as “terrifying.”

Today, she is determined to stay in Yorkshire, partly because she loves the landscape but mostly because it is her home. “I grew up here, have lived here my whole life. Why should I leave?” She has spent the last year making art; as well as the upcoming Bosse & Baum show she has work in a group show currently at Lisson Gallery and also has a solo project at Manchester Art Gallery where she has been invited to interact with works from the museum’s historic collection and to make new art which will be acquired by the gallery. She is also helping to support young artists. “I’ve done a lot of tutorials and workshops this past year,” through the Ruskin School of Art where she serves as a dissertation tutor on the MFA programme, and others. “It’s so important that we pass on what we have learned to younger artists and support one another,” she says.

Jade Montserrat, Necessarily pass through (2016) Courtesy the artist and Bosse & Baum

• Jade Montserrat: In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens, 5 June-24 July, Bosse & Baum, Unit BGC, Bussey Building, 133 Rye Lane, SE15 4ST

• An Infinity of Traces, until 6 June, Lisson Gallery, 27 Bell Street, NW1 5BY

• Constellations: Care & Resistance, until 31 October, Manchester Art Gallery

Check out The Art Newspaper's guide to London Gallery Weekend for recommendations on the best exhibitions to see during the three-day event, top trends and commentary

Click here for the full list of galleries taking part in London Gallery Weekend

The Art Newspaper is an official media partner of London Gallery Weekend