“I remember sitting on a terrace in Nice with my uncle and an old friend of his, both in their eighties. They started discussing the meaning of life, firing one saying, anecdote and reflection after another, like a machine gun, in many languages”.

That cosmopolitan, philosophical but worldly-wise way of being is what formed the art dealer Johnny Eskenazi, born in 1949 in Italy into a secular Sephardic Jewish family of Ottoman origin, with business interests from Austria and Italy to the UK.

“It was very warm and secure. There was an army of relations who would arrive from all over the world. We mainly spoke French and Italian at home, but English with my father, who had been an Intelligence officer in the British army during the war.”

Eskenazi grew up in an Italy that was modernising and developing as fast as China today. The family art gallery, founded in 1925 and specialising in Chinese and European porcelain and carpets, was in Milan. His education was chaotic, from a French kindergarten to a state school (where for the first time he heard the words “dirty Jew”), then an international school, where his best friend was an Iraqi who ate raw onions for lunch; finally, a US school, from which three of his contemporaries went on to die in Vietnam. After a year in London, he returned to an Italy transformed by the 1968 revolution—anarchic, at times violent, but creative and idealistic.

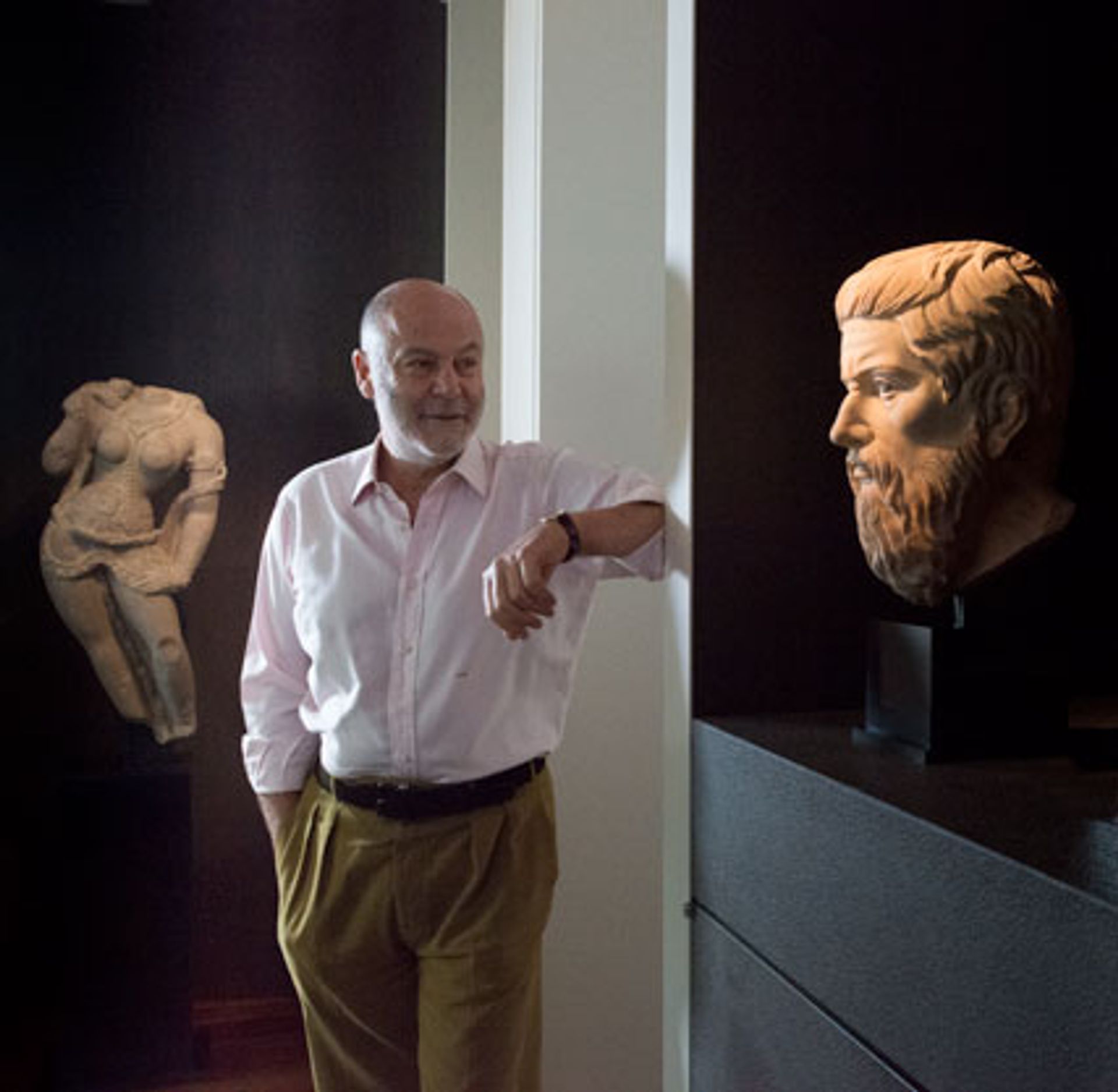

Johnny Eskenazi

A very rigid history of art course at university palled, so he abandoned it for a degree in stage design at the Accademia di Brera in Milan. The theatre became a passion and he worked with the city's Piccolo Teatro. “I dreamt of being apprenticed to Peter Brook and becoming a director, but my father needed me in the gallery,” he says.

But the call of the East was also strong and he went on long backpacking journeys through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, the Himalayas and India: “It was safe then if you knew how to behave. I felt in perfect harmony with myself when I was there; while in Milan, people were convinced that I had become a drugged-out hippy,” he says. It was on these journeys that he came into contact with a spirituality that has influenced him for the rest of his life, without, however, tempting him to adopt any of the region's religions, which, he says, would feel like putting on fancy dress.

The Hare Krishnas and the Milanese elite rub shoulders in the family gallery

When he was about 26, Eskenazi began work in earnest and put on one exhibition after another in the gallery, exposing the Milanese to Indian and Himalayan art they had never seen before. His 1977 show of Buddhist and Hindu Tantric art, the first in Italy, was gate-crashed by the Hare Krishna followers, tinkling their cymbals and bowing in front of the objects.

Unlike his father, who was a connoisseur but not a scholar, study has been as important to Eskenazi as dealing, as can be seen from the quality of his gallery catalogues. In 1988, he published his big book, Il Tappeto Orientale (Allemandi), now in its eighth edition, which he wrote because he felt a need to sort out the confusion in the field. [Declaration of interest: the book came out with Umberto Allemandi, in whose publishing house he was a shareholder until The Art Newspaper was sold in 2013.]

But his kind of art did not speak to Italian taste. While there have been great Italian collectors of carpets, he says, the sculpture of the East does not appeal “except in a decorative kitsch way”, and almost no museum was interested.

Surrounded by other gallery owners and the rich Milanese, Eskenazi always felt on the sidelines, he says, freely admitting that this might make him seem a snob. So finally, in 1994, he left Milan for London, the deciding factor being the rise to power of Silvio Berlusconi, with his “stupid fascism”. The attraction of Britain was its cosmopolitanism; the mutually respectful relationship between curators, academics and dealers; and a much wider market, which included the US curators who arrived regularly on buying trips.

Why Eskenazi's gallery of religious sculpture from the Indian sub-continent became a mecca for curators

It is no exaggeration to say that Eskenazi's gallery, above Colnaghi’s in Old Bond Street, was an instant sensation. The combination of its elegance; Eskenazi’s capacity to be both easy in manner and highly knowledgeable; and the spectacular sculptural works in the 1995 inaugural exhibition Images of Faith: Buddhist Art, and thereafter, made his gallery an obligatory stop for curators and collectors over the next 15 years or so. Eskenazi has sold to over 40 institutions, he says, from the British Museum to the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore. Eighteen of these are in the US, a market he carefully cultivated by visiting them one by one—for Eskenazi is nothing if not a good businessman.

Eskenazi also understood that collaboration makes one stronger, so, in 1997, with Michael Spink, he set up Asia Art Week for the Asian art galleries in London, and then also in New York, followed in 2004 by London Sculpture Week. Eskenazi’s reputation as a scholar is such that he has been able to cross the dealer/curator line, as with his exhibition on the court arts of Safavid Iran at the Asia Society in New York and the Museo Poldi Pezzoli and Palazzo Reale in Milan (2003-04) and the show of Chola bronzes at the Royal Academy of Arts in London (RA) in 2007.

Why did museums want to buy from Eskenazi in the 1990s and 2010s? The reasons, as always in the history of taste and the art market, are complex: a growing economic and political awareness of the world beyond the West; rich collectors who in their hippy years may have dabbled in oriental religions; masterpieces of Western art becoming harder to find; and some outstanding scholars such as Pratapaditya Pal making Eastern art intellectually exciting. Last, but not least, contemporary art had yet to become a mainstream obsession and investment opportunity.

The Unesco Convention and how museums have almost stopped collecting in the field of antiquities

Today museums have almost stopped collecting in Eskenazi's field and there are few new private collectors. The Unesco Convention against illicit trafficking had been in existence since 1970, but it was not until the later 2010s that museums began to look askance at any antiquity that did not have a documented provenance from before that date.

A watershed event was the indictment of the Getty Museum curator of antiquities Marion True by the Italian government in 2005 on charges of acquiring trafficked works of art. This sent up a red flag to US museum lawyers and the previous basis on which US museums bought, which was that an item was innocent unless proven guilty, changed to “all items are guilty unless proven innocent”. The change in the legal climate was compounded by the Afghan and the Middle East wars, particularly the Second Iraq War (2003-11), with the comprehensive looting by Iraqis of their own National Museum in Baghdad, and then the iconoclasm and looting by Isis.

Since then, Unesco has made the issue of looted antiquities into a major campaign and this has considerably reduced the desirability of all antiquities, even though the organisation has been shown to grossly inflate estimates of the size of the market in looted goods, and last month made the embarrassing gaffe of including items from the Metropolitan Museum of impeccable provenance in ads warning against collecting looted works.

Eskenazi has resigned himself to a dwindling market although he still sells to a few museums and private collectors, dedicates himself to research, sponsors symposia and books in his field, and helps the Arghosha Faraway Schools in Afghanistan and education for women in India. “I feel that the world is in such a mess because education in general is very bad,” he says, “and in the West the ways of teaching are obsolete, so young people are not being enthused”.

He is dismayed by what he calls the Taliban attitude of some of the Western campaigners against all collecting in the field of antiquities, reinforced by politicians in the source countries who exploit the issue for nationalist reasons. For example, together with the British Museum, he helped finance a curatorial training scheme for Indian curators that was very successful for two years but was then stopped by the Indian government because they saw it as tainted by colonialism. Nothing was put in its place, however, so arguably India was the loser.

Eskenazi went to the headquarters of the Pakistani politician who had the Begram ivories for sale with the intention of restituting them

How Eskenazi found and enabled the repatriation of the Begram ivories to Kabul

Neil MacGregor, the former director of the British Museum, says of Eskenazi: “He is a loyal and very generous friend. When he makes a donation, which happens frequently, he does it without hesitation of the least desire for public recognition. In the case of the Begram ivories he was truly magnificent.” Eskenazi was a key player in the recovery of the ivories from the black market and their repatriation. These small, rare and exquisite, first-century AD sculptures had been looted to order in the 1990s from the Kabul Museum for some Pakistani politicians. Retrieving them was a potentially dangerous, expensive and legally delicate matter, but Eskenazi knew they were too important to be allowed just to disappear so he took the risk of going to the headquarters of the Pakistani politician who had them for sale.

Once they had been recovered, they were brought to the British Museum, conserved and put on display briefly in the 2011 exhibition Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World, at which Hamid Karzai, the then-president of Afghanistan, thanked Eskenazi in his opening speech for his contribution to Afghan heritage. The ivories were then quietly returned to Afghanistan, courtesy of a British military flight, and can now be seen in the rebuilt Kabul museum. Such a solution requires flexibility and good will, however, and Eskenazi fears that in the prevailing culture wars these qualities will not be allowed to prevail.

The rigid application of the Unesco Convention 1970 cut-off date excludes many works of art that came out of their countries of origin much earlier, but whose owners may not be able to prove it. These works have now become almost unsaleable. The consequence, says Eskenazi, is that a whole generation of orphan works of art now exists, owned by elderly collectors who can neither sell them, nor bequeath or even lend them to a museum, which is to no one’s benefit. He quotes the Dalai Lama’s words in the catalogue of the Wisdom and Compassion exhibition at the RA in 1990, after the Chinese had destroyed the Tibetan shrines: “Art belongs to whoever can take care of it for now”. This is obviously not intended give a free pass to looters, but to allow for custodianship, even if only temporary, of works of art that have become detached from their origins.

As for the path he has followed, Eskenazi sees that there was a guiding light. “I may be a superannuated hippy, but I have always hoped that people who come into contact with this art will learn some of the spirituality of Eastern religions,” he says. “After all, the diffusion of Buddhism was only partly through the monks but also through the images of Buddha, the reminder of his great example.”