When the Japanese fashion designer Kenzo Takada set up the first outlet to sell his own clothes in 1970—in an empty space in the grandly arcaded Galerie Vivienne, in Paris—he painted the walls with a jungle scene based on one of his favourite paintings, Henri Rousseau’s colour- and mystery-saturated masterpiece The Dream (1910). Working on his mural gave Takada the idea of calling the shop, and his label, Jungle Jap. That label did not last—it became in time Kenzo—as the term Jap was not just pejorative but brought back, in the US in particular, memories of anti-Japanese hysteria during the Second World War. “I knew it had a pejorative meaning”, Takada told the New York Times two years later, “but I thought if I did something good I would change the meaning.”

But the painting itself was an imaginative grand geste typical of Kenzo, the most artful, and graphically sensitive, of clothes designers, while the tiger at the centre of Rousseau’s composition, staring mask-like straight at the viewer, remains, half a century on, a motif of the Kenzo brand, reproduced on its T-shirts and sweatshirts and sold around the world. Takada created an international reputation for Kenzo, and won it a place as one of Paris’s leading ready-to-wear (and later couture) marques, with his vibrant print fabrics and knitwear where pattern and colour are artfully balanced—inspired first by Japan and later by a multicultural series of influences, from the Far East, Eastern Europe, India and North Africa.

After retiring from Kenzo in 1999, Takada returned to his youthful love of drawing. In 2010 and 2011 he exhibited, in Paris and Moscow, a series of eight self-portraits as a geisha character from a Noh play wearing kimonos with Hokusai-like floral patterns that were familiar to those who had followed his fashion house for the previous 40 years. In everything he did—clothes, spectacles inspired by his trademark round lenses, home furnishings, parfumerie—his love of fine art remained close at hand.

Kenzo Takada was born in 1939 in Himeji, 60 miles west of Osaka, one of five sons and two daughters of a tea-house owner. His early years were clouded by the Second World War and post-war life in a devastated Japan. He had nothing culturally, he remembered, but American films and his own drawings. He later developed a love for fashion from reading his sisters' magazines, and left Kobe University, where he was studying literature, in 1958 to attend the Bunka Fashion College in Tokyo, where he was one of the first male students. In 1960, he was awarded the So-en Prize, by the college’s fashion magazine So-en, and started work designing children’s clothes for the Sanai department store. One of his tutors had encouraged him to travel to Paris and his opportunity came when the government commandeered his flat as part of the preparations for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and gave him ten months’ rent as compensation.

Takada went by ship to Marseilles, seeing Hong Kong, Singapore, Saigon, Colombo, Bombay, Djibouti, Egypt and Spain along the way, and arrived in Paris in 1964. He was cold and hard up, but entranced by the city and a sense of personal liberty. He found work making drawings for a textile company. He found love—his partner of 25 years, Xavier de Castella—and he stayed for the rest of his life. French commentators liked to claim Takada as the most Parisian or the most French of Japanese designers. He was certainly the first, paving the way for Yohji Yamamoto, another graduate of Bunka, and other Japanese designers. “I’ve been in Paris for 55 years, but I still consider myself 100% Japanese,” Takada told the South China Morning Post in 2019. “When I go back to Japan it feels like home, and when I come back to Paris it also feels like home.”

For his 1970 boutique opening he saw no point in mimicking what his French rivals were doing. Working on his own designs, he produced a sweater that was completely square. And that, as he said, “gave him his style”. He mixed some kimono fabric with pieces of material from the flea market to create his own kind of fun, “mix-and-match” street look, loose, often oversized, and with few zippers or buttons. “Fashion is not for the few”, he said. One of his pieces ended up on the front of Elle magazine and international buyers came calling at his 1971 show. By July 1972 he had two shops in Paris, one in St Tropez, others in Dusseldorf and Hamburg and was looking for his first space in New York, where his clothes were already on the shelves of Bloomingdale’s and Saks Fifth Avenue.

His early collections had told the story of his physical and creative journey from Japan to France—the New York Times commented in 1972 that his knitwear was “Impressionist-colored”—and travel, observant travel, remained a key part of his creative process, as he gathered ideas from Vietnam, India, Hong Kong, Eastern European folk dress, and north African kaftans.

When I go back to Japan it feels like home, and when I come back to Paris it also feels like homeKenzo Takada

When he was still studying and working in Japan he had thought little of traditional Japanese dress but a trip to Japan in 1972, on his way to the US, had opened his eyes. “The cutting of a kimono is simple, beautiful,” he told The New York Times, “It is going to affect my work.” With his increasingly multicultural palette he managed to maintain an instantly recognisable style. Simple, chaste outlines; an eye for pattern—checks, grids, flowers, organic shapes—and a Symbolist flair for mixing pattern with fresh, vibrant colours, playing an easy game with complementary and contrasting shades. In Paris, he admired the work of the space-age designer André Courrèges and, especially, that of Yves Saint Laurent, but his work, and his shows, were like nothing the city had seen before.

His collections were fun and theatrical. He was the first to use many models at a time, rather than one marching up and down in chilly isolation. And he was the first, the designer and model Inès de la Fressange told Women’s Wear Daily, to put celebrities on the catwalk. “People would fight to get into a Kenzo show,” she said. In 1972, 800 people were expected to view his collection, and more than 3,000 turned up. It was so crowded that the models could not move. He added an annual couture show to his ready-to-wear line in 1976. His 1979 show was held in a circus tent. At one stage, the models rode in on horses, and Takada on an elephant.

In the 1980s, Kenzo was put on a firm business footing, and diversified into men’s fashion; in 1983, perfumes, household fabrics and scarves. One scarf has a floral design around Holbein’s portrait in profile of Edward Prince of Wales at the age of six.

Takada was the gentlest of men—French broadcasters loved to reference his timidité—and felt it was important for him to be happy in himself: “If you are not happy, you can’t create”. It was said that the one thing that united the warring factions of Paris fashion was their personal affection for Takada. He and De Castella created a completely Japanese house in Paris. It was a calming centre to his hectic professional life where he liked to entertain. But he also loved large parties, dancing and travelling with friends. His joie de vivre kept breaking out. The introvert and extrovert were held in interesting balance. As was the white streak in his fringe, which developed naturally but was carefully maintained thereafter by his hairdresser.

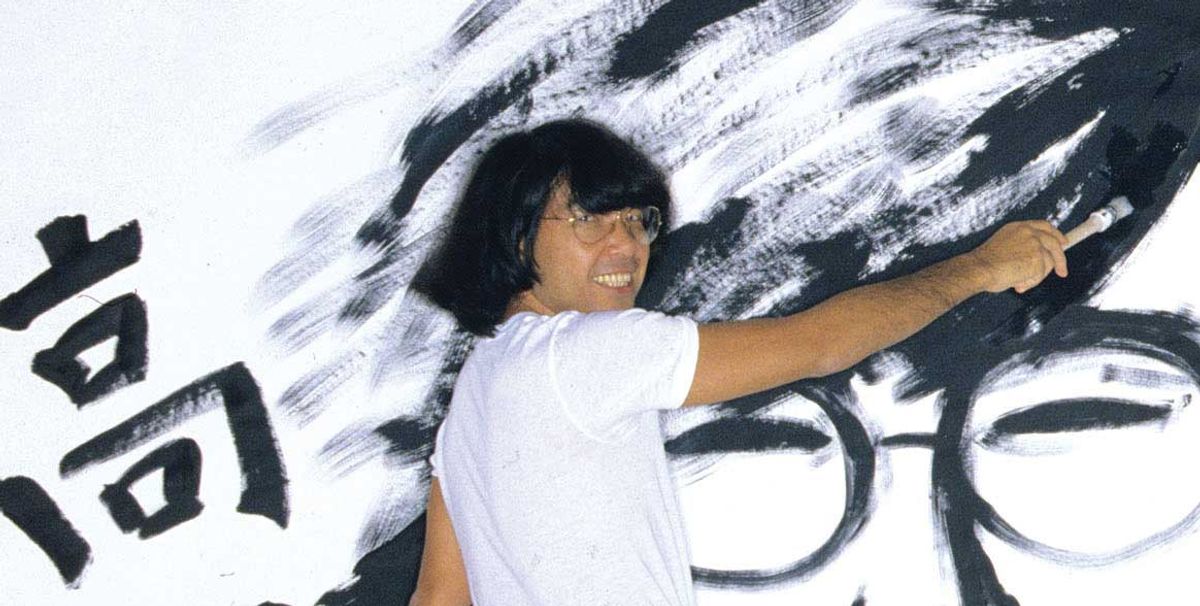

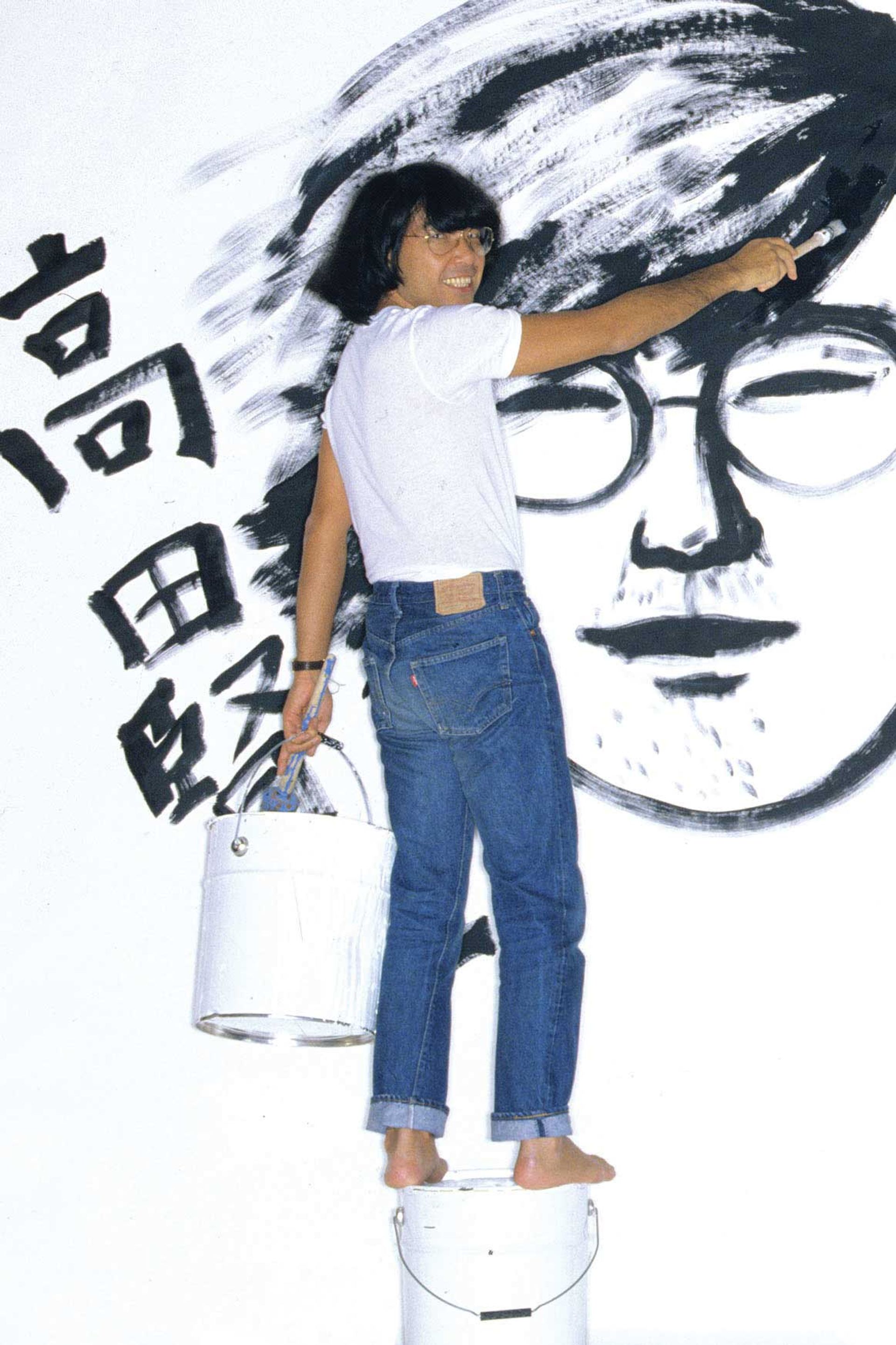

The gentlest of men: Kenzo Takada, photographed for Elle in 1981 © Oliviero Toscani

In 1990-91 he suffered three personal tragedies. His partner Xavier de Castella died, after five years of declining health, in 1990; the following year Atsuko Kondo—the pattern maker who had played a key role in turning designs into finished products—suffered a stroke; and Takada’s mother died while he was off grid, sailing round Corsica. He was devastated to have missed her funeral. At work he found himself at odds with his business manager, and in 1993 sold Kenzo to the luxury goods conglomerate LVMH for $80m, staying on as creative director until 1999.

He was happy to be off the collections treadmill but, after two years of travelling, needed to be back creating. Painting, but also setting up a new homewares brand, Gokan Kobo, in 2004, and designing the costumes for a production of Puccini’s Madame Butterfly in Tokyo in 2019. In January he launched K3, a brand of furniture, ceramics and fabrics. The balance between sober, clean design and expressive colour remained as important as it had been in Galerie Vivienne 50 years before.

In his 2010 self-portraits, Takada was intrigued by his own decision to depict himself as a female character from Noh, with wig and mask. In each picture he uses less mask and shows more face. To him the process felt bizarre, but also pleasure giving. Symbolic of his engagement with that mix of introvert and extrovert. And one more expression of the unstoppable Takada joyousness.

- Kenzo Takada, born 27 February 1939, died 4 October 2020