The Museum for Islamic Art in Jerusalem is due to sell 190 Islamic art objects and 68 rare timepieces from its collection in two Sotheby’s London auctions on 27 and 28 October. The first sale includes illuminated manuscripts, textiles, ceramics and metalwork dating from the 7th to 19th centuries. The second consists of rare clocks, including three watches crafted by the leading 18th-century horologist Abraham-Louis Breguet.

The museum’s director, Nadim Sheiban, declined to be interviewed by The Art Newspaper but the museum explained in a statement that the deaccessioning sales are intended to secure its long-term future and educational programming. Sheiban later added that the objects selected for auction were “mostly duplicates or in storage”. According to a museum spokesperson, the collection comprises around 5,000 items in total.

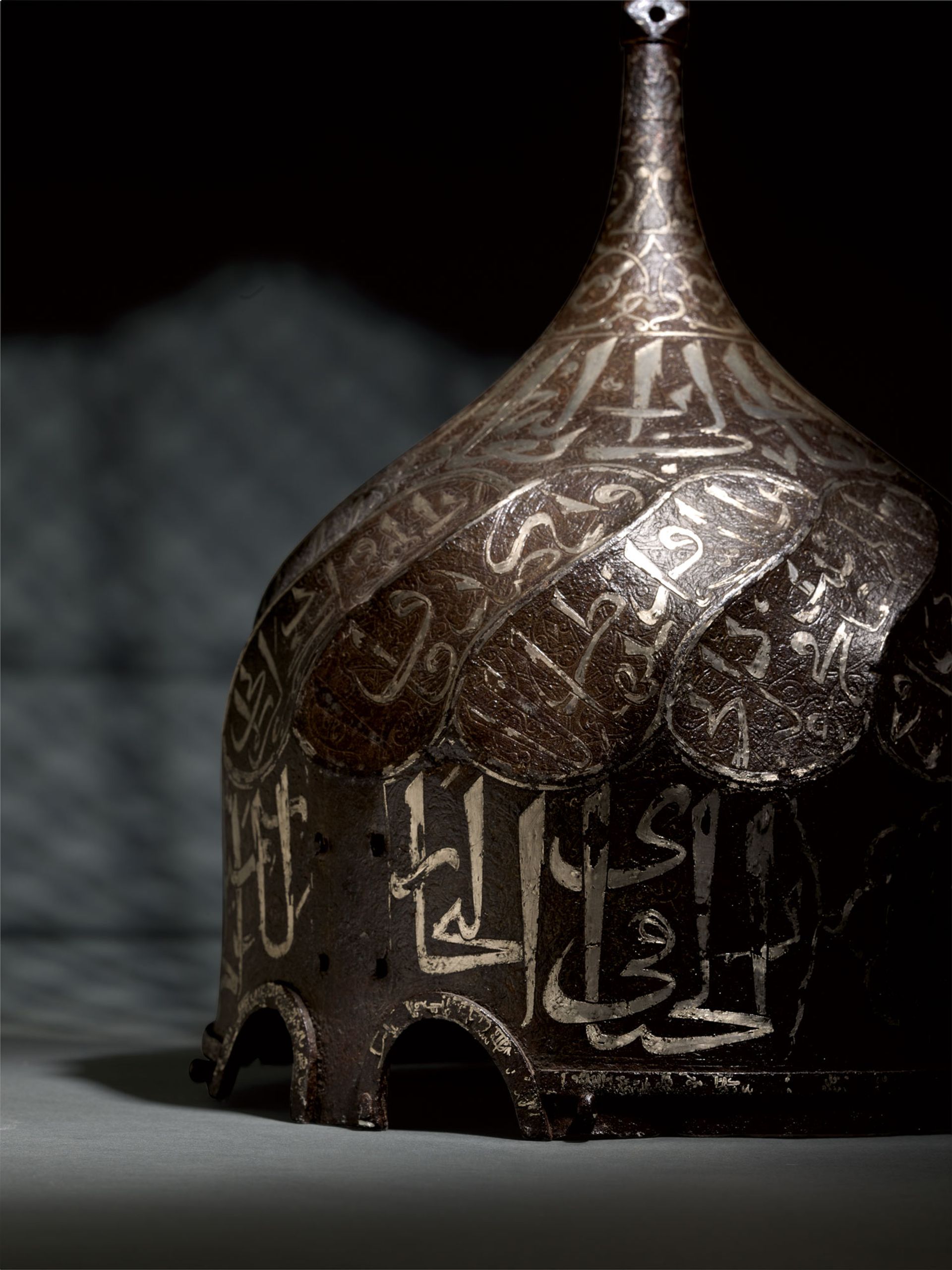

A 15th-century silver-inlaid Aqqoyunlu turban helmet from Turkey or Persia is estimated at £400,000-£600,000 © Sotheby's

The move had been under consideration for two years, Sheiban told the Israeli radio programme Gam Ken Tarbut, in part due to limited government funding for what is “the only museum devoted to Islamic art within this conflict-ridden and divided region”. Sheiban notably became the first Palestinian director of an Israeli museum when he assumed his current position in 2014. “We have important social and educational roles beyond our artistic role,” he said.

But museum professionals from the local chapter of the International Council of Museums (Icom) and the Israel Antiquities Authority have questioned the classification of the deaccessioned artefacts as duplicates, and criticised the wide scope and ethical implications of the sales. “These are special, one-of-a-kind objects that are now disappearing from public view and going into private hands,” says Raz Samira, a photography curator at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and the deputy chair of Icom Israel.

A rare 19th-century watch crafted by Abraham-Louis Breguet, previously owned by the Prince Regent of England, later King George IV, is estimated at £400,000-£600,000 © Sotheby's

Deaccessioning is relatively rare in Israel. In 2011, the Israel Museum in Jerusalem sold 39 works in order to expand its collection, and in 2014, the Ramat Gan Museum of Israeli Art sold a painting by the Russian artist Valentin Serov to fundraise for a new building.

Critics of the Museum for Islamic Art note that it will not use the proceeds to enrich its collection, as advised by Israel’s Museum Law (in effect since 1984) and the code of ethics governing Icom, of which the institution is a member. In the two years spent planning this sale, the museum never sought to place objects with other public institutions that collect Islamic art, such as the Israel Museum or the Museum of Islamic and Near Eastern Cultures in Be’er Sheva.

A loophole in the Museum Law, however, allows Israeli museums to use deaccessioning proceeds as they see fit, even if investing in new acquisitions is strongly advised. Israeli Icom members hope to use this case to lobby lawmakers to close that loophole.

The Museum for Islamic Art in Jerusalem has a collection of around 5,000 objects Photo: Vadim Mikhailov

Samira voices concern that deaccessioning could negatively impact public funding of Israeli museums in general. Since it opened in 1974, the Museum for Islamic Art has been chiefly financed by an endowment established by its founder, the British philanthropist Vera Bryce Salomons. This currently accounts for 70% of the ILS10m ($3m) annual budget, of which around 17% is subsidised by municipal and state government. The institution receives a larger proportion of public funding than Israel’s largest museums, Samira claims. “They’re trying to make their public support look more modest,” she adds. “It isn’t.”

While the museum’s decision was not provoked by an immediate financial shortfall caused by Covid-19, the timing of the Sotheby’s auctions during the pandemic may have allowed them to slip under the radar. Israel had recently entered its second national lockdown in September when the sale was first reported and it has not been widely covered by the local press.

Members of the Israeli museum community fear that the quiet sell-off could set a dangerous precedent. “Other museum directors could now take advantage of this sale, which supposedly took place without issue, in order to sell works from their own museum collections,” Samira says.