Over the last two days, with the Covid-19 infection rate in New York holding below 1%, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art ended a five-month shutdown. At last! Something for deprived New Yorkers to do besides Zoom.

Despite a serious reduction of staff, services, programming and a painful tightening of its belt, the Met, New York’s biggest and most beloved museum, is meeting safety-conscious restrictions with vigour. One innovation is valet parking for cyclists, a boon to locals; in the absence of foreign and interstate travellers, they are the audience.

Rules imposed by the state that limit admissions to 25% of capacity and require everyone to wear a face mask worked changes inside as well. A minute past temperature check, I walked unimpeded down halls that I used to elbow through. Objects I never noticed before came into sharp focus, giving greater clarity to the whole. I felt the difference.

Antiquities looked scrubbed. Paintings were brighter, furniture more polished. Medieval armour seemed borrowed from the future. Even the newly filtered air felt fresh. Anxiety took a powder. Enlightenment replaced it. So did pleasure.

With three new exhibitions on view and 5,000 years of human history within easy reach, the Met really can teach a person everything about life on earth, including how much of the past lives in the present.

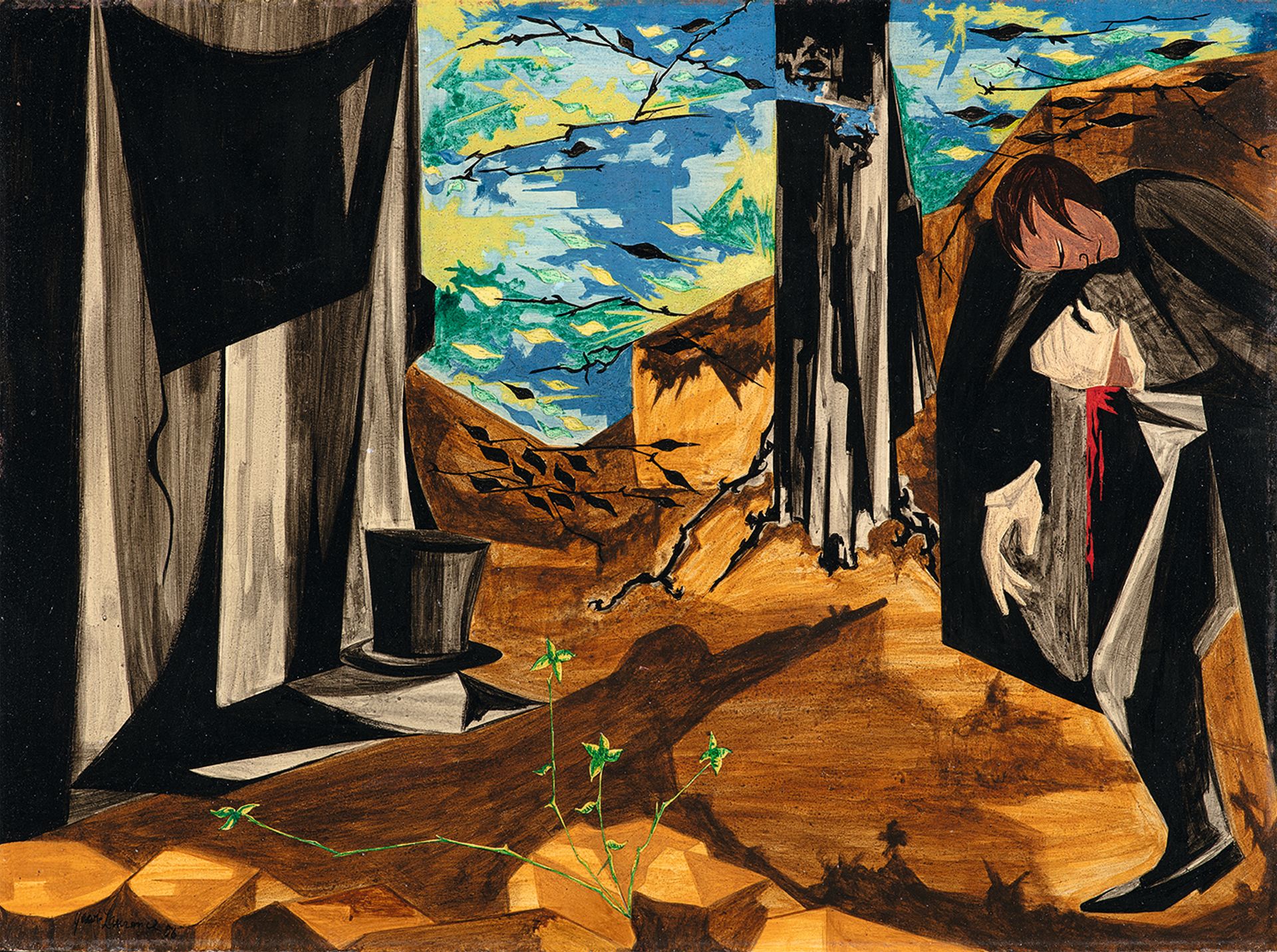

Struggle: From the History of the American People, a little-known series of tempera paintings by Jacob Lawrence, could not be more apt for this moment. Its 30 panels represent the country’s founding, Civil War and westward expansion in a stark, visual narrative of such aching beauty that it almost hurt to look. Each depicts an incident that Lawrence researched in Harlem’s Schomburg branch of the New York Public Library. Scattered by sales after the series’ gallery debut in 1956, most of the panels were reunited earlier this year for exhibition by the Peabody-Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts before travelling here.

Jacob Lawrence, "I shall hazard much and can possibly gain nothing by the issue of the interview"–Hamilton before his duel with Burr, 1804, Panel 17 (1956) from the series Struggle: From the History of the American People © The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Bob Packert/PEM

Two were lost long ago; three others exist only as shadow reproductions. But potent quotations from historical figures, song lyrics, coded messages and the cries of rebelling slaves that Lawrence chose as titles all remain, exposing the violence, exhaustion, frustration and faith in democratic rule that created and compromised this nation. Compressed into 12-by 16-inch space, each image reads at once as a historical record and a timeless abstraction.

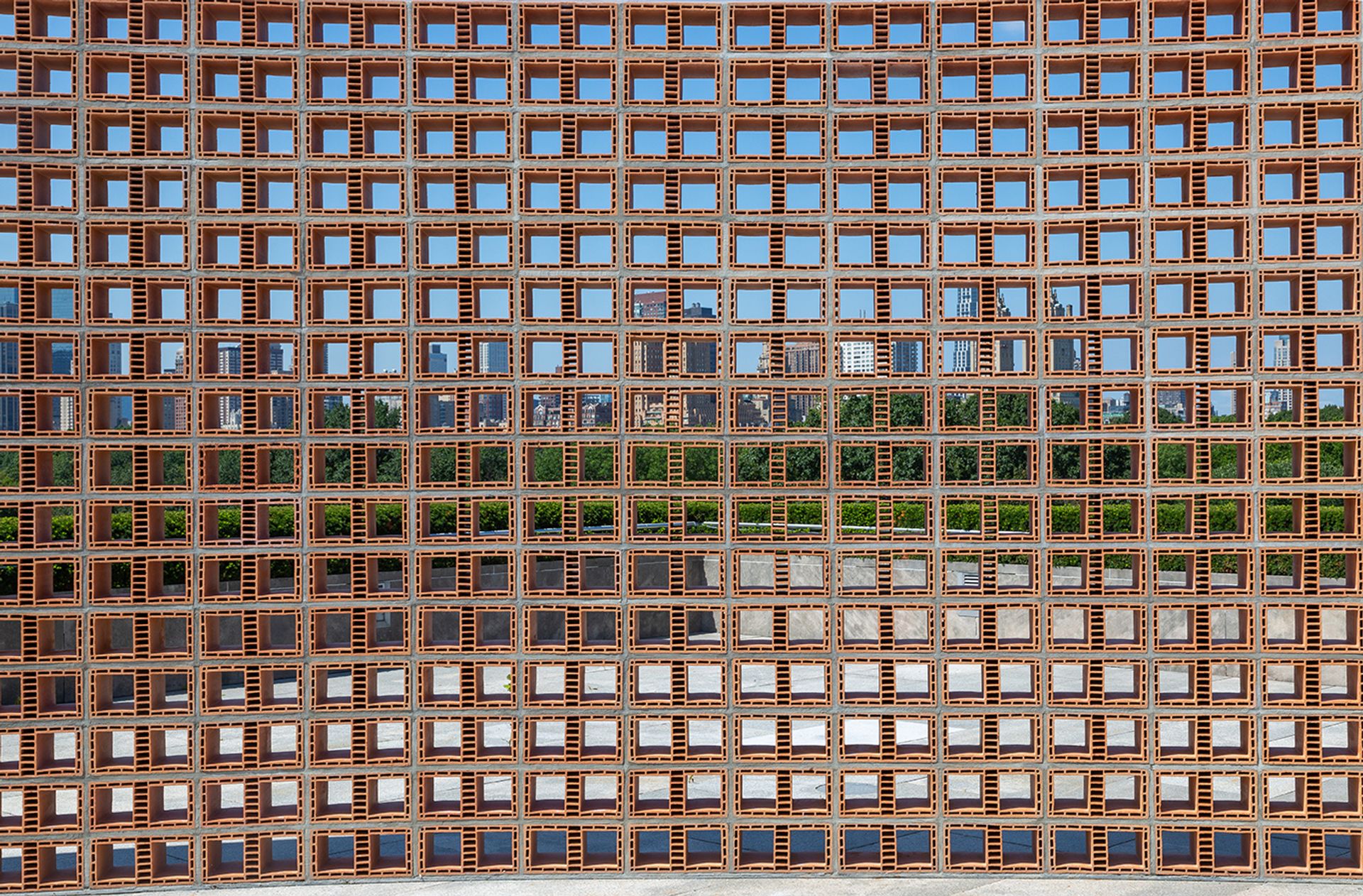

Current politics inform this year’s rooftop commission by the provocative Mexican artist Héctor Zamora. His Lattice Detour is a gently curving brick sculpture that bisects the terrace, bringing to mind Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc, Maya Lin’s Vietnam War memorial and Donald Trump’s obsession with building an impregnable wall on the border between Zamora’s country and this one. The artist’s is real; it’s also an 11-foot high, 100-foot long illusion. At first sight, it appears solid and indifferent. Closer inspection reveals an open grille of hollow clay blocks. Though it is impassable and obscures the the city views, you can see through to the other side, then walk around to look back where you started. Perspectives alter. The border stays put.

Installation view of Héctor Zamora's Lattice Detour (2020), a commission for the roof garden at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Courtesy of the artist. Metropolitan Museum of Art/Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen

Detail of Héctor Zamora's Lattice Detour (2020) Metropolitan Museum of Art/Photo by Anna-Marie Kellen

The Met may be the definition of encyclopaedic, but that doesn’t mean it’s inclusive. Yet efforts to embrace artists and audiences that previous generations patronised from a deliberately unsocial distance are visible in its anniversary show, Making the Met, 1870-2020. I don’t know about you, but I’ve never seen curators anywhere cull more than 250 objects from every museum department and assemble them not by medium, age or geography, but by dates of acquisition.

This gives what might have been a back-patting, greatest-hits account of the Met’s development an abundance of visual zingers that show it struggling to come to terms with its snooty, supremacist roots. It’s also fun.

Who would expect this museum to hang a stunning portrait of the Princess de Broglie by Jean-Louis Ingres between a fragment of Netherlandish tapestry and three panels of a gilded 14th-century altarpiece? A van Gogh opposite Richard Avedon’s Marilyn Monroe? To position a seated Queen Hatshepsut (1479–1458BC) before a newly revealed window framing Cleopatra’s Needle in Central Park is inspired placement. To drape an enormous golden weave of fishnet and bottlecaps by Ghana’s El Anatsui beside a bronze bough by Mrinalini Mukherjee to background the exquisite pairing of the 17th-century Crown of the Andes and a weighty silver Torah cap made a century later isn’t just thinking but leaping out of the box.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Joséphine-Éléonore-Marie-Pauline de Galard de Brassac de Béarn, Princesse de Broglie (1851–53) Metropolitan Museum of Art

An installation view in Making the Met, 1870-2020, that includes El Anatsui's textile work Dusasa II (2007). Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art

An installation view of Queen Hatshepsut (1479–1458BC) before a newly revealed window framing Cleopatra’s Needle in Central Park Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art

This is the one spot in the museum that reminded me of old times. Even with guards controlling the pace of circulation through a corridor that opens to individual galleries, it’s impossible to maintain a respectful distance between viewers. In one small space, six people were a crowd. That made me nervous, but it didn’t seem to bother anyone else. All eyes were on the art.

If it took 150 years, a global pandemic, a few scandals and new leadership to make the greatest museum in the world, so be it. Even absent the spectacle of its spring gala (cancelled this year), under director Max Hollein the Met isn’t just open. It’s alive.

After such nonstop splendour, the monochromatic MoMA seemed underdressed. That’s unfair. It’s wrong to compare. But, weirdly, it also gave the impression of being stuck in time. Probably, that was because nearly all of the temporary exhibitions that opened before the shutdown are still on view, with unchanged installations in the expanded collection galleries. Anyone who held out, fearing crowds, should take the plunge now. On preview day, the only other person in most galleries was a guard. This situation is bound not to last, but having so much room to move certainly enhanced the Minimalist work of Donald Judd, which benefits from solitary viewing.

An untitled work by Donald Judd (1991) in a retrospective at the newly reopened Museum of Modern Art © 2019 Judd Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: John Wronn

At this point, needing a rest, I headed to the darkened Kravis Studio, where the new installation of a vintage 1968-69 multimedia work by Shuzo Azuchi Gulliver offered seating, on a stool. I could have been a wallflower at a nightclub like Tokyo’s Killer Joe, the underground disco for which Gulliver made Cinematic Illumination. The action, set to an electronic soundtrack, was on a large zoetrope-like drum hanging overhead, the circular projection screen for 1,500 black-and-white images of everyday people in movies and magazines. Unlike the mirrored-ball effects playing up and down the walls, it didn’t spin, but it made me dizzy anyway.

Shuzo Azuchi Gulliver, Cinematic Illumination, 1968–69 Courtesy of the artist and the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Felix Fénéon (1861-1944) is one person I’d like to have met on a dance floor—or at Le Chat Noir, the early 20th century’s Mudd Club of Paris. The acerbic French critic, collector, dealer and anarchist is the subject of the museum’s other new exhibition, the first to explore his unusual life and career as the champion of MoMA mainstays like Seurat. Signac, Toulouse-Lautrec, Bonnard and especially Matisse. (Fénéon was his original gallerist.)

Henri Matisse, Interior with a Young Girl (Girl Reading), 1905–06. Oil on canvas. 28 5/8 x 23 1/2″ (72.7 x 59.7 cm). Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. David Rockefeller, 1991. Photo by Paige Knight. © 2019 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

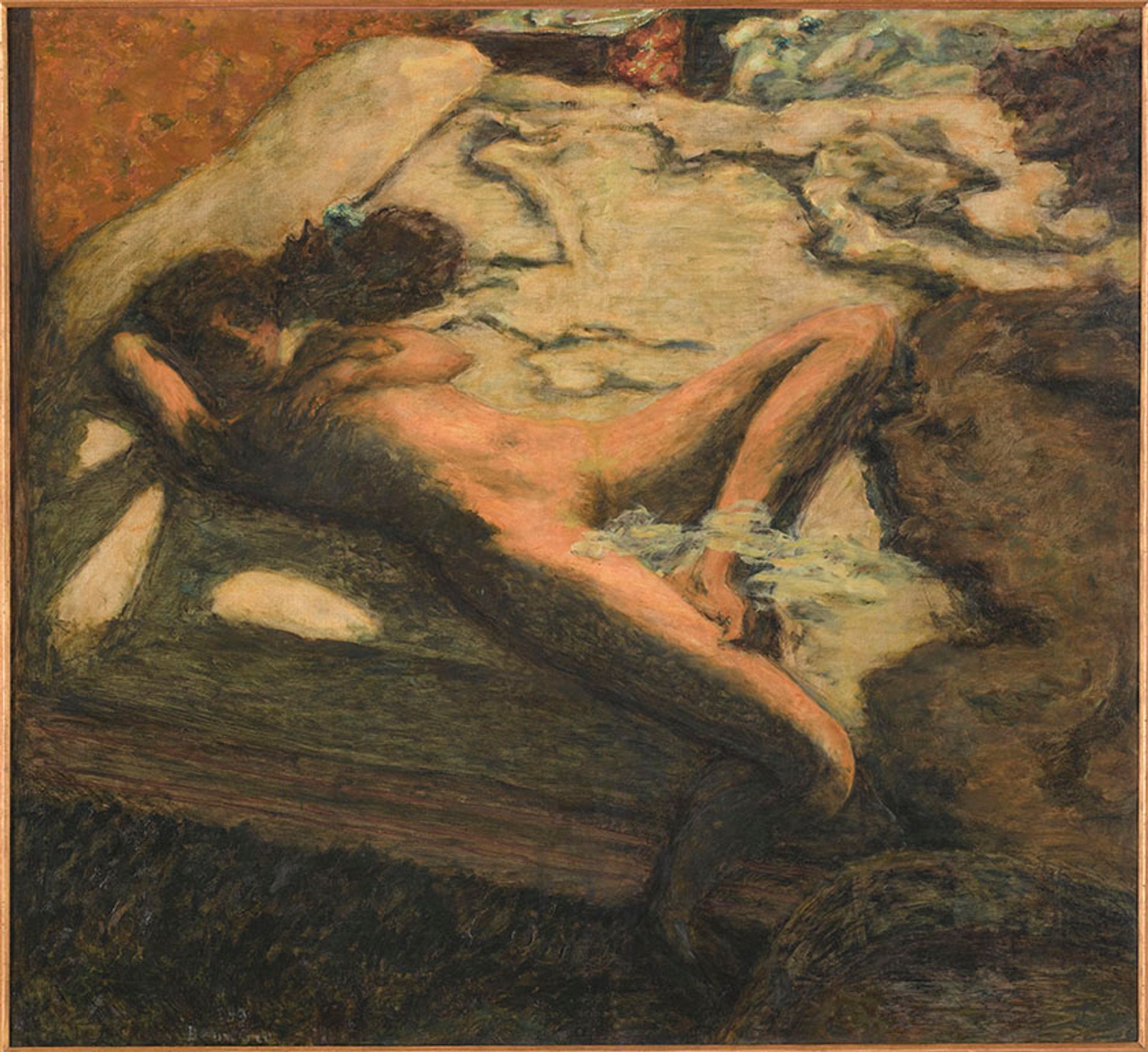

Loans include a striking erotic nude by Bonnard that had stayed with Fénéon, who also went in for sculpture from Africa and Oceana. Also diverting are materials relating to his arrest and trial as a bomb-throwing radical. And take this snippet from a satirical newspaper column he wrote anonymously: “Schied, of Dunkirk, fired three times at his wife. Since he missed every shot, he decided to aim at his mother-in-law, and connected.”

Pierre Bonnard, Woman Dozing on a Bed (1899) © RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Other museums will reopen in coming weeks, following the same guidelines as MoMA and the Met. One day we’ll get the all-clear, tourists and commuters will return, and people will gather again for selfies in large groups. Until then, these hard-pressed institutions are plugging holes in the city’s cultural life, providing a recourse to calm at a time of justified unrest. After all, as the Milton Glaser mural in MoMA’s lobby says, they ♥︎ New York, too.

Milton Glaser, I ♥ NY logo, 1976, in the lobby at the Museum of Modern Art New York State Department of Economic Development, used under license by the Museum of Modern Art