When a group of Europe-based ethnology experts in April announced plans to create a digital inventory of works of art looted from the Kingdom of Benin, some people were skeptical. “Will they also be digitally repatriated?” asked one Twitter user somewhat caustically.

The so-called Benin bronzes have become a touchstone to test European museums’ readiness to restitute heritage looted from Africa in the colonial era. After the violent 1897 plunder and devastation of the Royal Palace of Benin by British troops, at least 3,000 artefacts were dispersed internationally—probably many more.

Only a few have been restituted. Cambridge University’s Jesus College, for example, announced last year it would return a bronze cockerel bequeathed to it in 1930 by a British army officer.

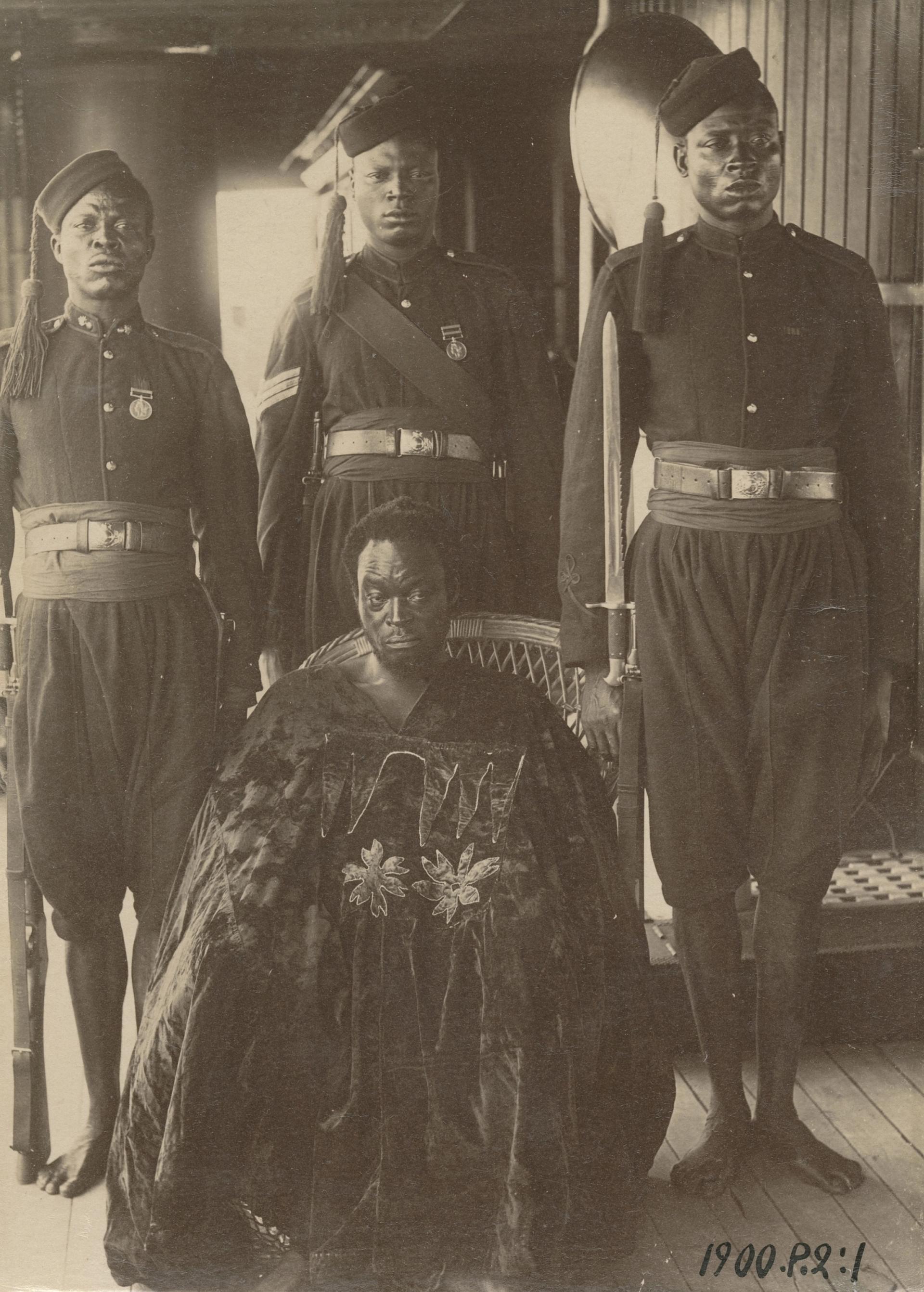

The captured Oba Ovonramwen on the British yacht Ivy on the way to exile in Calabar Photo: J.A.Green, 1897 © MARKK

As yet, none of the major European museums with holdings of looted Benin artefacts has committed to return them permanently. “Sometimes it looks like everyone is dancing around the main point,” says Victor Ehikhamenor, an artist from Benin who contributed to the Nigerian pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. “It’s still a bit murky, and a bit slow.”

Stopping short of promising full repatriation, the Benin Dialogue Group, whose members include the British Museum, Vienna’s Weltmuseum, Oxford University’s Pitt Rivers Museum and Berlin’s Ethnology Museum, agreed in 2018 to “contribute from their collections on a rotating basis” to a future Royal Museum in Benin City.

Barbara Plankensteiner, the director of the Museum am Rothenbaum in Hamburg, heads the Digital Benin initiative and is a founder member of the Benin Dialogue Group. She points out that the group cannot make decisions for individual museums on repatriation.

She adds, though, that there is no reason why loans and repatriations can not happen simultaneously. “One doesn’t rule the other out,” she says. “It’s clear that significant parts of Benin collections should and will be handed back. The prospect of a new museum has added impetus.”

A year ago, the Edo State Government—which together with the Royal Court of Benin and the National Commission for Museums and Monuments comprises the Nigerian members of the Benin Dialogue Group—said it will set up a trust responsible for planning the museum. The architect David Adjaye presented his vision of the museum to the group. An international fund-raising campaign is also planned. But the coronavirus pandemic, and elections this year in Edo State, risk pushing the project, which was due to be completed in 2023, further into the future.

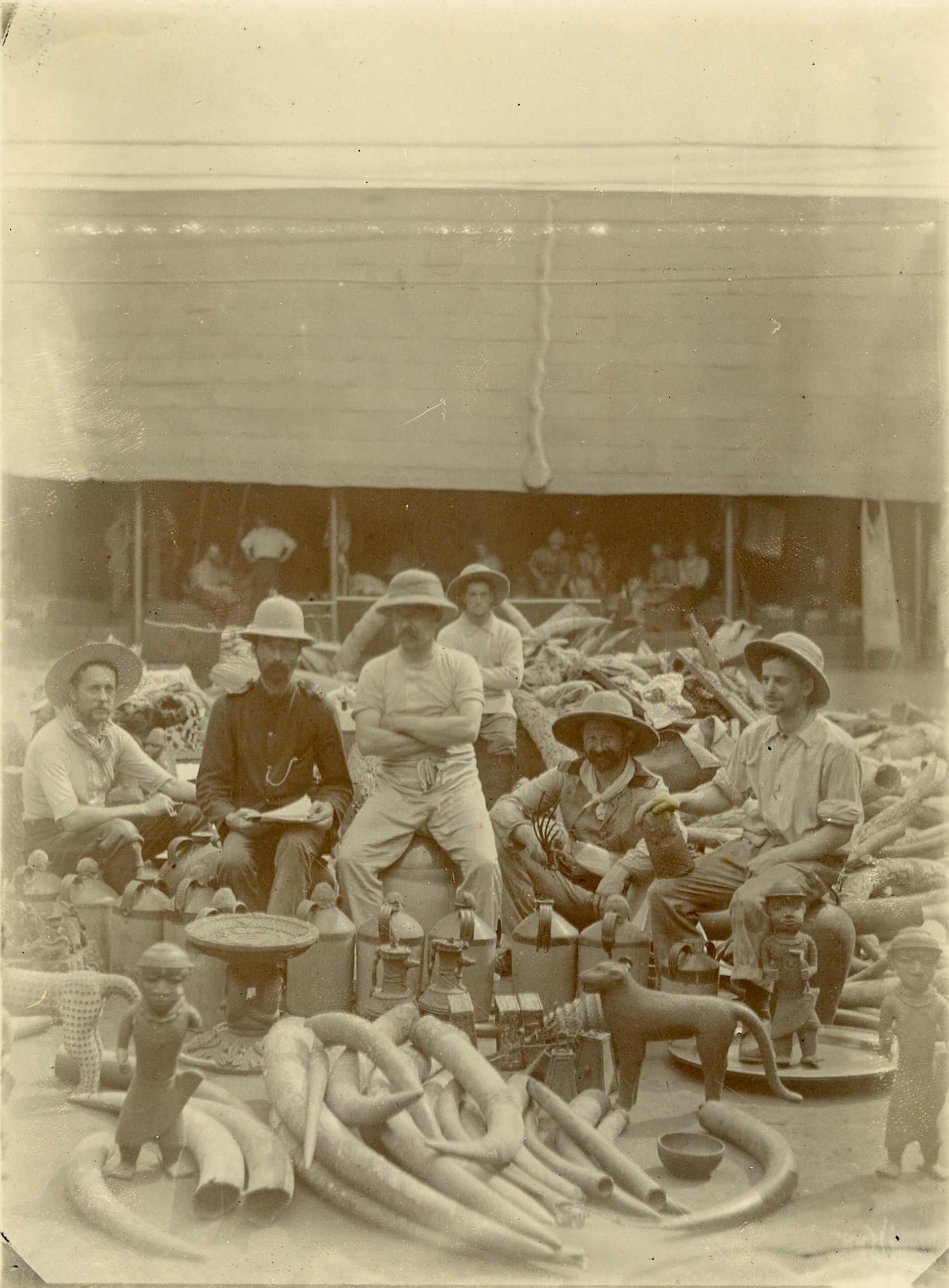

British soldiers with looted art treasures from the Royal Palace in Benin © 2020 The Trustees of the British Museum

Dan Hicks, a curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum and professor of contemporary archaeology at Oxford University says the new museum “is seen by some as the moment at which the next steps will be made, but much global activity is moving forward.” He expects that Digital Benin, whose website is due to be launched in 2022, “will undoubtedly serve to increase awareness of the case for full, permanent restitution of the 1897 loot.”

With funding of €1.2m from the Ernst von Siemens art foundation, Plankensteiner’s team consists of Felicity Bodenstein of the Sorbonne University, Jonathan Fine of Berlin’s Ethnological Museum and Anne Luther, an expert in digital humanities. The project will have offices in Hamburg and Benin City and has advertised for staff.

For scholars in Nigeria, who have struggled to get access to both the objects and archive material that is mostly outside the country, the database is a welcome prospect. Many of the works seized from Benin are intrinsically connected to rites and ceremonies and some of the reliefs record historic events in the kingdom.

“I like to see it like a book,” says Kokunre Eghafona, professor of cultural anthropology at the University of Benin. “The looting was like a book being torn to pieces and then the pages were put in different places. Gathering them together in one place is great.”

“The looting was like a book being torn to pieces and then the pages were put in different places."Kokunre Eghafona, professor of cultural anthropology at the University of Benin

The database will encompass works created from the 15th century to the 19th century, uniting archival materials, eyewitness accounts and oral traditions on the history, cultural significance and provenance of the objects. It will first focus on the 2,000 or so objects in collections in the museums in the Benin Dialogue Group.

In the long term, the future Royal Museum in Benin City is designated as the main coordinator of the project. Hicks says it’s important the group ensures the project is genuinely and sustainably anchored in Benin.

Memorial head of a Benin king (19th century), in the Museum am Rothenbaum, Hamburg © MARKK

“In any digital curation project, we must ask who is framing its aims and aspirations, who controls the scope, pace and freedom of its development, where the data is archived and by whom that data is owned,” he says. “The first two questions for us Europeans must be – what would neo-colonialism look like, and are we sure that’s not what we’re doing?”

While it may be some years before the Benin bronzes are reunited in a non-virtual space, Hicks says progress is happening behind the scenes. In his forthcoming book, “The Brutish Museums,” he argues that international guidelines similar to those for Nazi-looted art would help to accelerate the pace of restitution.

“With the Washington Principles of 1998, the onus for understanding provenance moved from the claimant to the museum,” Hicks says. “That is what we now urgently need in cases of colonial spoliation.”