For more than a century, 820 Fifth Avenue has been one of the most sought-after apartment buildings in New York City, with one 7,000 sq. ft dwelling to each floor. In recent years its best-known occupants were the late Charles and Jayne Wrightsman, collectors of French furniture and Old Masters, and great benefactors of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

When the artist and photographer Peter Beard was born in 1938—the middle of three sons of Anson McCook Beard, a New York City stockbroker, and his wife Roseanne Hoar—his warm-hearted, unstuffy paternal grandmother Ruth Hill Beard and her second husband Pierre Lorillard V (a fifth-generation tobacco magnate and Peter’s step-grandfather, after whom he was named) lived on one of the favoured upper floors of “820 Fifth”, with a view over Central Park Zoo to the south end of the park.

This commanding view spoke of the Golden Age wealth that Beard was born to, one of the co-heirs to the fortune left by his railroad tycoon great-grandfather James Jerome Hill—the art-collecting “Empire builder” who opened up the American Northwest with his railway network, in league with JP Morgan and the Vanderbilt family—and was a metaphor for the social heights in which Beard moved in Manhattan. He was one of a large clan that migrated as the seasons (and convenience) dictated from the city to Long Island to Tuxedo Park, the gated community in the mountains an hour north of Manhattan, built by Beard’s step great-grandfather Pierre Lorillard IV in 1885-86.

Commanding view: Central Park South, New York, photographed from the apartment of Beard's grandmother Ruth Hill Lorillard and her second husband, Pierre Lorillard V, in 1938, the year of Beard's birth, by Pierre's niece, the artist Daphne Pollen Daphne Pollen

Such was the social dazzle that the free-wheeling, film-star-handsome Beard lived in—feted as a mix of James Dean, Lord Byron and Tarzan; married three times, first to the socialite Minnie Cushing, and then to the supermodel Cheryl Tiegs; collaborating or plain hanging out with Francis Bacon, Andy Warhol and Salvador Dalí; stepping out with Jackie Kennedy’s sister Lee Radziwill, while partying at Studio 54 with Andy Warhol, Truman Capote and Mick Jagger— it is easy to lose sight of what an arresting and sometimes prophetic artist he was, especially with his photographs of the early 1960s that revealed the devastating effect of overcrowding and starvation on the elephant population of East Africa.

Such was the social dazzle that the free-wheeling, film-star-handsome Beard lived in ... it is easy to lose sight of what an arresting and sometimes prophetic artist he was

Peter and his brothers Anson junior and Samuel spent their early childhood in Alabama, where their father served in the armed forces, and otherwise grew up in New York, with summers spent on Long Island, with the rest of the year spent in the idyllic lakeside woods at Tuxedo Park. Their grandparents Ruth and Pierre Lorillard lived between 820 Fifth, a house on Long Island (flooded and filled with sand by the September 1938 hurricane nicknamed the Long Island Express), a winter redoubt on Jekyll Island, off the coast of Georgia, and Chastellux, a 52-room French chateau built for Ruth in 1929, the largest house at Tuxedo.

Ruth’s sister Clare Lindley owned another mansion at Tuxedo, Lindley Hall, and their sister Gertrude Gavin had embellished her estate at Graenan, near Brookville, Long Island, by importing a medium-sized French chateau as well as the early 15th-century chapel, from Chasse, near Lyon, where Joan of Arc had once worshipped (the chapel of St Joan was donated to the Jesuit fathers at Marquette University, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and moved there in 1966). The Hill sisters (there were eight in all, and two brothers) were devout Catholics and both Chastellux and Lindley Hall were ultimately bequeathed to a Catholic girls’ school.

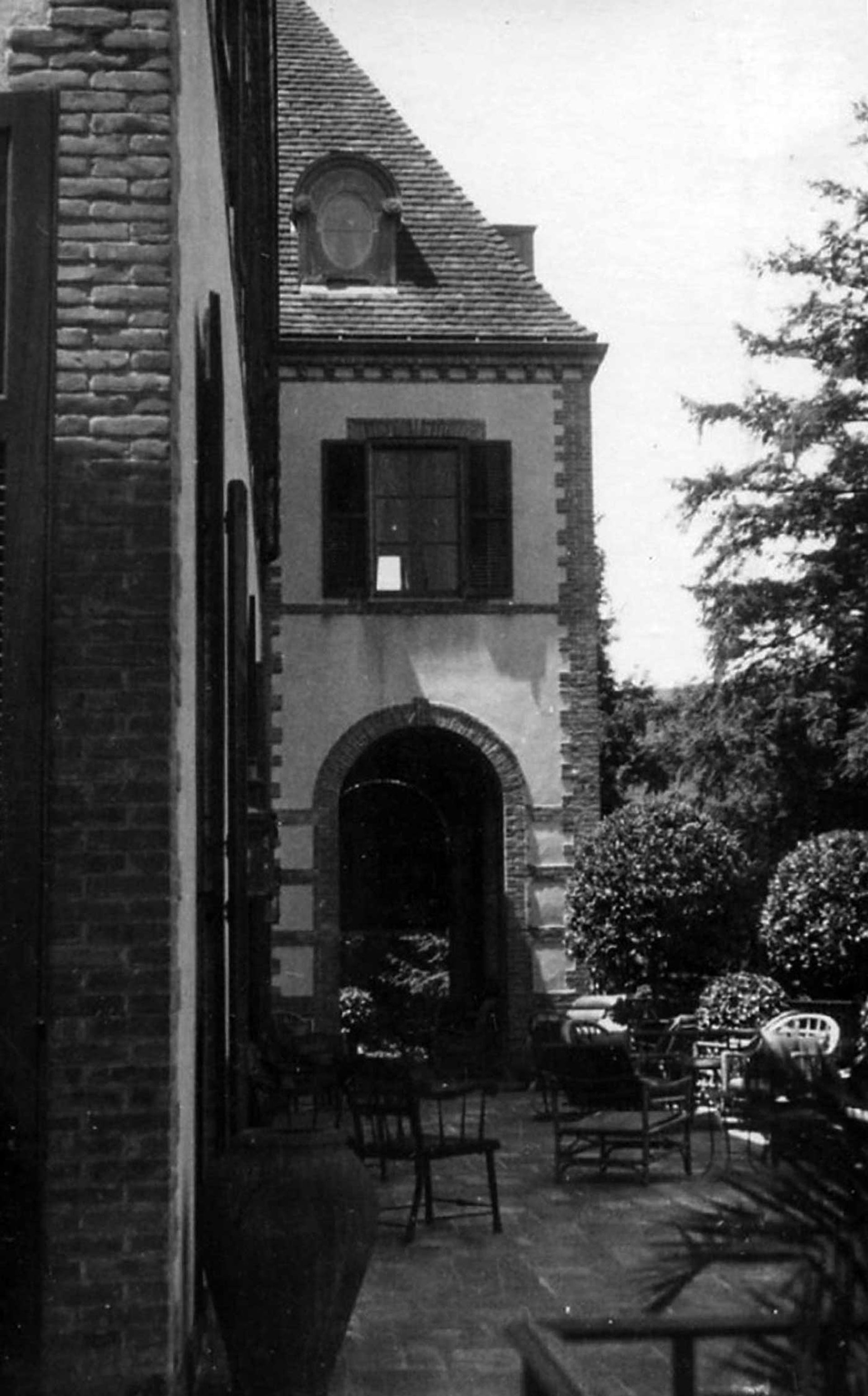

Lakeside idyll: the garden front of Chastellux, photographed in June 1938 by Beard's step-cousin Daphne Pollen Daphne Pollen / Private collection

At the first autumn ball at Tuxedo in 1886, Griswold Lorillard (younger brother of Beard’s step-grandfather) and his Yale friends had worn tail-less dinner jackets, a fashion picked up from the Prince of Wales’s set in London, and the name “tuxedo” stuck. Beard, in an interview with his former publisher Steven HL Aronson in the latest edition of the compendium volume Peter Beard (2020), says: “I find it amusing to be related to the inventor of formal wear, since I’m so sloppy myself.”

It was the exclusive society that Jay Gatsby aimed to break into with his extravagant parties. Beard, who was very aware of his Hill ancestry, delighted in noting that, “F. Scott Fitzgerald has Gatsby’s father saying, when he learns his son is dead, ‘If he’d of lived he’d of been a great man. A man like James J. Hill. He’d of helped build up the country.’ ”

The terrace at Chastellux, 1938, photographed by Beard's step-cousin Daphne Pollen Daphne Pollen/Private Collection

Beard sometimes said he was a “black sheep” to his establishment family, and yet it contained the mentors who set him on a life’s work as documentarist and fashion photographer, rooted in his love of East Africa and its big fauna, and admired from the 1960s by Francis Bacon, Andy Warhol and Salvador Dalí. In 1977, one of Beard’s photographs–of a crocodile–was chosen by the astronomer Carl Sagan and his committee to be included on the “Golden Record” that was carried by the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 Nasa space probes, containing sounds and images from Earth as time capsules for any intelligent civilisation that might encounter them in interstellar space.

I find it amusing to be related to the inventor of formal wear, since I’m so sloppy myself.Peter Beard

Beard’s maternal grandmother, a practising lawyer, gave him the Voigtländer camera he started experimenting with while at the Buckley School, New York, and his first role model was his father’s cousin Jerome Hill (1905-72), painter, photographer, composer, artist and filmmaker (his Albert Schweitzer won the Academy Award of Best Documentary in 1957). To Beard, he was the “ultimate Renaissance man. He was friends with everyone, from … Schweitzer and Carl Jung to Brigitte Bardot. He had a great art collection, great houses, great everything”. Jerome Hill created two foundations that support emerging artists—the Jerome Hill in the US and the Camargo in Cassis, in the south of France.

Jerome’s house, La Batterie, near Cassis, became a second home to the young Beard. The easeful Riviera life is captured in Beard’s 1959 diptych Cousin Jerome Hill and BB (Brigitte Bardot), where a T-shirted Jerome and a bikinied Bardot sit chatting in dappled sunlight on a low rubble wall. Beard painted and drank in the culture of La Batterie. Jerome framed all his pictures. “I was chuffed,” Beard told Aronson, “to be put next to Picasso, Braque and Wols”.

In to Africa

The landscape that made Beard’s name was far grander and wilder than the upper East Side of New York, or the purple hillsides around Cassis. At 17, during his last year at Pomfret College, Connecticut, he took his first trip to Africa and spent the summer photographing in South Africa, Madagascar and Kenya. His guide was the explorer, film-maker and bibliophile Quentin Keynes (1921-2003)—the son of the scholar collector Sir Geoffrey Keynes, nephew of the economist John Maynard Keynes, and great grandson of Charles Darwin—who the previous year had made the first film of the Great Sable antelope, and who went on to amass a matchless collection of travel books and manuscripts, especially those relating to the Victorian explorer Sir Richard Burton.

This introduction to Africa fitted a pattern of Beard’s charmed youth where ideal, and often unusual, guides came into his life—Salvador Dalí was later a mentor to the young Beard and unnervingly insisted that Beard was Dalí's dead brother. At Yale, where he majored in art, Beard studied with Joseph Albers, Neil Welliver, Al Katz and the art historian Vincent Scully, and started to shoot pictures for Condé Nast in the late 1950s while still a student. After leaving Yale in 1961, he returned to Kenya, where he made many of the connections that led to him making the country his second home. During that trip, he travelled to Copenhagen to meet Karen Blixen, author of Out of Africa—the introduction was made by Jerome Hill—and he later bought, with presidential exemption from Jomo Kenyatta, Hog Ranch, 45 acres of wilderness facing the Ngong Hills, and next door to Blixen’s old coffee plantation outside Nairobi. At Hog Ranch, Beard put up a group of safari tents and a studio for his books on Africa, which he had bought at auction from the collections of departing settlers.

Beard’s breakout work was The End of the Game (1965), a mix of his haunting black-and-white photographs and forceful text, documenting the starvation through overcrowding of tens of thousands of elephants, rhinos and hippos in Kenya’s Tsavo lowlands and Uganda parklands—in the aftermath of the changes wrought by big-game hunters and settlers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “The deeper the white man went into Africa,” Beard writes, ”the faster the life flowed out of it, off the plains and out of the bush... vanishing in acres of trophies and hides and carcasses.” When the 50th anniversary edition of the book was published in 2015, the travel writer Paul Theroux pointed out in an introduction that Beard’s work was an “unambiguous warning about humans and animals occupying the same dramatic space”.

One who saw the book's point immediately was Francis Bacon. They met at the opening of Bacon's new show at Marlborough Fine Art, London, in March 1967. Bacon had recently read The End of the Game, and was moved by the images of decomposing elephants, “their carcasses gradually transformed into grandiose sculptures, which beyond simple abstract forms bear the imprint of the vanity and tragedy of life”. Bacon made a series of nine portraits and four triptychs of Beard in the 1970s, while Beard shot a unique set of photographs of Bacon at work in his studio at Reece Mews in west London (200 of Beard’s photographs were found after Bacon’s death on the floor of the studio).

When the 50th anniversary edition of The End of the Game was published in 2015, the travel writer Paul Theroux pointed out in an introduction that Beard’s work was an “unambiguous warning about humans and animals occupying the same dramatic space”

A 1977 edition of The End of the Game was the occasion for a landmark show at the International Center of Photography in New York, when Beard hung a giant poster of one of his elephant photographs, four storeys tall, wrapped around the building’s facade. In the night before the show’s opening, the poster was shredded by a winter squall, and Beard was pictured the next morning, darting about the Fifth Avenue traffic rescuing the fragments. His photograph of the poster in place survives.

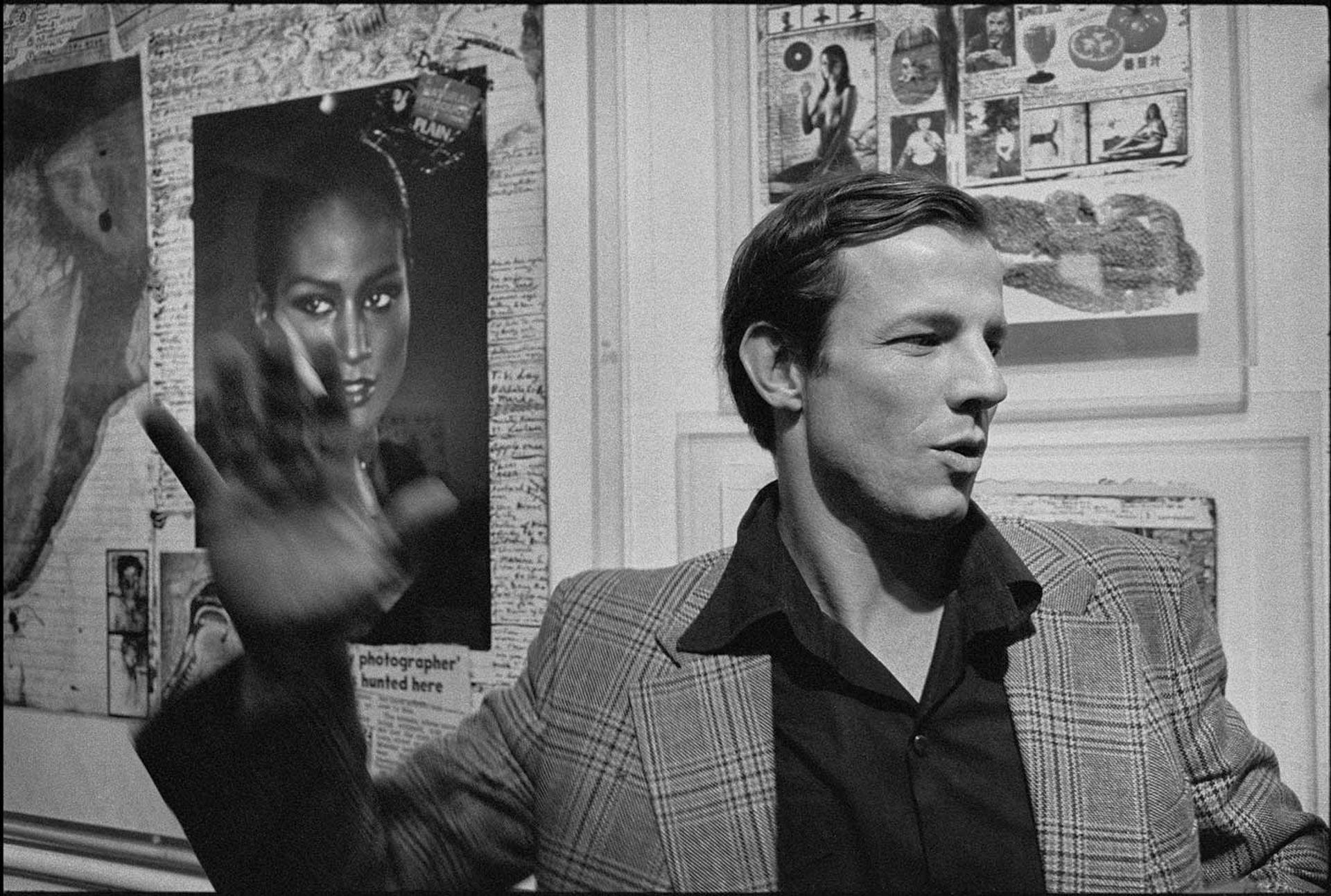

Beard at the opening of his show at the International Center of Photography, New York City, November 1977 Chuck Fishman/Getty Images

Beard's 'trip books'

From the 1960s, Beard had become known for four types of work. His photography of East African wildlife, first showcased in The End of the Game, with new images added to its revised editions; fashion photography, some of it showcasing the supermodels of the day—including Veruschka and Iman—in the context of African wildlife and landscape; his minutely worked diaries, in a style he had developed as an adolescent which combines photographs, calligraphy, drawing and newspaper clippings—Warhol called them Beard's “trip books”, Dalí's comment was "Mr 'Bird' it's the quantity"; and his collages, with drawings, bones, stones and other found objects layered around them as frames—he collaborated with Warhol on a 27-page collage, Introduction to the Things of Life. The artists’ workshop Beard set up at Hog Factory to nurture Kenyan talent produced collages with and for him on an ever greater scale.

Beard’s marriage to Minnie Cushing was short-lived and in the summer of 1971 he found himself thrown together with Lee Radziwill, the younger sister of Jackie Kennedy, while staying with Jackie and her second husband Aristotle Onassis on his island of Skorpios in Greece. Radziwill accompanied Beard and Truman Capote when they were commissioned by Rolling Stone magazine to cover the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street tour of the US. In the summer of 1972, Radziwill, who was renting Andy Warhol’s house at Montauk, Long Island, started to work with Beard on a film about her summer childhood in East Hampton nearby, a project that came to focus on her wildly eccentric aunt Edith Bouvier Beale and her daughter, Little Edie, who lived like hermits in their ramshackle mansion, Grey Gardens, with 52 cats and an overgrown yard, rooms piled high with broken furniture and bric a brac, seemingly stuck in place since the Long Island hurricane passed through 34 years earlier.

Jackie Onassis joined the project, bringing her family albums to show to her relations, while Beard brought in first his film-maker friend Jonas Mekas and later Albert and David Maysles (who had made the documentary Gimme Shelter with the Rolling Stones in 1970). The Maysles brothers ultimately made their own documentary, Grey Gardens (1975), which has since acquired cult status, spawning a musical and a film. But the original Beard and Radziwill footage survived, and this, with some of Warhol’s archive footage, was turned into That Summer (2017) by the director Göran Hugo Olsson, with voiceover from Beard, and the artist filmed at work on one of his collages. "They were in a dreamworld," Beard says of Big Edie and little Edie, "and it was OK."

Bacon and Van Gogh

In 1988, Beard helped Yolande Clergue, the curator wife of the photographer Lucien Clergue to persuade Bacon—who had in 1957 painted three pictures in tribute to Van Gogh's Painter on the Road to Tarascon (1888)—to make a new work for the inaugural exhibition of the Fondation Van Gogh in Arles. Anne Clergue, the curator daughter of Lucien and Yolande Clerge, has published a charming account of how Beard pulled together one of his giant collages as his own contribution to the opening of the Fondation: "One summer day, we went to the beach with a few friends and Peter asked us to select objects for the work he was going to do. He would stick shells, algae, driftwood, ropes, plastic bottles, dead fish, all kinds of garbage collected on the beach on the huge black and white photo which represented him, face down, arms spread out. The day we had to bring the work to the Van Gogh Foundation, we had to find a very wide roll of several metres in order to transport the image, which had grown very heavy with all the objects that made it."

Hard-partying social magnet

In November 1996 Beard was given a full-blown retrospective in Paris: Carnets Africains at the Centre National de la Photographie. Just two months before, he had nearly lost his life while picnicking with friends in Kenya, when a female elephant came at the group "like a freight train", gored and head-butted him, and narrowly missed his femoral artery. He barely survived.

Eight weeks after the attack, Beard attended his Paris retrospective, which included his closely worked diaries blown up to a large size, the dead elephant photographs from the 1960s, and images taken for Paris Match in the 1990s of the burning of giant pyres of elephant tusks and rhino horns, in Nairobi National Park. He was to be found daily at the show, reclining on a mattress (he was still learning to walk again), shod in African sandals, usually in the company of the leading fashion models of the day. He remained into his late 70s the hard-partying social magnet he had always been.

In 1977, Beard’s house at Montauk, Long Island, had burned to the ground, destroying many of his negatives, 20 years of diaries—which he had developed as a collagist work from adolescence—all his African books, and works by Richard Lindner, Bacon, Picasso and Warhol: “Christmas and birthday gifts—Mao and the Jap flowers and all those silk screens”.

Securing Beard's legacy

In the early 1990s, Beard spent long periods in Africa with his third wife, Nejma Khanum, and their daughter Zara. She "was always flawless", Beard said of his daughter, and collected the stories he told her in Zara's Tales from Hog Ranch (2004). At this time, Nejma and Peter Beard set about the task of securing Beard’s legacy and harnessing the rise in market values of contemporary photography. They set up the Peter Beard Studio in 2000, creating an exemplary, informative website.

In 2006, a large-format composite volume, Peter Beard, was published in an art edition and collector’s edition. Beard’s collages were reproduced as a group for the first time at the size they were meant to be seen. Hundreds of smaller-scale works and diaries were magnified to show the detail of Beard’s handwriting and drawings, as well as stones, bones and bits of animals pasted to the page. The latest, trilingual, trade edition of the volume was published in May 2020.

Beard was a free spirit, sometimes out of control, often exasperating, but never dull. For his fellow photographer David Bailey, he was “a unique, modern man, not seen since the likes of the 19th-century explorer Richard Burton”. He had been suffering from dementia and went missing nearly three weeks before he was found dead near his home at Montauk.

• Peter Beard, born 22 January 1938, died around 31 March/1 April 2020