Gillian Wilson was one of the most colourful and effective museum curators of her generation. She was essentially self-taught, defying the orthodoxy that you must have at least a degree to be able to approach art professionally, yet she put together a collection of French 17th and 18th-century decorative art for the J. Paul Getty Museum of a quality that equals the Wallace Collection, the Metropolitan Museum, the Louvre and the British royal collection.

She was born in England to Margaret and Philip Wilson in 1941, the youngest of three children. It was a middle-class family, but life became difficult when the father moved out. As a student at Hornsey College of Art, she got the Rolling Stones to perform at the Christmas dance. Fearlessness was one of her characteristics, and she had simply gone up to Mick Jagger when the Stones were playing at the Marquee Club and offered him 15 shillings (75p) a head. They came, played for four hours, and she went on to have a fling with Charlie Watts, the drummer, whom she used to remember fondly.

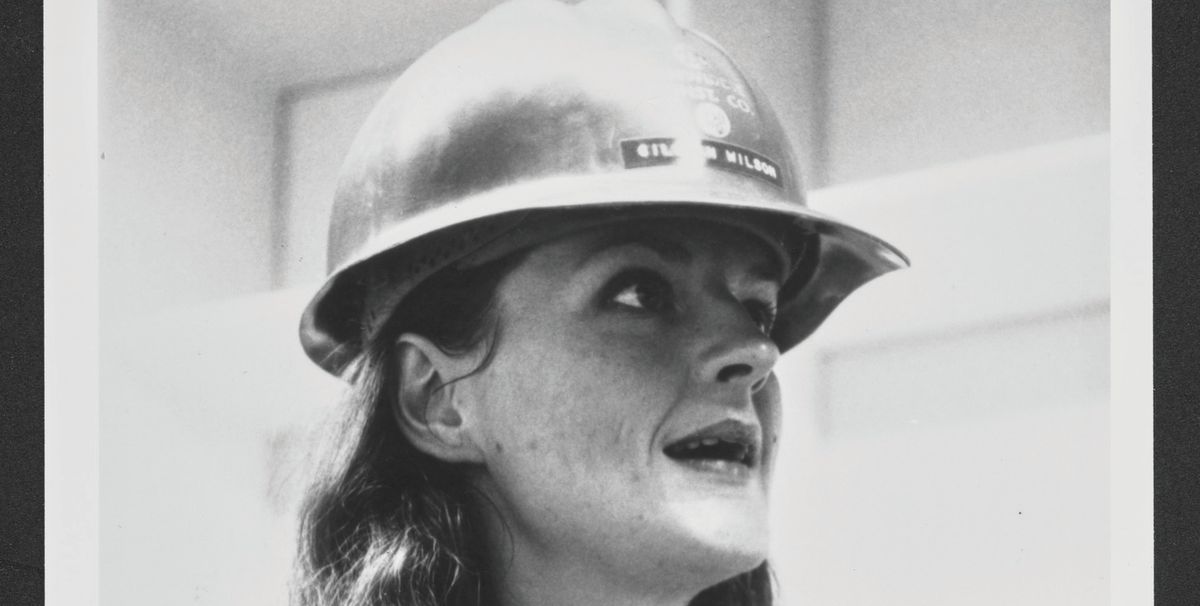

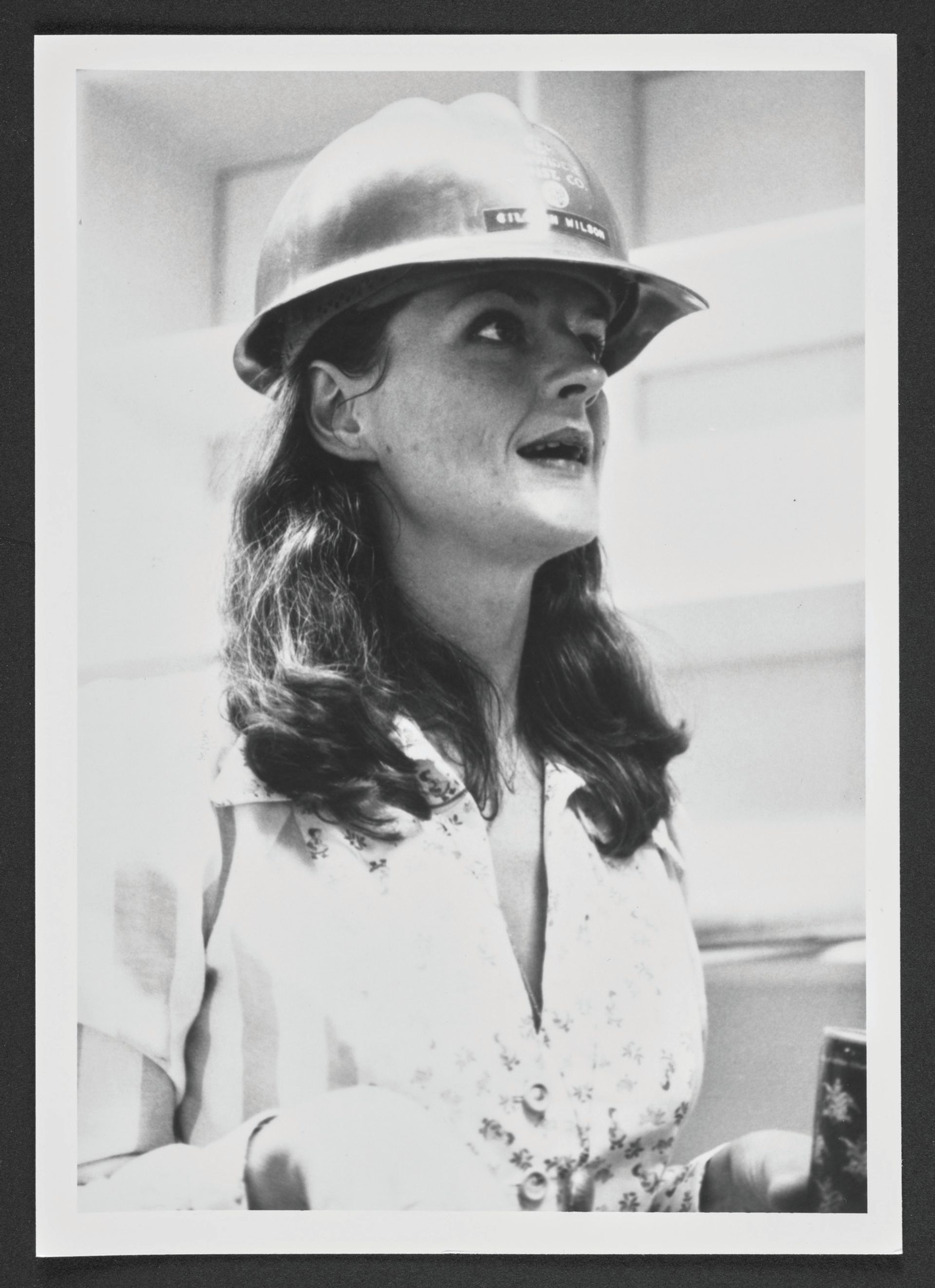

Inspirer, teacher and life-enhancer: "Miss Wilson of the Getty" Courtesy of the the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

To the end, Gillian was a great anecdotalist, but anecdotes also accumulated about her because she was so atypical of the often bland museum world. One was that she had been a stripper, when, as she pointed out, she had merely worked as a slave girl in a fur tunic in the Roman Room beneath El Cubano restaurant, where she used to be photographed with the crooks from the East End of London.

She joined the textile conservation department of the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1964, and moved to furniture and woodwork, then entering its influential years in the field of country house studies. Every weekend she visited stately homes with her colleague John Hardy, going beyond the ropes, honing her eye by close study of the furniture.

The Getty pig—table or knees?

In 1970, a fellowship took her to the Metropolitan Museum, New York, where she found the models of a prominent French faker of gilt-bronze mounts. The detailed study she made of them was to stand her in good stead when, in 1971, Burton Fredericksen, curator of paintings at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu, offered her the job of curator of decorative arts, with the remit of building up the collection of French furniture, which was one of J. Paul Getty’s interests. At the time, the Roman Villa museum was only half built, the collection, which often had no visitors at all, was housed in the Getty Ranch, and the staff worked in a trailer. But there was a lot of money to spend.

Mr Getty lived in Sutton Place, 30 miles outside London, and never came to California, so the curators used to go to him there, usually late at night, and pitched for works of art they thought he should buy.

One of her stories was how he would say, “Sit on the pig, dear” pointing at the large leather animal. She said, “If he put the photo of the work down on the table, you knew there was no hope. If it was on his knees, it was a maybe, but you needed his ‘OK, JPG’ on the margin for confirmation. He liked big, and you had to have agreed a little leeway with the dealer over the price so that he could feel he’d got a bargain”. She established a good rapport with this lonely, driven, old man and, loyalty being another of her characteristics, always spoke of him with affection.

Over the next 20 years, Gillian’s European friends got used to her coming over on buying sprees, nearly always accompanied by young research assistants who would literally be her bag-carriers. In exchange, they got deep training in connoisseurship and how to behave with politesse but firmness with the dealers. She derived huge amusement from the effect her Getty visiting card had in Paris and resisted all blandishments, “wrapping her cloak of virtue around her”, as she put it (the proof of her incorruptibility being that to the end she lived very simply in a small bungalow in Venice, CA).

Connoisseurship, cash and the collection

By contrast, for the museum she was buying the most splendid furniture and porcelain, often of French royal origin. Among the many important acquisitions she made were the Boulle cabinet bought in 1977, the Sèvres pot-pourri vases from the garniture of madame de Pompadour (1978), the comte de Toulouse’s Beauvais tapestry series of the Emperor of China, madame de Montespan’s ivory writing table (1983), three Sèvres porcelain vases from Louis XVI’s library garniture in Versailles (1984), the Ledoux panelled room (1998) and the Dubois corner cupboard at the Wildenstein-Akram Ojjeh sale, for which the museum paid a world-record price. Her reputation as a true connoisseur with a taste for the exceptional, combined with the Getty money, introduced her to a wide range of sources and retired Parisian dealers whose careers had started in the 1930s. Dealers habitually hoard great objects until late in their retirement and Gillian was able to gather them in for the museum.

The French museum curators, who then had great powers over the granting of export licences, also respected her, so unofficial negotiations were possible. Adrian Sassoon, her bag-carrier of the time, remembers, “One day in 1982 or 1983 the chief curator of the Louvre telephoned: ‘Dear Gillian, we are very keen to purchase the Marie-Antoinette piece at auction this week in Zurich. I have here the export license application for the very important piece of furniture you want to purchase in Paris. Can we come to an understanding?’ ‘Of course, we can, etc…’ She turns to me and asks, ‘What Marie-Antoinette piece is being sold in Zurich this week?’ We hadn’t a clue. It was a small, precious, agate and gilt-bronze urn that the Louvre did indeed purchase and Gillian got her export licence.”

Gillian identified passionately with the museum and all its staff, from the director to the gardeners. It was her family, her raison-d’être, something to be intensely proud of and to defend. This led to her talking about it in a proprietorial way. She would say of her acquisitions, “Mine is so much better than the one at Versailles” or, “The Queen’s hasn’t got its original top while mine has”. In the late 70s she gave one of her many lectures about the collection and the then director Stephen Garrett sent her a letter he had received from the public. “How kind of Mr Getty to buy all this furniture for Miss Wilson”, said one of them.

But she also wanted the best scholars, among them Francis Watson, former director of the Wallace Collection, and Pierre Verlet, the curator-in-chief at the Louvre, to come and share their knowledge,and invited emerging talent from across the US and Europe.

Decline and death

Getty died in 1976, unexpectedly leaving his fortune to the museum, but it was too much money for a small institution to be allowed to administer, and power slipped away from it to the new trustees, who conceived a multi-institutional cultural campus by Richard Meier up on the hill above Los Angeles, of which the museum would be only a part. The construction was so expensive that Gillian found herself with less money to spend and purchases dwindled after 1990. The management style changed to become more corporate, with a board that at one point did not include a single trustee with any knowledge of the world of art and scholarship.

The museum moved to the new Getty Center in 1997 and Gillian, alone of all departments, managed to override its minimalist design and employed the interior architect Thierry Despont to create rooms more suited to grand French decorative arts. By this time, art-history academe had turned away from connoisseurship and towards theorists such as Jacques Derrida and Jean Baudrillard. Gillian, who never saw herself as an intellectual, refused even to pay lip-service to this approach, so gradually, as it was decided that the French furniture collection was more or less complete, her role as a supremely qualified collector diminished. Her forthright British manner and the fact that she was not academically qualified began to count against her and in 2003, after 32 years, she was eased out.

Always a smoker (at the Getty Villa opening in 1974 she wore brilliant green and her cigarettes were green Sobranies), she suffered declining health, her eyesight faded, and in 2014 she had a stroke from which she never fully recovered. Friends from the old days in Europe and the US remained faithful, but the great Getty Center on the hill forgot about her, unaware perhaps that for 20 years, the 1970s and 80s, “Miss Wilson of the Getty” had been its best ambassador abroad. Above all, she was an inspirer, teacher and life-enhancer.

The French government showed its appreciation by making her a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 1988. She never married and is survived by a nephew and niece.

Three highlights of her publications are French Eighteenth-Century Clocks in the J. Paul Getty Museum (1976, 1996); Mounted Oriental Porcelain (1982, 1999); French Furniture and Gilt Bronzes: Baroque and Régence Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection (with Charissa Bremer-David, Arlen Heginbotham, Jeffrey Weaver and Brian Considine, 2008).

There will be a commemoration of Gillian Wilson at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, with a lecture about her life and work by Anna Somers Cocks, founder editor of The Art Newspaper, followed by a reception, on 22 June 2020 at 18.30. For more details, contact Deborah Gage (debo@deborahgage.com).

• Gillian Wilson, born 26 November 1941, died 15 November 2019