You can always tell a true believer from a grazer in the art world. The more bewildering a work of art, the more it appeals to the faithful. Mystification creates intrigue, stirs debate. Browsers go more for selfie ops.

Head-scratching pleasure won the day among the artists and curators who flocked to the 2 November opening of a collaborative exhibition of complementary works by Liam Gillick and Adam Pendleton—two conceptual artists who would seem to have no connection other than their affiliation with Galerie Eva Presenhuber in Zurich. (Each is associated primarily with other dealers in New York.) This show revealed a shared compulsion to collate, and to baffle.

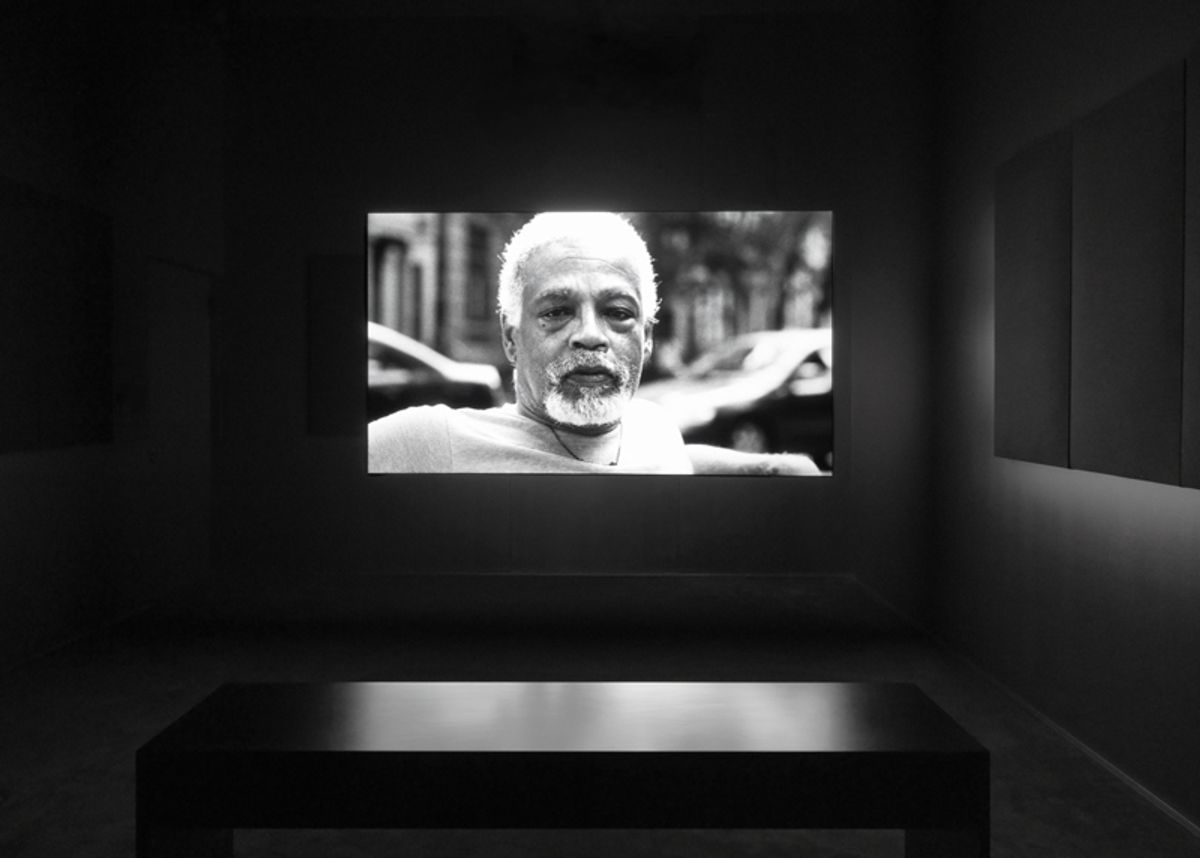

Visitors started out in the dark. Plunged into the blackest of black boxes just inside the gallery door, they were confronted by the premiere of Pendleton latest video portrait—a tender study of the dancer/choreographer Ishmael Houston-Jones. (Yvonne Ranier was the focus of his previous film.)

Intimacy doesn’t begin to describe how close Pendleton brings viewers to his subject, who speaks both in voice-over and directly to the camera about his family, a sexual encounter, and deep personal losses of a sort that everyone will recognise. It’s intense.

After this, moving into the blinding light of Presenhuber’s exhibition space was quite disorienting. It took a minute to register the works, which face off on opposite sides of the room and stick to black and white.

But what is? Gillick’s salon arrangement of prints, in several sizes, picturing texts distilled from uncredited sources went for the grey areas. “It’s a compilation,” he said, a kind of anthology of economic, social and philosophical influences on his thinking. “Our ideas are fragmented—events in the day—deconstructed and recomposed,” he’d written in a press release. “They take place alongside everything else.” This helped to explain the installation but otherwise left me none the wiser. “It’s about irony and disorder,” he told me. It felt vaguely political.

Installation view of Liam Gillick, Adam Pendleton, at Eva Presenhuber, New York, until 22 December 2018

“Do you know what’s going on here?” asked Kathy Halbreich, who was enjoying her first, full, post-MoMA day as director of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. We stared at Gillick’s prints and took in the adjacent walls that Pendleton had covered in black-and-white wallpaper blasted with spray-painted graffiti spelling "Crazy Nigger". On top of that are framed, black-and-white images of a scribbled-over mask, a vase, and a Sol LeWitt cube, among others from a personal lexicon that Pendleton calls Black Dada.

“It’s a way to answer the question, what does Black Dada look like and what does it do?” Pendleton said of his display. What it did here was connect disparate objects and ideas that have meaning for the artist. This I understood, because I’d heard him explain Black Dada previously as, “a way to talk about the future while talking about the past.” I’d also read the volume of essays and poetry by himself and many others that he published under the title, Black Dada: What Can Black Dada Do for Me Do for Me Black Dada, a Reader.

It’s really a manifesto. Who bothers with manifestoes anymore? You gotta love a guy who dares. This particular guy has many admirers, including the Performa biennial founder RoseLee Goldberg, the Whitney Museum curator Adrienne Edwards, the writer Lynne Tillman and the artist Joan Jonas, all present at the opening.

“Who are these other people?” asked Jonas, who will be the next to go in front of Pendleton's camera. “I don’t recognise half the faces here.”

We departed as we arrived, still in the dark. Though we are New Yorkers, suddenly we couldn’t work out which direction was up, down, east or west.

You gotta love a show so confounding that your own home feels foreign. Black Dada!

• Liam Gillick, Adam Pendleton, at Eva Presenhuber, New York, until 22 December 2018