History repeats. Right? If any proof were needed, the Met Breuer has it in abundant supply. Though conceived nearly a decade ago by Douglas Eklund, a photography curator for the Metropolitan Museum, Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy has arrived in New York during the tenure of the most conspiracy-crazed president yet to occupy the Oval Office. Is that a coincidence? Or have I internalised the contents of this cautionary show?

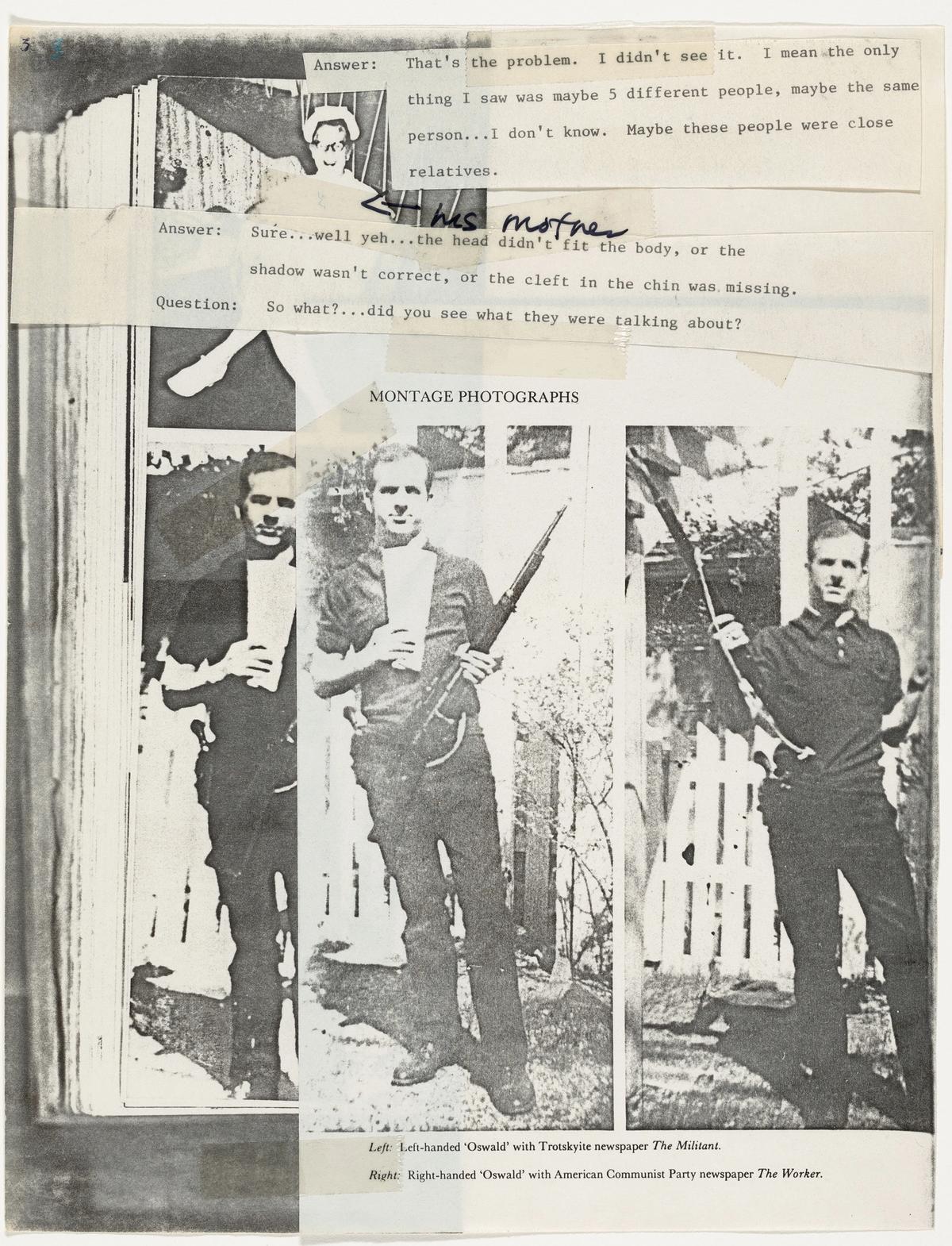

As Ian Alteveer, the exhibition’s co-curator, remarked at the exhibition’s packed opening that conspiracy theories have been a substream of American political life since the assassination of John. F. Kennedy in 1963. What Everything’s Connected makes clear is how much contemporary artists have contributed to them.

Contemporary artists tend to treat certain authorities as a threat to free expression and personal liberty, among other principles of democratic rule. As private citizens, many have committed themselves to exposing the covert means and methods by which paranoid prevaricators in government, industry and finance have abused their power over the public and the popular media (their sometimes unwitting accomplice).

The 70 works in Everything’s Connected identify or decode suspicious links between colluding forces of the last 50 years, pinpoint the consequences of their acts, and then imagine the kind of world that may be waiting if we let them get away with it.

Some of the works on view are by what we might call the usual suspects of politically attuned artists, but they belong in a show like this. “I really do,” agreed Peter Saul, whose 1969 painting, Government of California, is a nightmarish landscape of death-dealing monsters led by a red-faced Ronald Reagan challenged by a knife-wielding angel with the face of Martin Luther King, Jr.

No president is safe from artists here, nor should any be. Think of Richard Nixon and his Dr Strangelove, Henry Kissinger, whose social relations with foreign dictators like the murderous Augusto Pinochet became something of an obsession for the Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar. The late Mark Lombardi’s genealogical flow charts of interlocking power networks are also here, along with Lutz Bacher’s steely subversion of a smear campaign and photographs by Trevor Paglen that pinpoint CIA “black sites” for illegal torture, which were invisible to the naked eye but not to his telescopic lens.

The appalling lapses in moral and civil authority that the works here bring to light don’t just qualify as nonviolent protest but also concern the effects of the events that inspired them on generations born to a different reality. In her room-size installation, Snake in the Grass (1997), Rachel Harrison chose photographs depicting the souvenir stand that the grassy knoll in Dallas became after Kennedy was shot there and mounted them on pieces of freestanding drywall. They form a maze evoking the dead ends and obstructed views of investigations that fueled the Internet-dispersing conspiracy nuts of the present. “It’s all about the frame,” she explained to Max Hollein, the Met director, “and what lies outside the frame.”

Presumably, that would be us.

• Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy, the Met Breuer, until 6 January 2019