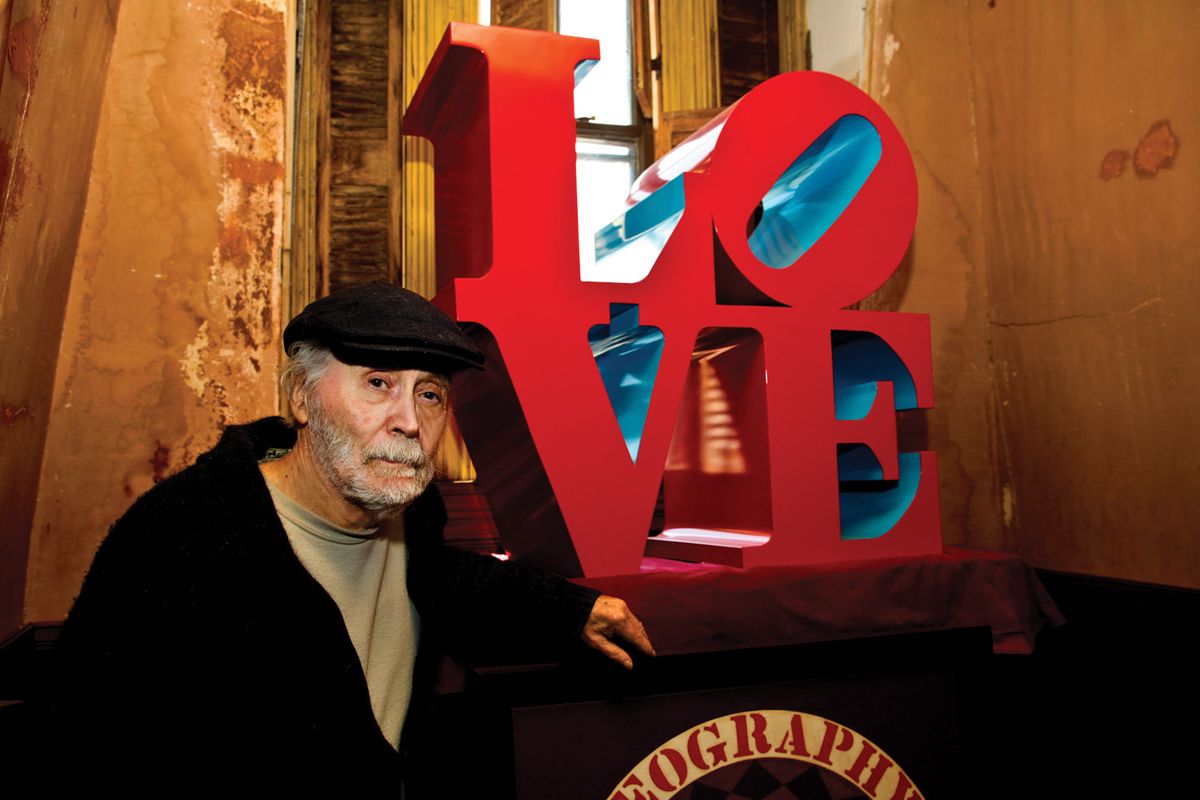

What will become of Robert Indiana’s legacy, and who will be in charge of preserving it? The answer might only come out of a closely-watched legal battle over the artist’s estate and his recent output, which started the day before Indiana’s death on 19 May, aged 89, and looks set to heat up this summer.

In June, the Maine Attorney General’s Office announced that it would be monitoring the case, which has its first pre-trial hearing in a Manhattan district court on 23 July. Meanwhile, the lawyer representing Indiana’s estate—estimated to be worth $50m—is seeking documents to determine the extent of the artist’s assets, based on “reasonable suspicion” that some “may have been conveyed away or otherwise misappropriated or sold without due compensation”, according to probate court filings in Knox County, Maine.

No love lost

In May the Morgan Art Foundation (MAF), Indiana’s representative since the 1990s and the owner of the artist’s famous Love trademark, filed a lawsuit in New York against the artist’s long-time assistant, Jamie Thomas, and an art publisher, Michael McKenzie. MAF says the pair exploited Indiana towards the end of his life, producing dubious works in his name and isolating him from friends. It is also challenging Indiana’s will, signed and dated 7 May 2016, which gives Thomas power of attorney and names him as the executive director of a museum the artist intended to be established at his home and studio on the island of Vinalhaven, 15 miles off the coast of Maine.

According to the will, a non-profit organisation The Star of Hope, named after the rambling 19th-century building that Indiana made his home in 1978, is to be used “for the continued preservation, promotion, exhibition and use of my collection and real estate”. Indiana stipulated that his foundation is to be the recipient of any royalties from his art. But Luke Nikas, the lawyer representing MAF, says Thomas is not qualified to direct such a museum. Instead, he suggests a “diverse board” of specialists should manage it and protect Indiana’s legacy and market (MAF is currently working on Indiana’s catalogue raisonné).

Lukas’s recommendations include the collector and curator John Wilmerding, the New York gallerist Paul Kasmin and representatives at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, which staged Indiana’s retrospective in 2013, as well as the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine.

No formal list has been drawn up, but Nikas believes there would be “significant support” for the idea. “These are people who have been part of Indiana’s life for a long time I would expect that many, if not all of them, would be willing to support the foundation through either an advisory or board position.”

Christopher Brownawell, the director of the Farnsworth, says he has not “discussed in detail” the MAF proposal but says “it would be of great benefit to assemble a significant group of people with that level of experience who would approach it with the common goal that they’re in the business to promote and preserve Bob’s legacy”.

Loyal supporter

The Farnsworth has long-supported Indiana, organising a major survey in 2009—the same year his illuminated sculpture EAT was first installed on the museum’s roof. In 2012, Indiana told The Art Newspaper that the Farnsworth would probably inherit his collection. “We are uniquely equipped to preserve and promote his legacy and his important contributions to American art,” Brownawell says. “If the time arises, we will certainly be ready, willing and able to assist.”

McKenzie says that the lawsuit is simply “a frivolous attempt” to discredit Thomas, whom the publisher describes as “Bob’s best friend and studio assistant, who painted for him for many years”. The defendants have yet to file a response in court, although McKenzie strongly refutes the allegations and told The New York Times that he and Thomas were only following Indiana’s wishes. Thomas could not be reached for comment. The first pre-trial hearing in Manhattan is scheduled for 23 July.

Meanwhile, Thomas, McKenzie and representatives of MAF, including its long-time consultant Simon Salama-Caro, who is editing the artist’s catalogue raisonné, have been ordered to appear in court in Rockland, Maine, on 18 August to provide information about the assets in Indiana’s estate. The lawyer representing the estate, James Brannan, says he believes that Thomas and McKenzie had sold works by—or “derivative of”—Indiana without properly compensating him, citing the New York lawsuit.

Brannan also suspects that MAF may have not paid the artist what it owed him before his death, and that it has not provided proof of ownership of certain works it has demanded from the estate. At the end of June, the office of Maine’s attorney general, Janet Mills, said it would be monitoring the dispersal of Indiana’s estate, as part of its responsibility to “enforce gifts to charities”.