I am in the final stages of filming three new episodes of Britain’s Lost Masterpieces for the BBC. The series investigates three unattributed pictures in museums to see if we can identify who painted them. This year we have set ourselves an almost impossible challenge with two of the biggest names in art history (although I’m afraid I cannot tell you who they are yet). After many months, the pictures are nearing completion in the conservation studio. The research is done. The technical analysis is in. Now we are just awaiting the verdicts of the relevant experts. I don’t mind admitting it, I’m nervous.

The bigger the name of the artist, the worse the politics. Usually, the reception to new attributions broadcast on Britain’s Lost Masterpieces is positive. Even among doubters there is an enthusiasm to debate the evidence. But there is always one person who takes things to a more militant level, and I’ve noticed a pattern; they are male, and elderly. They never ask me about the paintings or the evidence. They simply want to shout “You’re wrong!” as loudly as possible.

When I was in the art trade, I used to assume that some scholars’ disdain for new discoveries was due to the financial implications of an attribution. But in Britain’s Lost Masterpieces we never discuss value, and only ever deal with publicly owned paintings that cannot be sold. I now realise that some scholars are driven by nothing more than a desire to retain control over ‘their’ artist. It’s not about the art, it’s about authority.

Nonetheless, it is almost impossible to separate value from attribution. People always ask: “What’s it worth?” Earlier this month I was asked to comment on the forthcoming sale of a Rubens in London, a portrait of his daughter Clara Serena (1623). We’ve known for some time now that New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art sold the picture by mistake in 2013, when it was deaccessioned as a copy with an estimate of just $20,000 to $30,000. It has been exhibited widely as a Rubens since then. But it was only when Christie’s announced that the picture would carry an estimate of £3m to £5m that the story really became news. For what it’s worth, I think the estimate is probably on the low side; Clara Serena is captivatingly painted by her father in a way that will resonate with parents the world over. She may break records.

Grim humanity

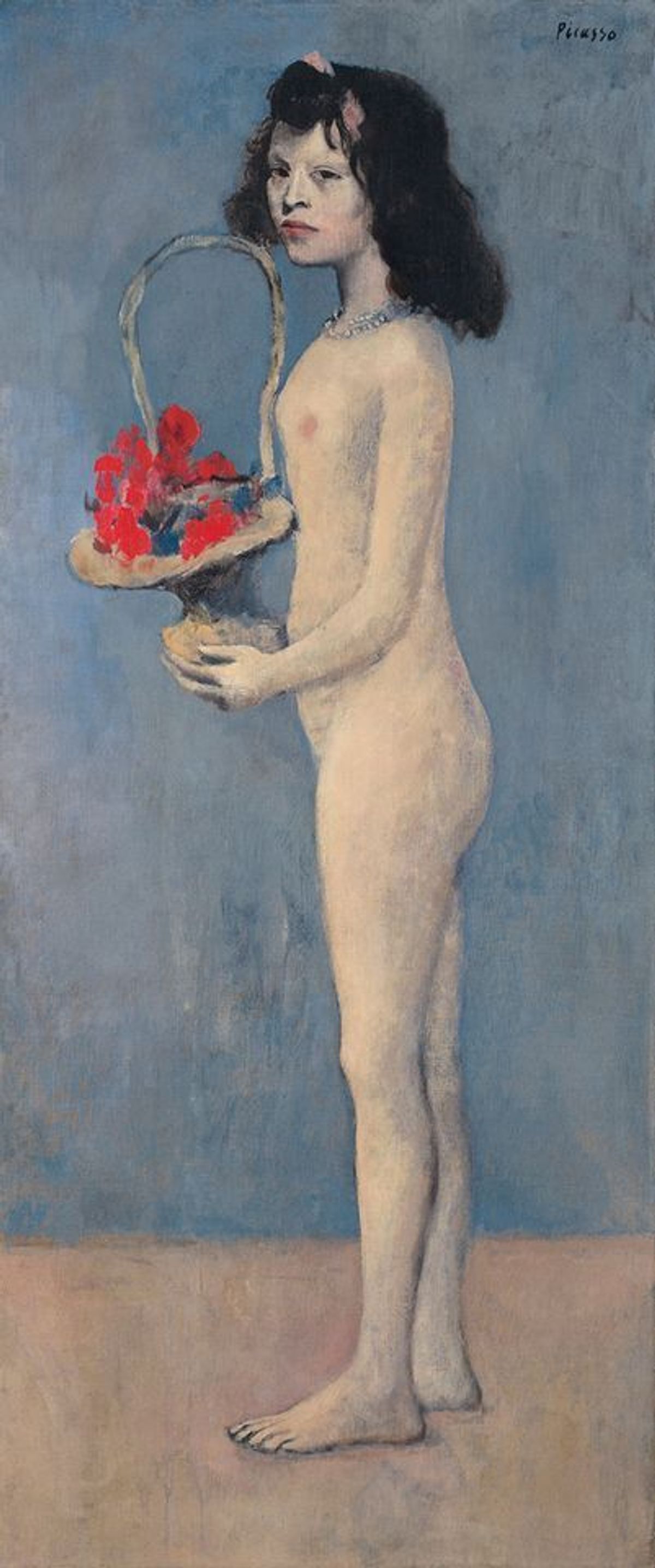

Of course, a painting’s value usually says more about us than the art. If so, what should we make of Picasso’s full-length nude, Young Girl with a Flower Basket (1905), which made $115m at Christie’s sale of the Rockefeller Collection in New York? The painting was heralded as a masterpiece that “defines humanity”. But what a grim humanity. The girl, as the catalogue entry eventually and hesitatingly made clear in the 15th paragraph, was a child prostitute. Given what we know of Picasso’s proclivities with prostitutes, she—Linda is all we know of her name—was very likely one he slept with. Yet a pretence is created that in painting her Picasso was a disinterested, compassionate observer of her plight, which in turn validates our dehumanising dissection of his victim.

Neither art history nor the art market have really begun to tackle the issues around pictures like this. The same subject through the eyes of most other artists, and indeed most other mediums, would be thought barely fit for display, let alone scholarly adulation and a $115m price tag. I’m not in favour of judging the past by contemporary standards, but we allow art to cleanse even the worst crimes. We shouldn’t.