Jill Magid does not do anything halfway. The US artist, who has had solo shows at Tate Modern in London and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, is known for research-intensive projects that can take years to complete. She has exhumed the ashes of the Pritzker Prize-winning Mexican architect Luis Barragán, submitted herself to near-constant surveillance by police and signed a contract to turn her own ashes into a diamond. Magid immerses herself in bureaucratic institutions, such as the Dutch secret service and the New York Police Department, to reveal the humanity beneath authority. Roberta Smith wrote that her work “seems motivated by an urge to infiltrate and personalise, if not sexualise” systems of power. For her latest project, Magid has turned her attention to the bureaucracy surrounding the legacy of Luis Barragán.

At Art Basel in Miami Beach, the Mexico City-based gallery Labor presents works from her Barragán project, which is also the subject of a documentary co-produced by Laura Poitras that is due to be released this spring. We spoke to Magid last month in her Brooklyn studio, a walk-up stuffed with file boxes and newspaper clippings.

• Artist Talk, Jill Magid, Pamela Echeverría and Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, Miami Beach Convention Center, Sunday 4 December, 10am

The Art Newspaper: You became interested in Barragán because of the fate of his archive, half of which is stored in Switzerland and nearly impossible for the public to access. Why choose this subject?

Jill Magid: It ties into my concerns about legacy, power, access, copyright and the law. The personal archive is at Casa Barragán, the architect’s former home in Mexico. The professional archive was purchased by the head of the Swiss furniture company Vitra, and is stored in a country that has none of his architecture. The idea of having a personal side and a professional side to a legacy is fascinating. What does it mean to own the rights to Barragán’s work? Does it mean you own the actual architecture in Mexico? Does it mean you own all reproductions of it?

How did those questions inspire your work?

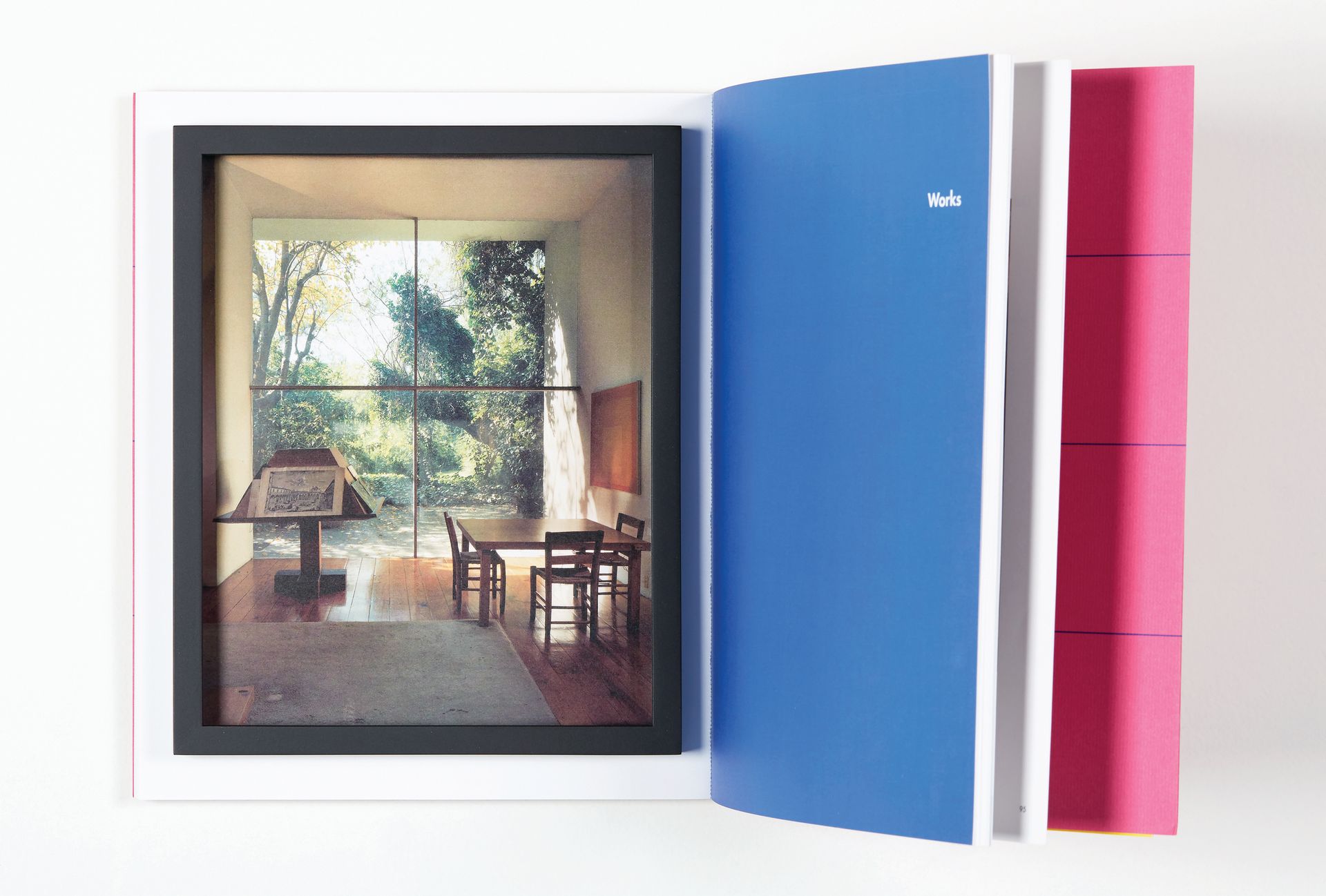

The works I made are physical manifestations of those questions. The Barragan Foundation said I could not reproduce anything from the archive without legal consequences. That challenge led to some amazing forms. Rather than reproduce images from a book on Barragán, for example, we framed a copy of the book itself as a readymade. There’s a kind of poetry that arises out of pragmatism.

You got permission from both the Mexican government and Barragán’s family to exhume his ashes and have them made into a diamond. Why do that?

As the story goes, the head of Vitra bought the archive as a wedding present in lieu of an engagement ring for his wife [the architectural historian Federica Zanco]. The story made me think about the archive itself as a kind of lover. It was this engagement between multiple people: the architect, the chairman of a corporation, his wife and the public.

In May, you “proposed” to Zanco with the diamond made from Barragán’s remains. If she accepts your proposal, she must return the archive to Mexico. Has she decided?

There hasn’t been an outright yes or no, but I didn’t expect to get one right away. It was very important to me when we were negotiating with the family that there wasn’t a deadline [for Zanco’s response]. I think of movies where a man proposes to a woman and waits under her window for years. It’s a committed, romantic gesture. The ring is a gift, and it is meant to inspire a gift in turn. It’s the body of the artist for the body of work.

Your work often reveals the absurdity of bureaucracy. In 2002, the Amsterdam Police Department rejected your offer to bedazzle their security cameras, saying they don’t work with artists. When you returned with a business card for an invented company called System Azure Security Ornamentation, they changed their minds.

They were on board because I spoke their language. I wouldn’t get so deeply into these projects if I didn’t realise their complexity or respect the institutions. This is not satire; anyone who has worked with me has seen my perseverance and sincere desire to learn. The idea is to gain permission as a material of the work.

How do you convince these secretive organisations to give you access?

In Evidence Locker [a project of films created from CCTV footage of Magid obtained by the Liverpool police], I simply filled out the forms that were available. The fact that I was the first person in three years to fill out those forms shows you that there are ways to engage with these systems, but they are hard to find, or people aren’t interested, or they don’t think it will lead anywhere.

Your interactions with the police ended up being quite intimate.

I decided to fill out the forms like diary entries or love letters—I gave the police everything they needed, but also everything I was feeling, everything I smelled. What I never imagined is that they would get so into it. I would walk down the street and every surveillance camera would turn to look at me. I learned more about the CCTV system in 31 days than most people learn in years. I was asked to speak at surveillance conferences all over the world. It’s amazing how much you can learn when a relationship is formed.

Art that questions authority

Facistol (2013)

At Art Basel in Miami Beach, Labor will present, among other works, this reproduction of a pine lectern that Magid saw in Barragán’s Mexico City home. Although she is permitted to show her copy in the US, where it is protected by the fair-use doctrine, she covers the work in blankets when it travels to Europe, where the unauthorised reproduction of furniture is prohibited.

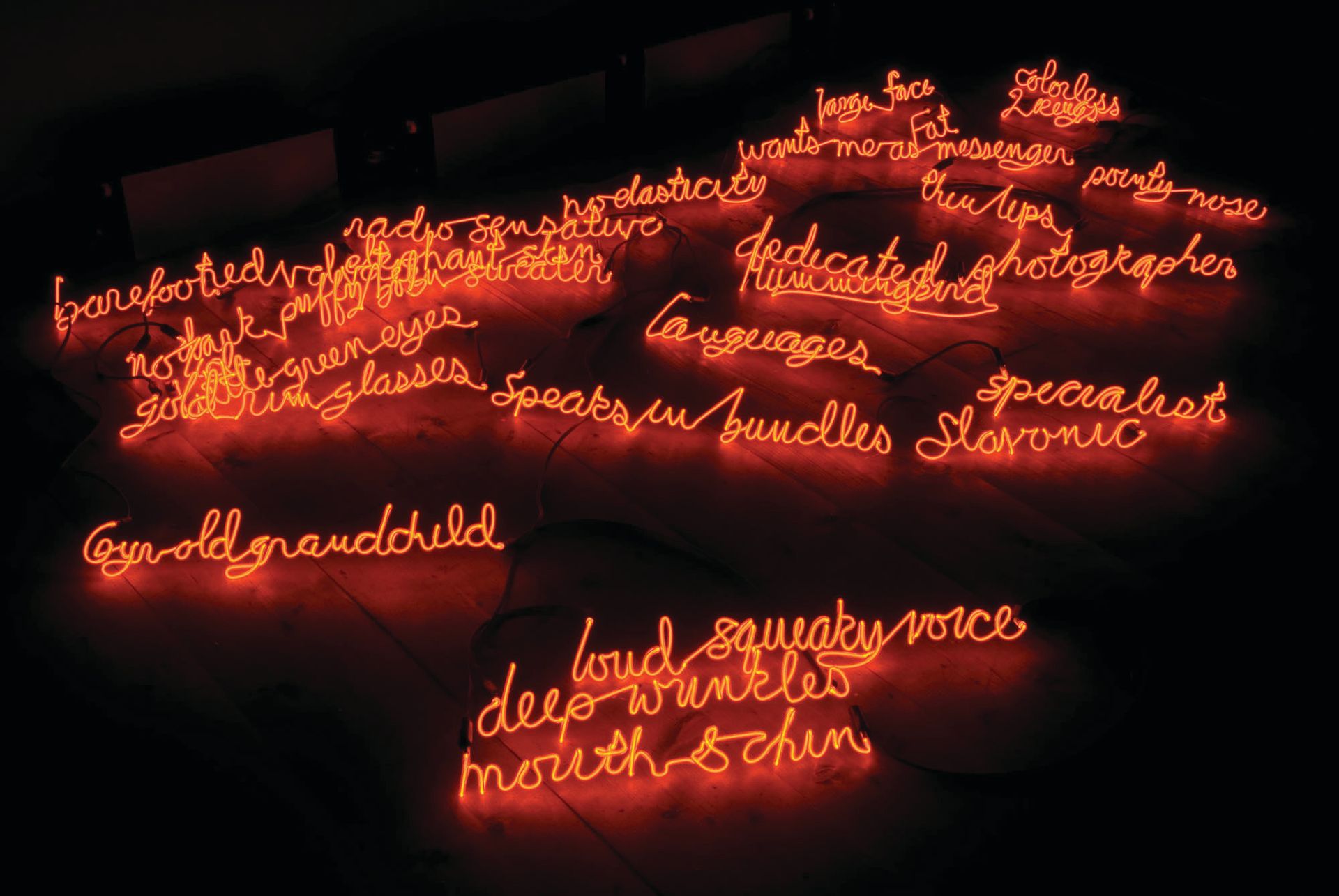

The Spy Project (2005-10)

Magid was commissioned by the Dutch secret service to make a work for its new headquarters. Over the next three years, she met with 18 employees and created a series of neon works, sculptures and drawings, as well as a book based on her conversations. The agency objected to the book but agreed to let her display it once, under glass, at Tate Modern in London. On the final day of the exhibition, agents confiscated the manuscript permanently.

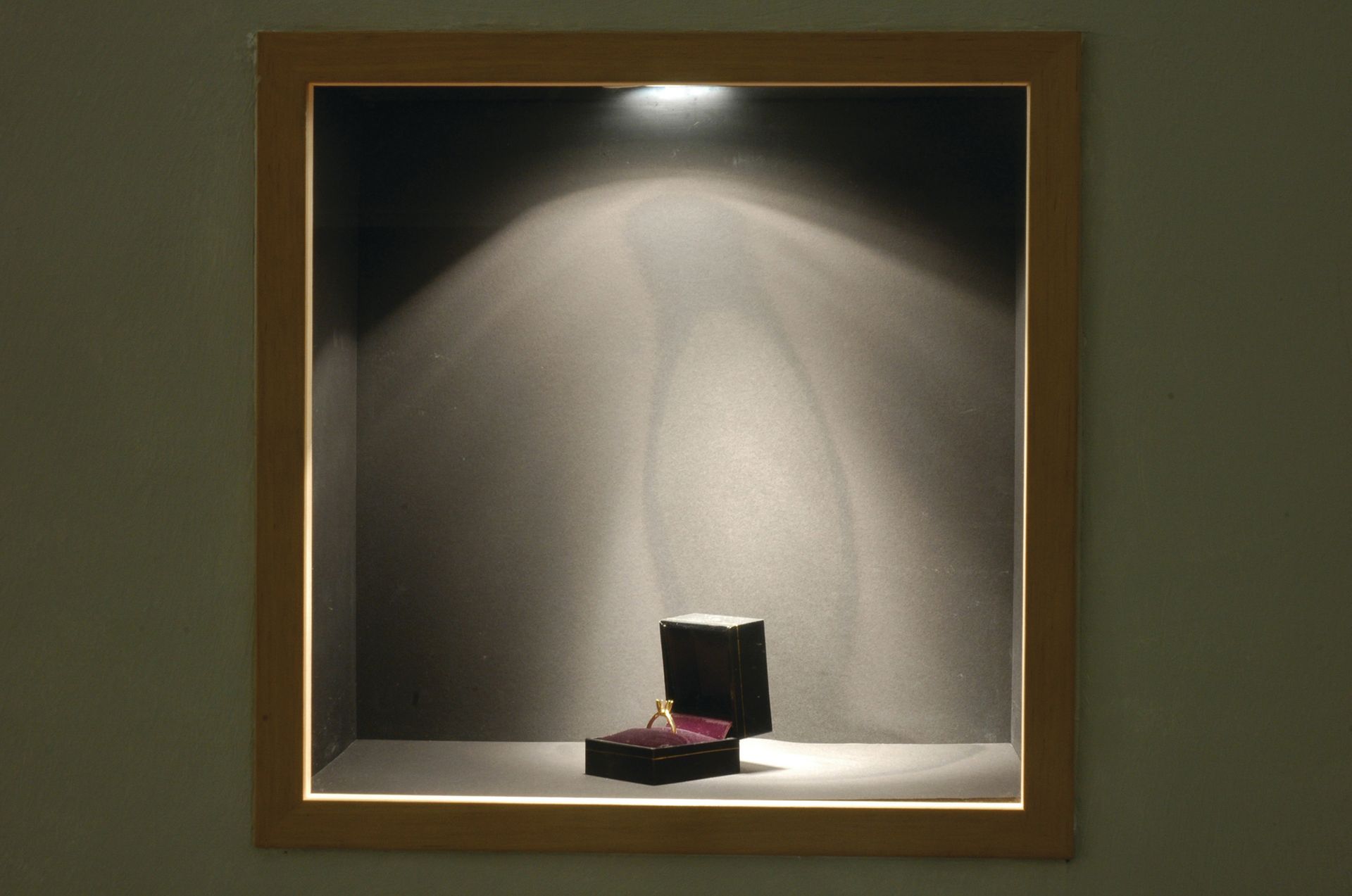

Auto Portrait Pending (2005)

Magid signed a contract with the company LifeGem to have her cremated remains turned into a diamond. Until her death, the work comprises an empty ring setting and a set of contracts. “The piece will eventually be bought by a collector, and when I die, the diamond will be delivered,” Magid says. “The concept raises so many questions about the body of the artist as commodity fetish.”