When Robert Rauschenberg arrived on the tiny island of Captiva, Florida, in 1970, he was worn out by life in New York. His star turn in the 1964 Venice Biennale made him famous. But he was lonely, depressed and drinking much more than he was working. “Everything was falling apart,” he said in a later interview. “There was such an abundance of bad news.”

As Calvin Tomkins wrote in the book Off the Wall: A Portrait of Robert Rauschenberg, “the critical rap is that he stopped breaking new ground around 1965”, well before he moved permanently to Florida. But a survey opening this week at Tate Modern in London (1 December-2 April) seeks to disprove that assumption.

The show, which travels to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2017, re-examines the artist’s oeuvre. Curators draw a straight line between Rauschenberg’s early work and the art he made in Captiva, his home from 1970 until his death in 2008. Both bodies of work have been overshadowed by the muscular combines, his best-known works. But they illustrate his lifelong commitment to redefining painting.

“The foundation of my work”

Was a postcard-perfect island—just over one square mile in size, surrounded by the Gulf of Mexico—an escape hatch that revived Rauschenberg’s career? “Captiva is the foundation of my life and my work,” the artist wrote to a Florida journalist. “It is my source and reserve of my energies.”

It is not difficult to see the appeal. On a recent visit to Rauschenberg’s compound, which is now maintained by his foundation, dolphins swam just off the shoreline, grapefruit trees were heavy with fruit and seashells studded the white sand. The island has no streetlights and is home to fewer than 600 year-round residents.

This oasis must have felt especially invigorating to Rauschenberg in 1970, when the optimism of the early 1960s had been eroded by one crisis after another: the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, race riots across the country, the My Lai Massacre in Vietnam. The artist recalled feeling exhausted by the relentless focus “on world problems [and] local atrocities”. The curator Achim Borchardt-Hume, who organised the survey at Tate Modern, says: “Something was definitely coming to an end. Captiva allowed him to start again.”

Rauschenberg had begun to visit Captiva a few years earlier, but only for short spurts. Now, he settled into a house facing the beach and started drawing. “For the first time since 1964,” Tomkins wrote, “Rauschenberg was turning out a great deal of new work.”

Waste and softness Before he left New York, Rauschenberg had been spending much of his time on Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT), a foundation he co-founded to foster collaboration between artists and engineers. In Captiva, the artist yearned for something different: to work “in a material of waste and softness”, he wrote.

He began manipulating cast-off cardboard boxes into geometric wall sculptures, many of which will be included in the travelling survey. Subsequent series were inspired by his packed international travel schedule, but they were always assembled with materials that surrounded him in Florida, such as driftwood, mosquito nets and sand. “The island shifted his approach to materials and his way of working,” Mark Godfrey writes in an essay for MoMA’s catalogue.

Captiva also brought him back to basics. As a student at Black Mountain College, Rauschenberg had volunteered to collect garbage on campus, which he would often re-use in costumes. “He was always testing and combining materials in search of new possibilities,” says Leah Dickerman, who is organising the presentation at MoMA.

Over the next 35 years, as prices for his work rose, Rauschenberg became the largest private landholder on Captiva. At the time of his death, he owned more than ten buildings and a stretch of undeveloped jungle. (After Hurricane Charley charged through Florida in 2004, Rauschenberg demanded that his trees be replanted first, and any property damage could be dealt with later.) Rauschenberg assembled a cast of assistants—mostly locals who were hired after a brief conversation that convinced him they would get along—to help him take full advantage of new printing technologies. One assistant recalls the joy the artist took in calling the company Epson to ask outlandish questions, like how to print on silk.

A new generation After Rauschenberg died of heart failure in 2008, it was not difficult for the leaders of his foundation to decide what to do with Captiva. Rather than turn it into a museum, which would be impractical considering its remote location, they decided to see if its spirit of experimentation would carry over to a new generation. “We brought ten people down as a pilot programme,” says the foundation’s director Christy Maclear. “We wanted them to be inspired—but you can’t engineer that.”

At the end of the programme, the foundation asks participants if they would have preferred a $50,000 grant to their stay in Captiva. “All of them said they preferred the residency,” Maclear recalls. Since 2012, Captiva has hosted 250 residents, chosen by a rotating, anonymous selection committee. They receive a stipend, lodging in one of Rauschenberg’s buildings for five weeks and meals cooked by a chef-in-residence.

Several of the artist’s assistants remain on staff to help the residents experiment with printmaking using Rauschenberg’s own printers and presses. Carrell Courtright, a studio supervisor for the foundation, says: “We still take great pleasure in calling up Epson and stumping them.”

Art for the ears, eyes and bodyCurators pick their favourite lesser-known Rauschenberg works

Leah Dickerman, curator, Museum of Modern Art, New York

Oracle (1962-65)

You might hear this installation before you see it. Rauschenberg collaborated with a team of engineers to conceal five radios inside assemblages made from a car door, a ventilation duct and other industrial metal objects. The work uses a transistorised wireless microphone system—cutting edge for the time—to emit the steady hum of AM radio. The title, Oracle, is fitting because the work “combines cast-off parts of machines with hints of our technological future”, Dickerman says. While on display in its permanent home at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the work spouts French. During its tour to London, New York and San Francisco, it will tune into local English-language stations.

David White, senior curator, Rauschenberg Foundation

Glacier (Hoarfrost) (1974)

Rauschenberg never shied away from an experiment with new materials. He was inspired to create this series after he noticed faint traces of source images showing up on the cheesecloth used to clean his lithography stones. He aimed to capture a similar ghostly echo by transferring images from newspapers and magazines onto delicate fabric with solvent. With the slightest breeze, the fabric begins to dance. In this example, Rauschenberg goes one step further by tucking a pillow behind the fabric, a reference to one of his most famous combines, Bed (1955). “He kept finding new ways to make a painting,” White says.

Achim Borchardt-Hume, director of exhibitions, Tate Modern, London

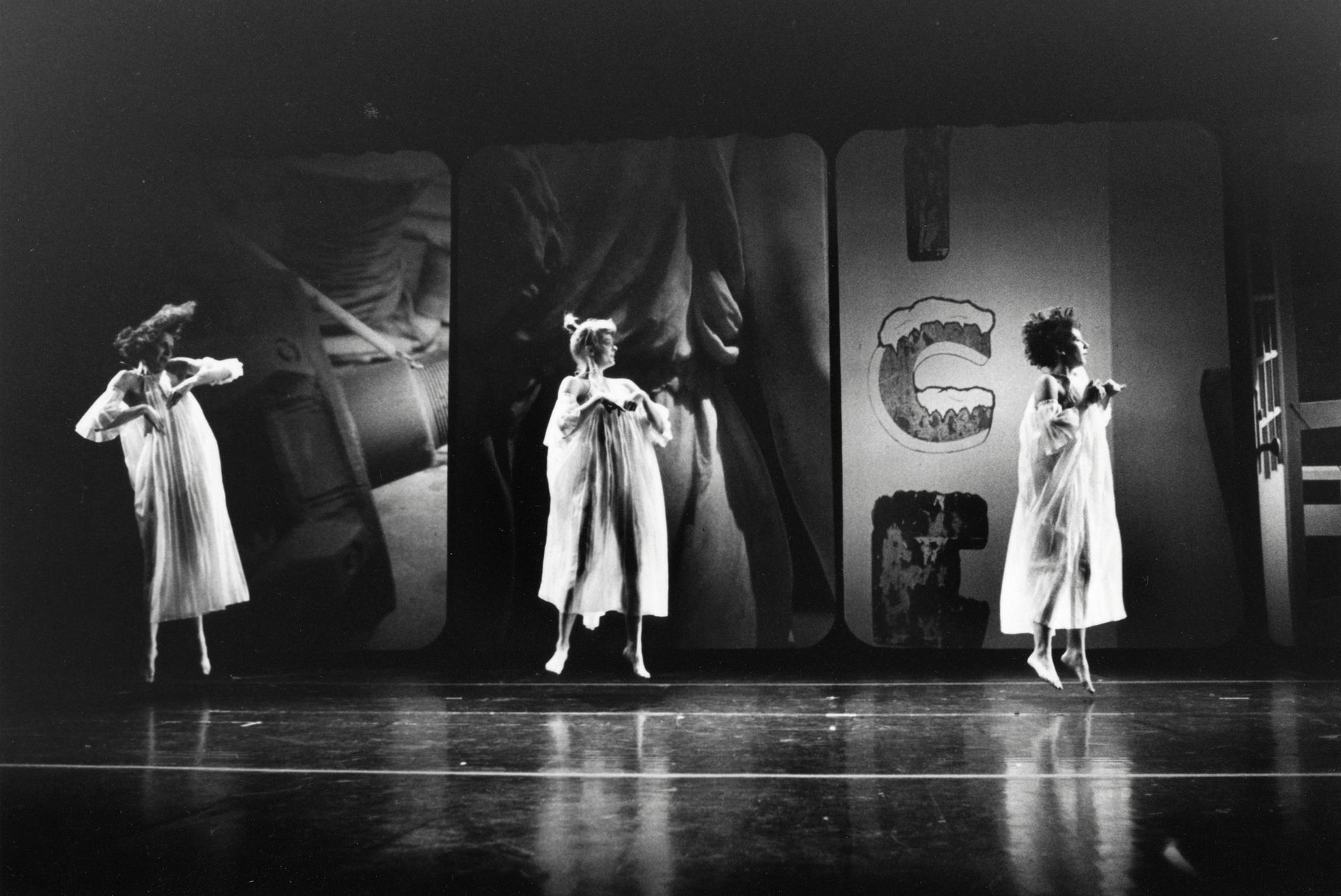

Backdrop for Glacial Decoy (1979)

From the late 1970s to the early1990s, Rauschenberg made sets for the New York-based choreographer Trisha Brown. This four-screen projection features several hundred black-and-white photographs—mostly landscapes—taken near his home in Captiva. The project marked Rauschenberg’s return to photography, a medium that fascinated him as a young artist. “As the slides fade in and out, four dancers move across the stage in such a way that you never know how many there are,” Borchardt-Hume says. “There’s no music; all you hear is the click of the slide projector.”