I wonder who’s really enjoying themselves at Art Basel in Miami Beach today. Art is supposed to enlighten, uplift, stimulate, delight, provoke or improve us. Dragging oneself around thousands of works of art in random competition with each other is the worst possible way to have any of these experiences.

Fairs coarsen my perceptions so that I end up remembering things that are either very big and red, very astonishing or very unpleasant, while refined, quiet works of art fade into the background. Imagine trying to introduce the subtle grey lines of Agnes Martin to the public at an art fair.

Besides, much contemporary art needs explaining, but you either get no explanation or a sales girl sidling up to you in department store mode, which makes me mutter, “Just looking”, and move on.

Abu Dhabi Art is quite different. I can’t think of any other fair where I’d see mega-dealer David Zwirner bending over to explain Minimalism to a seven-year old girl, as I did a few years ago there. The latest edition, from 16 to 19 November, was small (35 galleries compared to Art Dubai’s 94 and Art Basel Miami Beach’s 260 plus). The dealers who came were mostly repeat visitors who had built up a regular, faithful clientele, so there was little pressure on them and conversation flowed as a result.

Fair conversations

I had a good gossip with Michael Findlay of Acquavella Galleries, present for the fourth time, about Warhol in 1980s Italy when he was unfashionable, and about local taste and knowledge. He said, “Emiratis travel a great deal, and everyone knows Picasso and Warhol, while Basquiat has the highest recognition factor—but even someone like Wayne Thiebaud isn’t unknown”).

Had he sold, I asked (it was day three): “Not yet,” he said, “But we keep coming every year, and I can tell you that we don’t bother with places where we don’t sell”. He always brings a taster of all their holdings from the late 19th-century—a Degas this year—and Modern through to contemporary.

At Beirut’s Agial Art Gallery I had an even longer gossip with my friend Saleh Barakat, who said that the crisis had affected the big institutional sales, but that he had sold in the $15,000-20,000 bracket. He told me about the extraordinary by-blow of the Lebanese civil war, which was the three-foot tank made by Ginane Makki Bacho in her kitchen from the fragments of the bomb that destroyed her house: “It was a very personal bomb”, he said dead-pan.

Arabic calligraphy, still not collected by the Tate because they don’t consider it truly contemporary, is developing in ever more subtle and ingenious ways. He had a minimalist painting by the Lebanese art critic and poet, Samir Sayegh, that looked like just a coloured band traversing the canvas, but a flourish above and below turned it into the word hub, love.

With Robin Start of London’s Park Gallery, an old hand at the market in the region, I heard about the fakes of Middle East Modern art being made in Iraq today; journos love skulduggery so I filed this tidbit away for future use.

Local heros

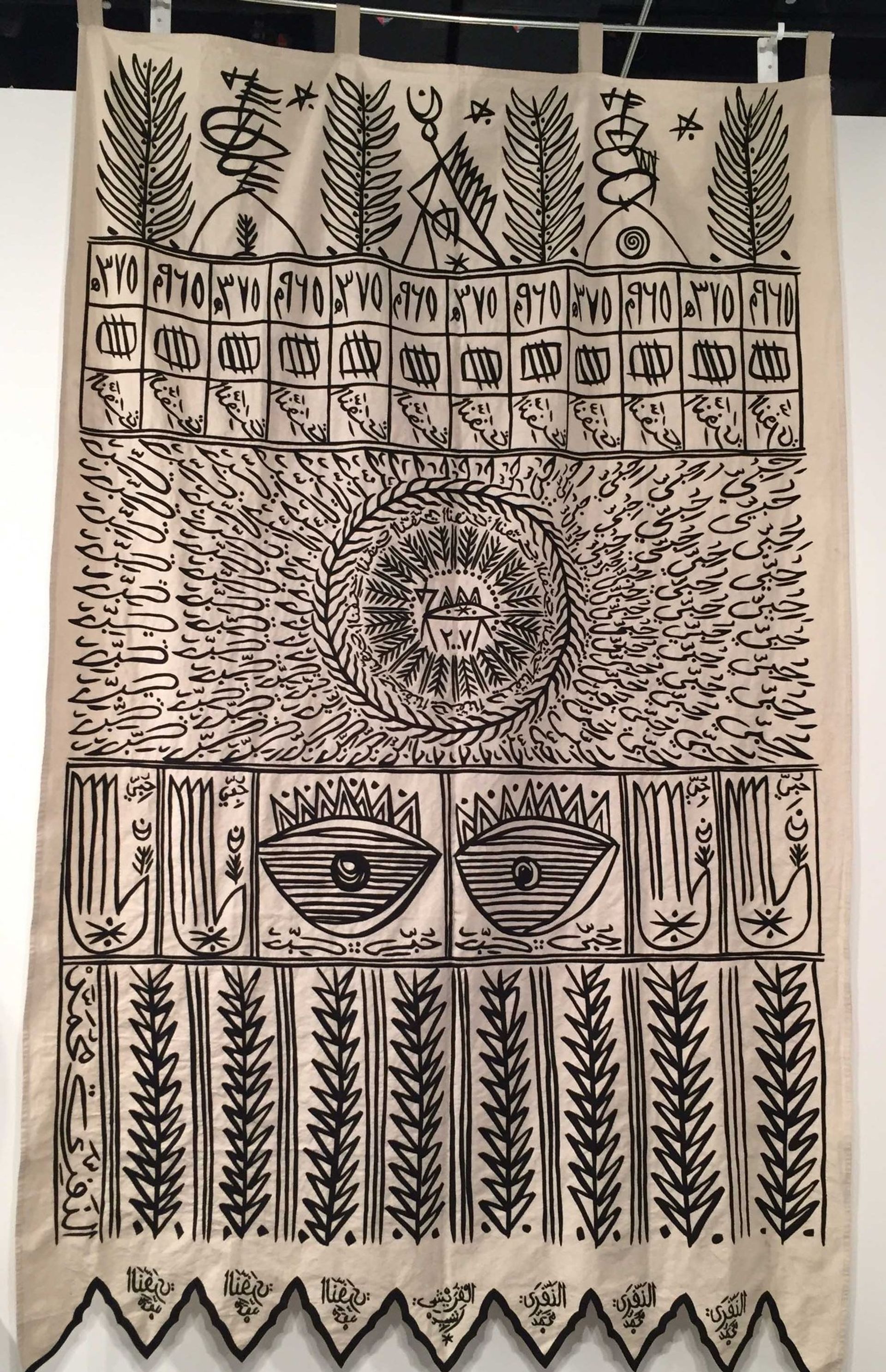

At London’s October Gallery, we talked about mysticism because they had a large calligraphic banner from the series of 99 dedicated to texts by the 14 Sufi masters.

This series won the Jameel Prize for its author, the Algerian Sufi artist Rachid Koraïchi, whose strand of gentle Islam is at the opposite end from Isil-style fundamentalism. He is known in the UAE for having decorated a carriage on the Dubai elevated railway, so the banner and his ceramics were attracting a lot of attention.

Another, even greater local hero was for sale on Sean Kelly’s stand; Idris Khan’s layered panes of glass with superimposed lettering or numbers, priced at £75,000, could have sold many times over because he is the creator of the spectacular war memorial next to the Sheikh Zayed Mosque, inaugurated on 30 November.

Dubai’s Cuadro Gallery had two stands and its owner, the curator Bashar al Shroogi, took me through a proper little retrospective he had mounted of the very sensitive, home-spun, Emirati land artist Mohammed Ahmed Ibrahim, who rarely comes down from his remote mountains of Khor Fakkan where he makes art in sympathy with the surrounding landscape, such as the coral stones bound together with lava by wire made of local copper. Very Arte Povera, you might say, except that he evolved his own art without ever having heard of the movement.

Don’t mention the wars

From Turin, another repeat exhibitor, Giorgio Persano, nearly always has some actual Arte Povera artists and Minimalist art, and for two years, the Lebanese artist, Zena El Khalil, who also has a big following as a blogger. Her 140 small wooden boxes are burned with Arabic words that are a mantra against the brutality of war: Land-Honour; Compassion-Forgiveness; Honour-Land; Compassion-Love; Love-Forgiveness. This work, which was one of the very few at the fair to be even tangentially about the ghastliness beyond the frontiers, sold to a member of the ruling house. It is as though the mere mention of the wars might shake the local peace.

Leila Heller of New York and Dubai gave a splendid dinner during the fair in her Dubai gallery, where she was displaying that grand old classic, Frank Stella’s wall sculptures from the 80s at $1m each, but in Abu Dhabi Art her works were mostly under the $100,000 mark: richly textured and colourful pieces by the Egyptian Ghada Amer, the Iranian Marcos Grigorian, and the Lebanese Nabil Nahas, to mention only some artists from the region.

Have a banana

The Italian Galleria Continua (of San Gimignano, a small Tuscan hill town, and Beijing—the most opposite addresses you can imagine) was behind the unmissable performance work: tons of bananas covering the floor, flanked by formal garden vases. Eat a banana, toss the skin in a vase and reflect on death and decay were the artist Gu Dexin’s instructions. Alexandra Munroe, the senior advisor on global arts to the Guggenheim Museum in New York , was its curator.

The two big changes in the Abu Dhabi art scene since 2009

Munroe commented on how much had evolved here since her last visit only two years ago. One of the biggest changes since Abu Dhabi Art started in 2009 is that artists from the region are no longer a specialist field, handled mainly by galleries from the region, but are internationalised and part of the Euro-American scene as well, acquired by museums such as the New York Guggenheim.

The Egyptian artist, Wael Shawky, currently the subject of big exhibition at the Castello di Rivoli in Turin, was for sale with London’s Lisson Gallery, and the Pakistani artist Imran Qureshi, who did one of his bloody flower paintings on the floor of the roof garden of the Metropolitan Museum in 2013, was on Thaddaeus Ropac’s stand.

Brigitte Schenk of Cologne was showing the famous early video work by Saudi artist Abdulnasser Gharem, Al Siraat, and she told me that he was preparing for his exhibition in 2017 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

The other big change is that local support for Abu Dhabi Art has grown year on year, helped by the fact that its venue, the Manarat al Saadiyat, is one of the few places other than malls or mosques in which to hang out. It’s actually fun. Emiratis, both sheikhs, sheikhas and commoners, and ex-pats flock with their children to see the art, do a painting class, eat street food from the stalls, and listen to music that is edgy but not rebarbative.

The most committed go to the talks by art world celebs: this year they included the international curator Okwui Enwezor; David Adjaye, architect of the new National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC; the Arte Povera artist Giuseppe Penone, who is making a 16-metre tree sculpture for inside the Louvre Abu Dhabi, and Julia Peyton Jones, former director of London’s Serpentine Gallery and the impulse behind the 16 temporary pavilions by great architects that have gone up there, year by year, since 2000.

The guest impresarios of artistic happenings were, as in previous years, the irrepressible Fabrice Bousteau, editor of Beaux Arts Magazine; and the Egyptian curator, Tarek Abou El Fetouh, who organised events reaching out from the fair to the city’s water front.

A change of director for Abu Dhabi Art

Abu Dhabi Art would not have happened without Rita Aoun. It was she who conceived of it as not just an art fair, but a complex cultural happening, and it has been she who has cajoled the international art stars and thinkers to come to Abu Dhabi and take part.

She is executive director for culture of the Abu Dhabi Tourism & Cultural Authority, and 2017 will be a busy year because the Louvre Abu Dhabi will be opening, so she has now passed responsibility for Abu Dhabi Art to Dyala Nusseibeh, who began her career with the Saatchi Gallery in London, and in 2013 launched the Istanbul art fair. As Michael Findlay said, “Emiratis are not blasé. There is no cynicism here; they thank us for bringing the art to them”. Nusseibeh can build on this well disposed public, the growing and ever more educated creative energy, not to mention the excitement the Louvre Abu Dhabi’s inauguration next year will arouse.