Five years after the Clyfford Still Museum opened its doors, much of its collection has yet to be examined. More than 300 paintings by the pioneering Abstract Expressionist whose works fill the museum remain unstretched. “A lot of the paintings still smell like they are drying—we’re the first people to unroll them since he made them,” says Dean Sobel, the museum’s director. “Sometimes it feels as though we are only about five minutes ahead of our audience.”

During Still’s lifetime, the audience for his work was limited by his antipathy to the art world and his strict prohibition against loans of his art. Since the museum opened in November 2011, its curators have worked to find inventive ways to engage the wider world while honouring Still’s strict views about how his work should be seen.

Last month, nine of Still’s most important paintings travelled to the Royal Academy of Arts in London for the first major exhibition of Abstract Expressionism in Europe in more than 50 years (until 2 January). Still is considered one of the first artists to create purely abstract compositions, but his contributions remain less well known than those of his peers.

Sobel says that Still’s will is “somewhat ambiguous” about posthumous loans, but he decided to take advantage of the opportunity after consulting the museum’s trustees, the city of Denver (which technically owns the collection) and the artist’s children. Future loans will be considered on an individual basis, he says, but no more have been planned.

In his will, Still left nearly 95% of his output to a US city that would agree to create a permanent home for his work and his work alone, “with the explicit requirement that none… be sold, given or exchanged”.

While the paintings are in London, the museum will dedicate its entire building to the first exhibition of Still’s works on paper (14 October-15 January). In April, the Los Angeles-based painter Mark Bradford will organise an exhibition of Still’s work that explores his use of the colour black. Sobel says: “Still’s paintings are only the start of what we can do.”

Curators pick their favourite finds from the Still archive

Clyfford Still in the “piano room” that served as one of many art storage places in his home in New Windsor, Maryland, 1973

The museum’s archival photographs depict hundreds of rolled paintings, works on paper and ephemera filling the Stills’ Victorian brick residence. This modest house—in which the Stills prepared meals on a hotplate and used lawn chairs as furniture, everywhere surrounded by art—was more repository than home. The photographs illustrate a remarkable effort by the artist and his family to document and preserve Still’s immense body of work, which survived decades of domestic storage in remarkable condition.

Jessie de la Cruz, archivist and digital collections manager

Diary notes on Still’s work of the early 1930s

This passage from Still’s diary sheds light on one of his lesser-known creative periods. “The paintings had nothing to do with poverty,” he writes. “I had no special pity for these men—they could face anything. The paintings came out of my feeling of the magnificence, of the tragedy of life. They were all vertical. All, man’s defiance of gravity. I wanted them to be intense.” Typical of Still’s words is an Emersonian sense of self-reliance. He stresses not the quotidian misery of the figures he painted but their elemental qualities, including the grandeur and tragedy of existence.

David Anfam, senior consulting curator

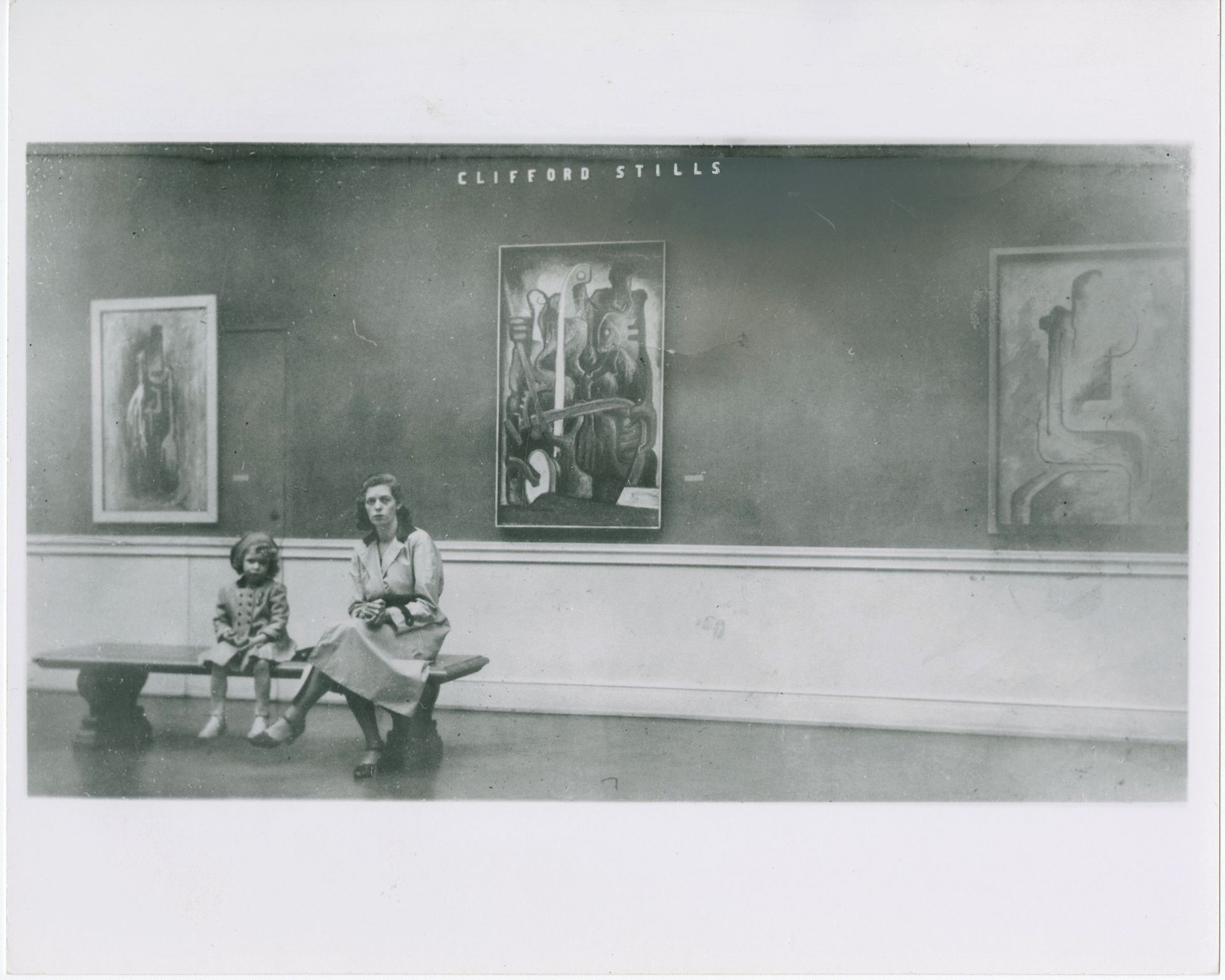

Installation view of the 1943 exhibition Paintings by Clyfford Still at the San Francisco Museum of Art, California

This installation view of Still’s 1943 solo show is one example of the archive’s voluminous documentation of Still’s exhibitions. While the works shown here (from 1936-37) represent his highly original figurative style, other works in the exhibition (from the early 1940s) were the artist’s earliest expressionistic abstractions, validating that Still was one of the most advanced artists working in the US. Images like this provide a glimpse of what visitors (including Still’s first wife, Lillian, and daughter, Diane, pictured above) experienced as art history developed before their eyes. Note the misspelling of his name on the wall (“Clifford Stills”)—a rough introduction for an artist just entering the art world.

Dean Sobel, director