Christopher Rothko, Mark Rothko's son, says that his late father would have been “upset” by the astronomical market value of his works today and unsettled by the tumultuous state of the world. Christopher Rothko was speaking at the launch of a vast show of works opening at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris this week (Mark Rothko, 18 October-2 April 2024).

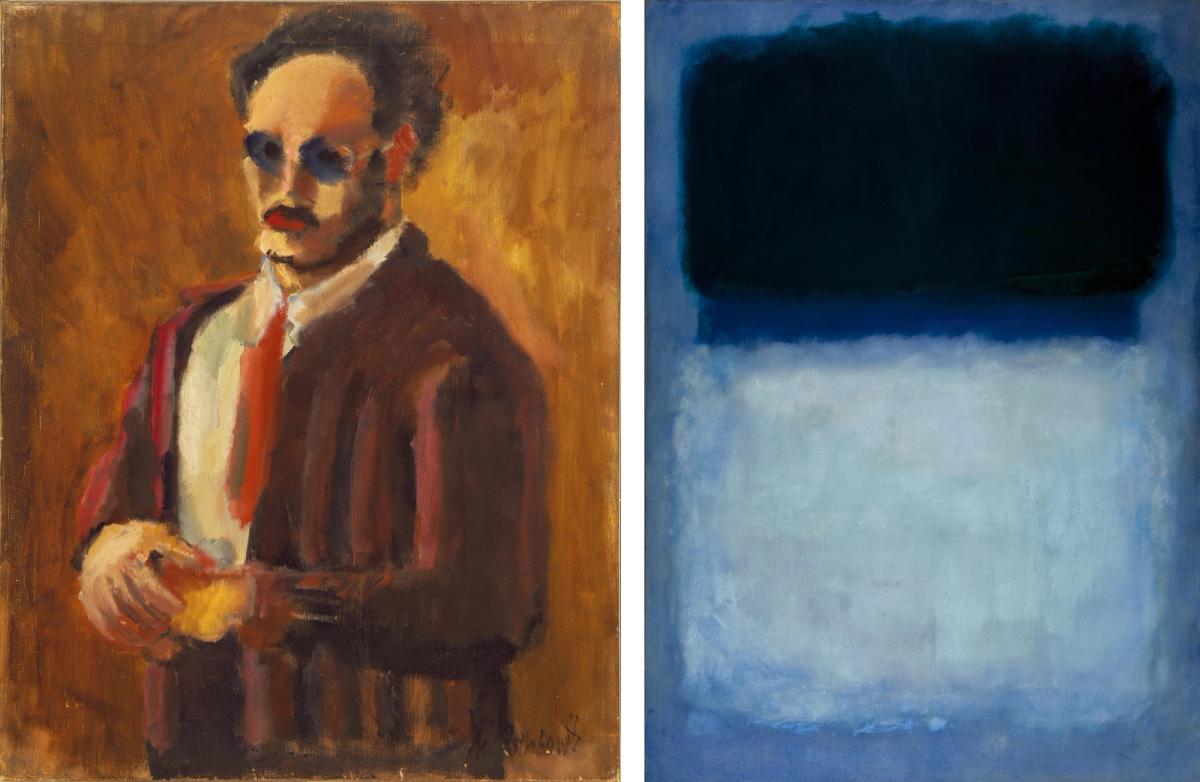

The Paris show is co-curated by the younger Rothko and includes more than 115 works drawn from collections such as the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas, and the Fondation Beyeler in Basel. The exhibition is “displayed chronologically across all of the Fondation’s spaces", tracing "the artist’s entire career from his earliest figurative paintings to the abstract works that he is most known for today”, a gallery statement says.

The market value of Mark Rothko is in the spotlight after Artnet News reported that Pace gallery is offering Olive over Red (1956) at the Paris+ par Art Basel fair this week for $40m. “The primary way that it’s [the prices for Mark Rothko's works] important to me is that it makes organising exhibitions very difficult; the cost of insurance and transport is astronomical. I’m grateful to do this show, which is really on an enormous scale; not many institutions can afford to do this,” Christopher Rothko says.

Mark Rothko's No. 10 (1957)

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko; ADAGP, Paris, 2023

So, how would Mark Rothko have responded to his stratospheric market prices today? “He would be very upset because it’s a major distraction; they become a commodity and trophy, they become something other than the experiential relationship [for the viewer sparked by his works],” Christopher Rothko says.

Today’s difficult global political climate would also have left an impression on him, the younger Rothko says. “He certainly was born into a socialist family on the brink of the Russian revolution. They left in 1913…he lived through the Great Depression in New York. He was very concerned with his fellow common man. I cannot imagine he would be pleased with what he would see today.”

Asked how many works he had loaned to the show, Christopher Rothko says: “I’m always talking about my sister [Kate Rothko Prizel] and I; we always co-ordinate. Technically, we’re two private collections but do everything together. We’ve loaned nearly 30 works. I wanted to bring paintings that Europeans would not have seen for the most part before and refresh [the selection].”

Mark Rothko's Red on Maroon (1959) from the Tate's Rothko Room

Photo: Tate; © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko/DACS 2015; ADAGP, Paris, 2023

Crucially, Tate in London has loaned nine Seagram Murals by Mark Rothko—the gallery’s entire Rothko Room—to the exhibition. “It is powerful in the UK but certainly not lacking anything [by being] here,” Christopher Rothko says. Another important ensemble of three of the four paintings that make up The Rothko Room is on loan from The Phillips Collection in Washington, DC.

Rothko died by suicide in 1970. The press statement says: “Even in the case of the 1969-1970 Black and Grey series, a simplistic interpretation of the work, associating grey and black with depression and suicide, is best avoided.” Christopher Rothko says that “this has been a reality of my life for 55 years. I try to cut out this direct connection of dark colours means depression and light colours don’t… there was no question he was very depressed at the end of his life but at that moment, he launches into a new style which was subtly different but a major step; he painted more paintings in those last two years than any other time in his life. It is never an easy formula… it’s always complicated.”

Suzanne Pagé, the artistic director of the Louis Vuitton Foundation, tells The Art Newspaper: “Rothko is completely apart [from other artists] and absolutely necessary for each of us today. He speaks about our fundamental emotions. It is paradoxical in a way: achieving profundity through abstract art.” Pagé adds in a statement: “At the heart of the exhibition are abstract works from the so-called ‘Classic’ period, from the late 1940s onwards, in which a unique colourist asserts himself in the radiant, mysterious brilliance of colour raised to incandescence.”

Mark Rothko's Untitled (The Subway) (1937)

© 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko; ADAGP, Paris, 2023; © Glenn Castellano, New-York Historical Society

The artist’s only self-portrait, dating from 1936 and drawn from the collection of Christopher Rothko, opens the show. It is subsequently followed by paintings made in the 1930s depicting urban landscapes such as the New York subway. Later works from the 1940s reflect Rothko’s progression towards abstraction via his Multiform works.

“In his classic format, he is creating infinite possibilities. Each painting starts as a new experiment with a new set of feelings and ideas; at first...it might seem like there’s nothing there. He is completely suffused in the painting; he is bringing his beliefs at that moment to the painting. If you engage with the painting, you are essentially completing that process because the meaning for you is personal; you bring your own feelings and it's an interaction,” Christopher Rothko says.

Rothko was especially reluctant to speak of his technique. “He did not want you thinking about him or the specifics of how he made the painting. If you’re preoccupied with those details, you’re taking yourself two steps away from the full impact of that interaction,” says Christopher Rothko. Dispensing with frames is also part of the experiential viewing process. “The paintings through their borders have their own frames and the rectangles are moving as if they want to cross those borders; you don’t want to box them in,” he adds.

“Suzanne reminded me that it had been nearly 25 years since the last Rothko show in Paris [at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1999]. France has only two works in public collections [at the Centre Pompidou],” Christopher Rothko says, adding that he is collaborating on a major paintings-on-paper show due to open at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC next month (19 November-31 March 2024). The show is scheduled to travel to the National Museum in Oslo next summer.