The late American artist H.C. Westermann (1922-1981) liked to walk on his hands all the time, and friends remember that change would often come spilling out of his pockets. The former acrobat also enjoyed surprising people in “serious” spaces (like museum galleries where his work was on display) by coming up to them with his feet in the air—sometimes with a cigar in his mouth for added effect. This is how he first met Frank Gehry, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) in the late 1960s. “Even when he started talking, he didn’t put his feet on the ground,” the architect recalls in the new 3D documentary Westermann: Memorial to the Idea of Man If He Was an Idea, “so I instantly fell in love with him”.

Westermann (“Cliff” to his friends) often had this kind of effect on people. His unusual yet endearing mannerisms, coupled with his unwavering devotion to craftsmanship, won the hearts of a plethora of major art-world players. Many of them appear in his new documentary—Ed Ruscha, William T. Wiley (1937-2021) and Billy Al Bengston (1934-2022) among them. A true “artist’s artist”, Westermann remains beloved more than 40 years after his death. KAWS served as executive producer on the documentary, and director Leslie Buchbinder, enamoured of both Westermann’s unique life story and the meticulous detail of his sculptures, decided it would be best to film the entire movie (her second film) in 3D. “This was my first 3D movie and will be my only 3D movie,” she tells The Art Newspaper.

Buchbinder, formerly a professional dancer, worked on Westermann for a total of nine years. She was initially inspired by Wim Wenders’s 2011 3D documentary, Pina, about the dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch. “The 3D brings dancing to life,” Buchbinder says, equating Wenders’s dancers to “moving sculpture”. In her own film, she sought to “have sculpture dance as much as possible”. The result is a lot of close-up footage of slowly rotating Westermann works popping out of the screen. “You can see the sculptures with an intimacy you can’t see even standing in front of the piece,” she says. Westermann’s acrobatic background added to the appeal of the 3D format, Buchbinder adds, as did the artist’s unique worldview. “Perspective is a huge part of the film”, she says, “both literally and metaphorically.”

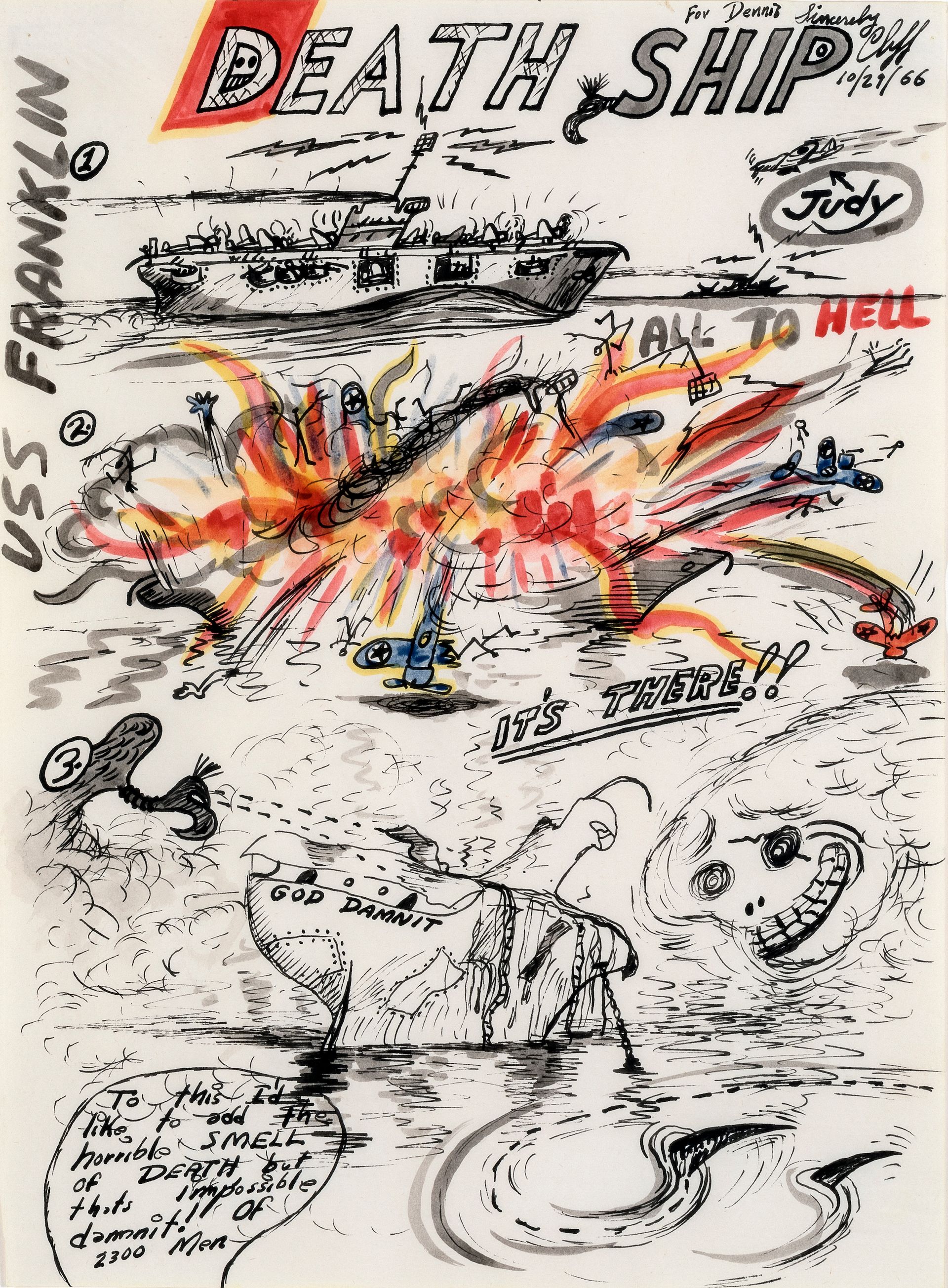

Born and raised in Los Angeles, Westermann enlisted in the US Marine Corps when he was 20, serving as an anti-aircraft gunner during the Second World War aboard the USS Enterprise, which fought in the Battle of Midway. Westermann would later make a series of “death ships” relating to the trauma he experienced during this time, specifically when the USS Franklin was downed by a kamikaze pilot, killing 2,300 people.

Still from Westermann: Memorial to the Idea of Man If He Was an Idea (2023). One of the artist's "death ship" drawings

After the war, he spent some time touring East Asia as an acrobat with the USO (United Service Organizations, which provide entertainment for members of the military and their families). When he returned to the US, Westermann enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), but he left his studies and reenlisted when the Korean War broke out. In Korea, he became completely disillusioned with the military, watching fellow soldiers die in a losing war that only dragged on. (Years later, Westermann would be extremely distraught when his son volunteered to fight in Vietnam.) He returned to SAIC to complete his studies and started woodworking for money.

In 1957, Westermann sold his first sculpture—to the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The following year, he had his first solo exhibition in Chicago. And in 1959, Westermann showed several works in the groundbreaking New Images of Man exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. In 1959, he married the artist Joanna Beall (1935-1997); the couple moved to Connecticut, where they built their own house and two art studios. In 1968, Westermann had his first major museum retrospective at Lacma, where he first walked up to Gehry on his hands; the architect was designing a Bengston exhibition. Westermann had a major retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1978, leading to other shows around the globe. In 1981, he died suddenly of a heart attack at age 58.

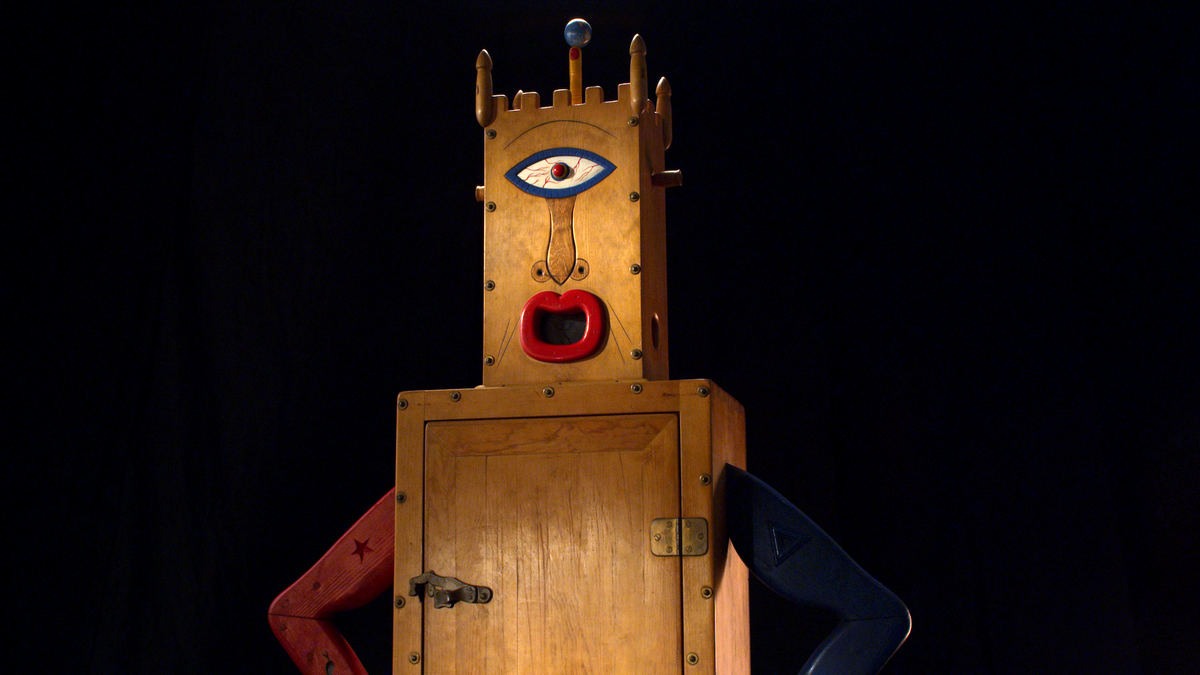

Buchbinder’s film takes its name from Westermann’s 1958 sculpture Memorial to the Idea of Man If He Was an Idea. The work is a pine box with arms akimbo and a castle-like head (with a single eye) filled with bottle caps, an acrobat and baseball player on the top level with a sinking ship underneath. “It’s the Cyclops from The Odyssey,” Buchbinder says. “It’s myopia as one of the greatest dangers, especially when it comes to war and obeying orders.”

Although Westermann’s works often appear playful, there is a darkness behind them—just like the man himself, who playfully walked on his hands while living with depression and survivor’s guilt. Buchbinder sees Westermann as a “cockeyed optimist, looking at things in a different way than other men of his era”.

The men (and women) of his era who appear in Buchbinder’s film were thrilled to participate in the documentary, the director says, largely because Westermann “meant so much to them—it wasn’t a hard ask”. And although they appear in a rather straightforward, talking-head interview style—much of Westermann, apart from the 3D filming, is fairly traditional for a documentary, including reading aloud the artist’s letters to his friends and family—Buchbinder specifically had them place objects of significance on the tables in front of them, so that gifts Westermann had given them and various other odds and ends pop to the fore.

“I encouraged show and tell during the interviews,” Buchbinder says, pointing out a couple of objects on the coffee table in front of Martha Westermann Renner, the artist’s sister: a wooden sculpture of Westermann as an acrobat made by his uncle (“artistry in the family on display”) and a commemorative Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band plate—Westermann’s head peeks out right behind George Harrison (Peter Blake, who helped design the Beatles album cover, was a fan of the artist). Meanwhile, in Gehry’s studio, the maquettes behind him are what pop out in 3D. And in front of Ruscha stands a beautiful wooden box that Westermann made for his friend and carved the words “Ed’s Varnish” onto; toward the end of the film, Ruscha lovingly shows it off to the camera.

While Westermann’s life and art are so fascinating that any documentary about him would be extremely watchable, the details provided by his letters and the heartfelt interviews with his family and friends (famous and otherwise), coupled with the 3D focus on his handcrafted objects, here provide a unique kind of intimacy with the subject. “One of the greatest gifts artists give each other is the gift of comradery,” Buchbinder says. Westermann, who was known for making far more gifts for friends than works for sale, likely would have agreed.

Watch this exclusive clip from Westermann: Memorial to the Idea of Man If He Was an Idea:

- Westermann: Memorial to the Idea of Man If He Was an Idea will screen at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, on 3 October (followed by a Q&A with Frank Gehry, Ed Ruscha, and Leslie Buchbinder) and at the Art Institute of Chicago on 19 October