Ten museums around the world will receive major gifts from the estate of Hans Arp, the artist credited as a pioneer of the Dada movement. The unprecedented gift will distribute 220 plaster sculptures to various institutions on three continents, providing greater access to a wide international audience.

The Arp estate—known as Stiftung Arp e.V., founded in 1977 and based in Berlin—announced the gift on 1 June. More than half of the receiving institutions will be acquiring their first-ever Arp works, including the Hepworth Wakefield in England, the National Museum in Oslo and Museum Beelden aan Zee in the Hague.

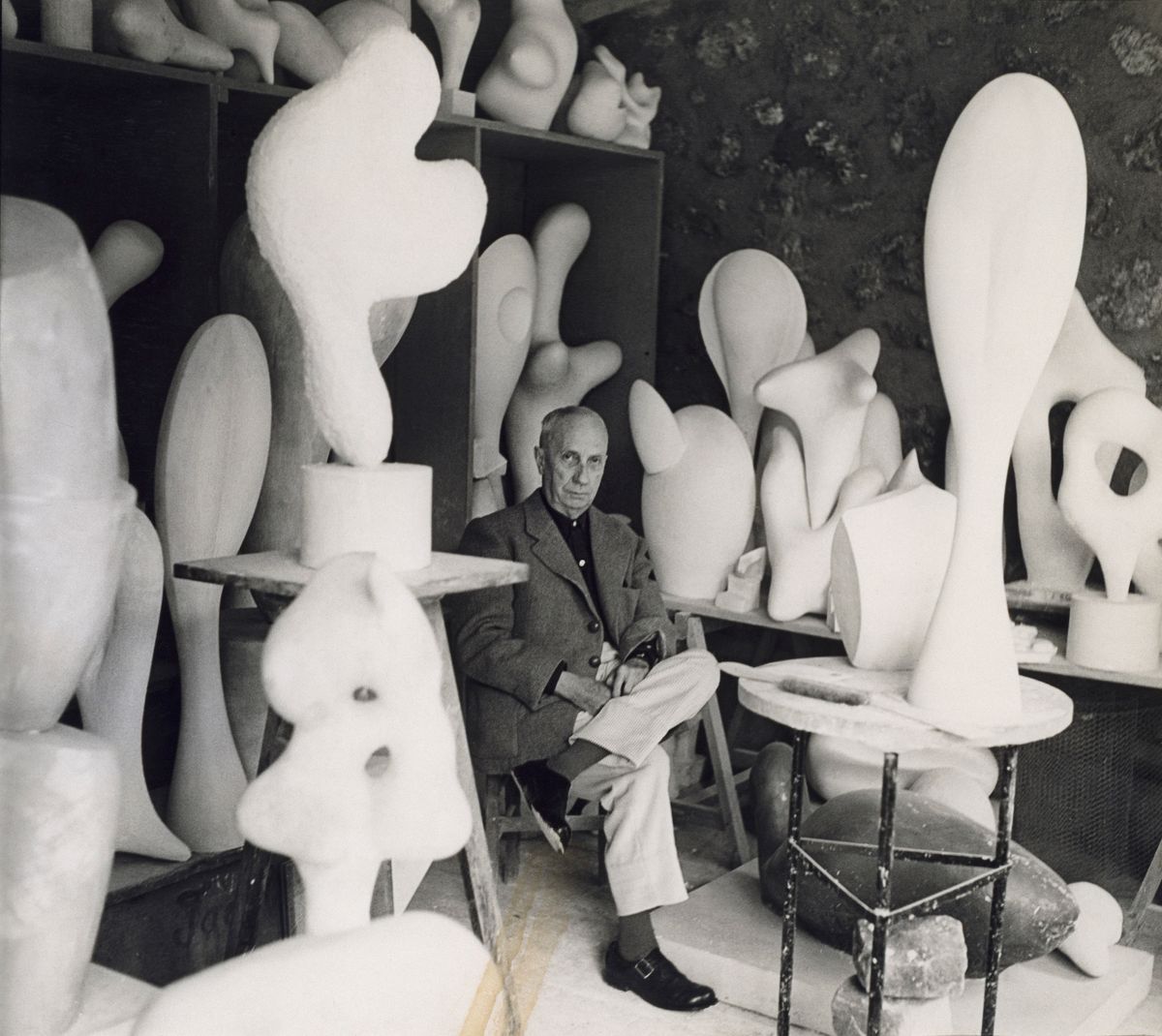

Many of the plaster works have never been publicly displayed before. Dating from between 1933 and 1966, the year Arp died at age 79, they show how the artist found endless possibility in this malleable material, transforming it into the playful biomorphic forms for which he is best known. Enabling him to experiment with sculpting techniques, these wandering, dynamically contoured pieces reflect Arp’s intuitive methods of adding and subtracting. Many were models for sculptures eventually realised in bronze or stone.

Each museum will receive 22 works and together make up a “carefully selected group” of institutions, the estate’s director Engelbert Büning said in a statement. The majority of them are in Europe: the Skissernas Museum in Lund, Sweden; Albertina in Vienna; and the Gerhard Marcks House and Arp Museum Bahnhof Rolandseck, both in Germany. Two museums, the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas and Harvard Art Museums in Massachusetts, are based in the US. And the works travelling farthest will go to Melbourne, ending up at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Hans Arp, Chosen by Flowers, around 1957-58 Photo: RüdigerLubricht, © Stiftung Arp e. V., Berlin, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2023

Parts of this geographical spread nod to the artist’s own background: born in Strasbourg, France, in 1886, to an Alsatian mother and German father, Arp lived at various turns of his life in Paris and Zürich, where in 1915 he met the artist Sophie Taeuber, his collaborator and first wife. (Stiftung Arp e.V. also oversees her artistic estate.) Arp spent his final years in Basel with the collector Marguerite Hagenbach, whom he married in 1959.

“Arp’s cultural identity was formed during a long period of charged nationalism; in reaction, the artist refused to confine himself to a single language, nationality, artistic movement, or material,” Büning said. “Shifting between abstraction and representation, organic and geometric forms—his work continues to assert the importance of art as a way to break down boundaries.”

The distribution of the estate’s holdings marks an initial step in its efforts to expand scholarship on Arp through direct gifts. The foundation plans to add more museums to this unofficial network over time, with a focus on institutions on two continents not included in the current gifts, Asia and Africa.

“By expanding research and dialogue around Arp, the donations ensure that scholars and audiences can deepen research into this important part of art history,” Büning added, “whilst recontextualizing how his output continues to resonate and hold relevance to audiences across the world today.”