Ten artists from across the Gulf have been nominated for the second Richard Mille Art Prize. The full list can be found here.

Works by the artists is on show at Louvre Abu Dhabi until 19 March and the winner will be announced 20 March.

Dana Awartani, born in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, in 1987, creates work fused traditional crafts with a contemporary context. Her BA at London’s Central Saint Martins taught her to research and develop a concept but the “thinking was more important than the end result or the making.” She went on to The Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in Shoreditch, “which was the total opposite. They told me: ‘You are not an artist, you are a craftswoman.’ It’s a way of learning. You really need to master the fundamentals in order to innovate.”

Now Awartani tries to merge these disparate traditions. “How can craft be used in contemporary art? Craft is seen as a bad word, just a decorative thing. But the history of craft is not just decorative.”

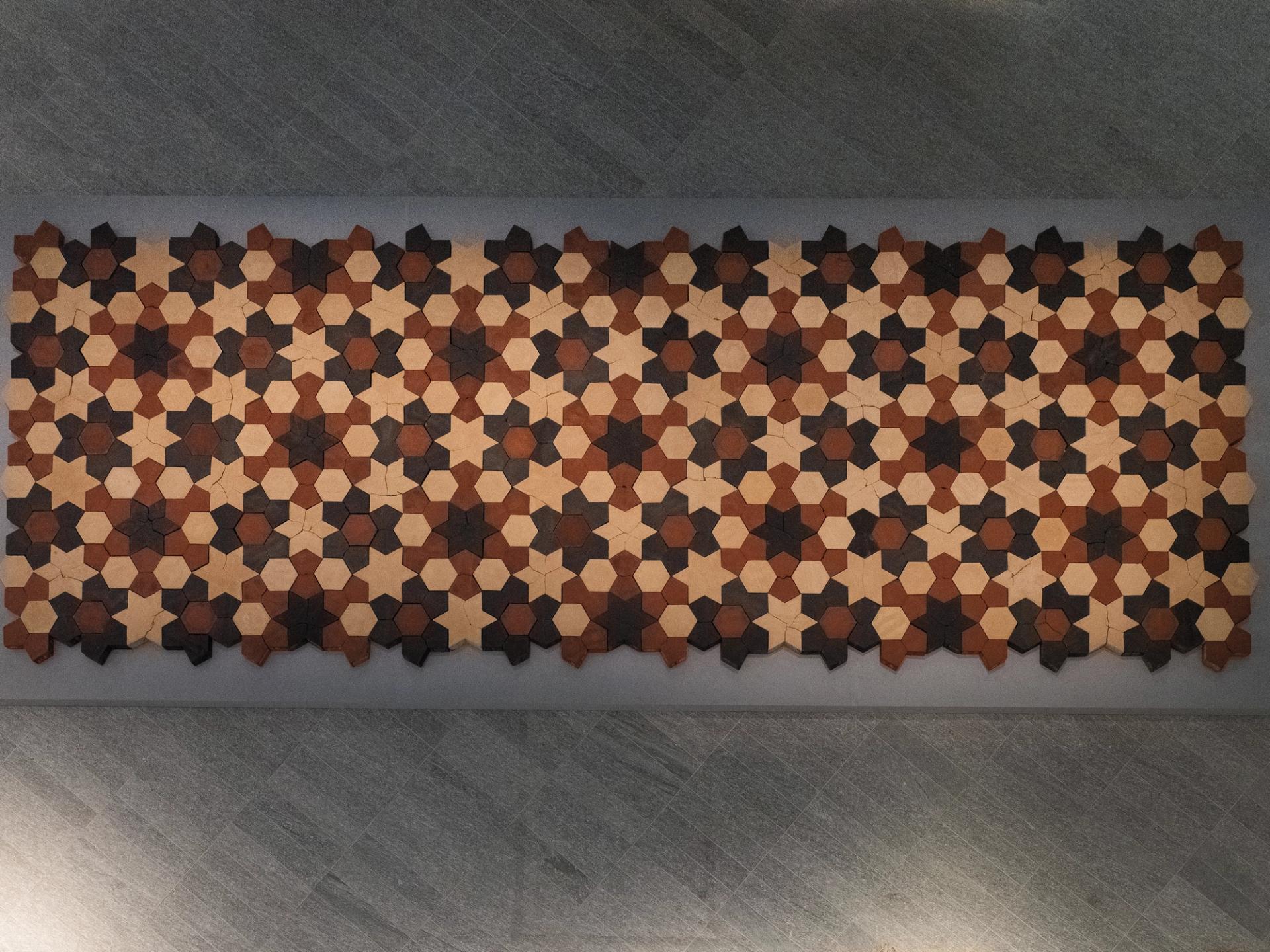

Dana Awartani's Standing by the Ruins 2022 on show at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Photo: Augustine Paredes – Seeing Things. Courtesy Department of Culture and Tourism, Abu Dhabi. Artwork © the artist

Her artwork for the Richard Mille Art Prize, Standing by the Ruins, recreates the geometric patterns found in Islamic architecture across the region. However, instead of sitting neatly, the tiles are cracked – Awartani made them by hand from mud but purposely left out the binding agent, hay, which meant they disintegrated as they dried. “It’s a work that looks at the cultural destruction that’s happened across the Middle East in recent years through violence and conflict.” Another version of the work uses a pattern from the Great Mosque of Aleppo, which has been severely damaged during the ongoing war in Syria.

Awartani was born in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Her work has been collected and shown all over the world, including at the British Museum and the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C. But in the last ten years she has seen a boom in her home city, where she still lives and works. “When I moved back from London, there was no art scene, but now that’s shifting. I’m grateful because it creates an international dialogue where you have more people coming to Saudi Arabia – a great way to understand the country or the culture is through the arts.”

Awartani is studying Islamic illumination to help preserve those skills. “Craft is something passed down. In Syria, before the war, more than 20 workshops did mother-of-pearl inlay, but since everyone was forced to flee, there’s only one left. That craft dies out with them. There’s a lot of symbolism, a lot of meaning behind the craft which has gone.”