The bustling art centre that Zarminah* manages in Afghanistan has been in survival mode since late December. The activities at the centre, which was a hotspot for women, came to an abrupt halt when the Taliban foisted a ban on women attending universities and all teaching institutes last December.

The decree was brought in as a result of women not following Islamic rules, says a Taliban official; it was enforced by the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, whose representatives barged into centres and ordered female students to leave.

“When they told the girls to leave, everyone was really upset,” Zarminah says. “One of the girls was so distressed that she fainted and we had to take her to the hospital.”

While women try to come to terms with the new reality of a life limited to the confinements of their homes, artists and art centres across the country, whose income was largely from teaching women, are trying to stay afloat with little hope in sight.

Zarminah’s centre had around 90 students, 70 of whom were women. After a brief shut down, the 24 year old was permitted to teach again but only to girls under the age of 12. Zarminah says the women have tried to continue through WhatsApp, but most either do not own a phone or cannot afford the hefty internet packages.

“I guess most of the girls will get married and have children,” she says. “They will just have to take their dreams to the grave with them.” She is uncertain how much longer they can keep the venue open as they cannot currently afford to pay their rent.

At another centre Bahar echoes Zarminah’s experience and says despite their acquiesce of the strict Taliban rules, their women’s classes were shut down. “We wore long black clothes with masks. We installed a curtain so girls would not be seen, women taught the girls. We did it all just so we could continue but they still banned us,” she says in a measured but angry tone.

“It is very sad because classes like ours were the only outlet left for women. Now there is nothing,” says Bahar as she recounts another decree that banned women from entering parks, mosques and bathhouses.

But Bahar’s students’ avidity for arts has led them to continue by meeting at each other’s homes. “Art is not easy, it takes years to master a technique. That’s why it is important to the girls to continue,” she says. “We don’t want to lose everything that we have spent years learning.”

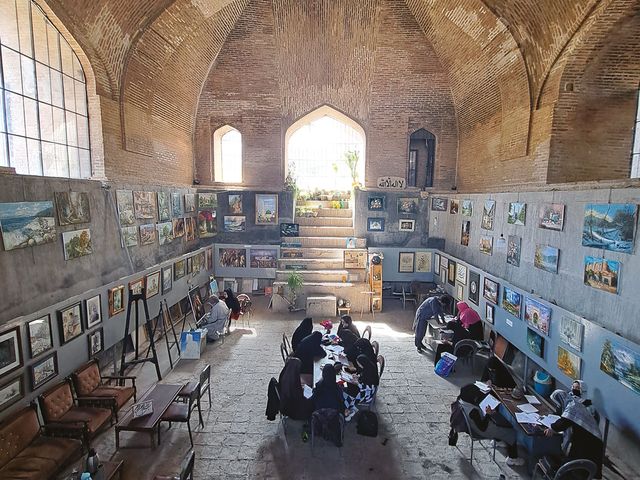

Last year The Art Newspaper reported on two Afghan artists trying to navigate their way through the uncertainties of the art scene under the new regime. Jawad Paya in Kabul and Mohammad Ebrahim Habibi in Herat both held classes for women at their galleries and outlined the financial struggles that they and their students faced due to the country’s crippling economy. The new restrictions have forced them both to re-evaluate their options.

“I haven’t been able to sleep since this happened,” Paya says. “I won’t be able to afford my art material or support my family if I can’t hold classes for women.” The 30 year old’s newly established centre had 15 female and five male students. In December he was counting on additional income from university students, who historically surged into private classes during their winter recess.

Habibi says the number of women attending his classes had increased to 50 over the last few months but now he is left with a handful of male students. “After 40 years as an artist I might have to start a new career as a driver,” he says. “The gallery can’t survive without the women.” His art centre has been an integral part of Herat’s old city since its opening in 2009.

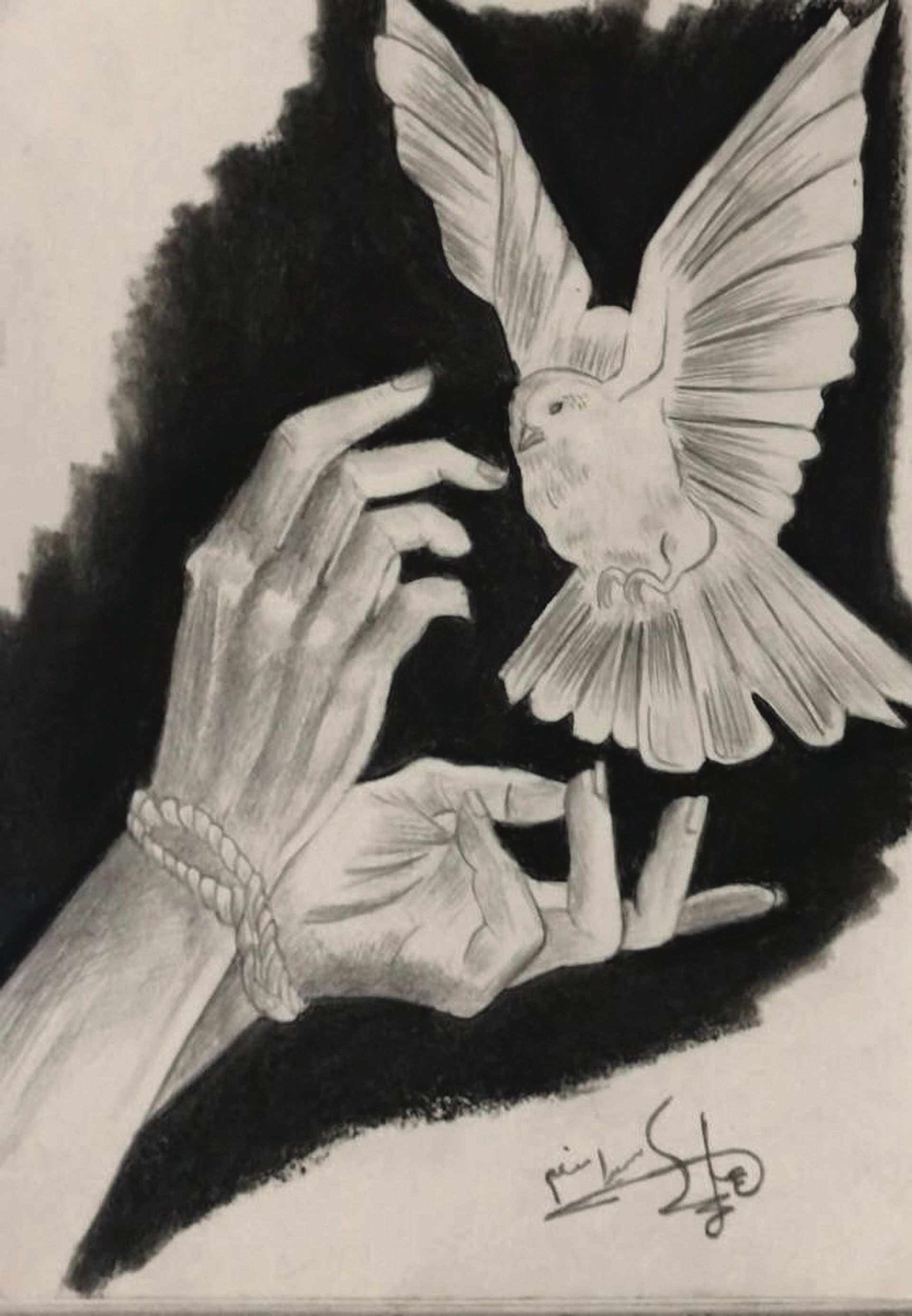

Afghan Girls Compromise by Elahe. Her art course with Mohammad Ebrahim Habibi in Herat’s old city is under threat Courtesy of the artist

Thwarted plans

One of Habibi’s students, Elahe, began taking his classes a year ago after the government art institute she was attending, which was supposed to fast track her entry into university, closed its doors to women in 2021.

“My plan was to go to university and one day start an art centre for people with hearing and speech impairments,” says the 20-year-old. University students who have been thrown out of their courses in the midst of their degrees are left equally befuddled about their future.

Sabereh’s family had not been supportive of her choice of pursuing an arts degree—they felt it was an expensive subject with an uncertain future. But Sabereh got a government job that financed her university education, which eased some of the pressures from home. According to at least one of her art lecturers, she is a “talented student”. However, when the Taliban took over the country they fired almost all female employees in government institutes and she lost her income.

The 21-year-old’s struggling family could not support her education so she searched for jobs and began sewing embroidery for 400 Afghanis ($5) a piece, each taking two months to complete. A recent job offer she had received from a private company was withdrawn in anticipation of a complete ban on women working following their banishment from non-governmental organisations.

Nooriya had been an art lecturer at a government institute for almost two decades. However, the Taliban banned women from setting foot inside the facility in 2021. She was not fired and still receives a reduced salary, but she is not permitted to teach at the facility. She believes it is a matter of time before she loses her job altogether.

“We as women are not allowed to do anything in this country,” Nooriya says. “We are just permitted to breathe, nothing else.” She lived through the first Taliban rule in the 1990s, when she was prohibited from attending university, and says she does not see a change between their rule then and now.

“I don’t see a bright future for artists or our young people in this country,” she says. “Our people are suffering, they are unemployed and hungry and so far their [the Taliban’s] only ideas for the country have been about limiting women.”

* Full names have been withheld.

Work made by women in Afghan art schools.

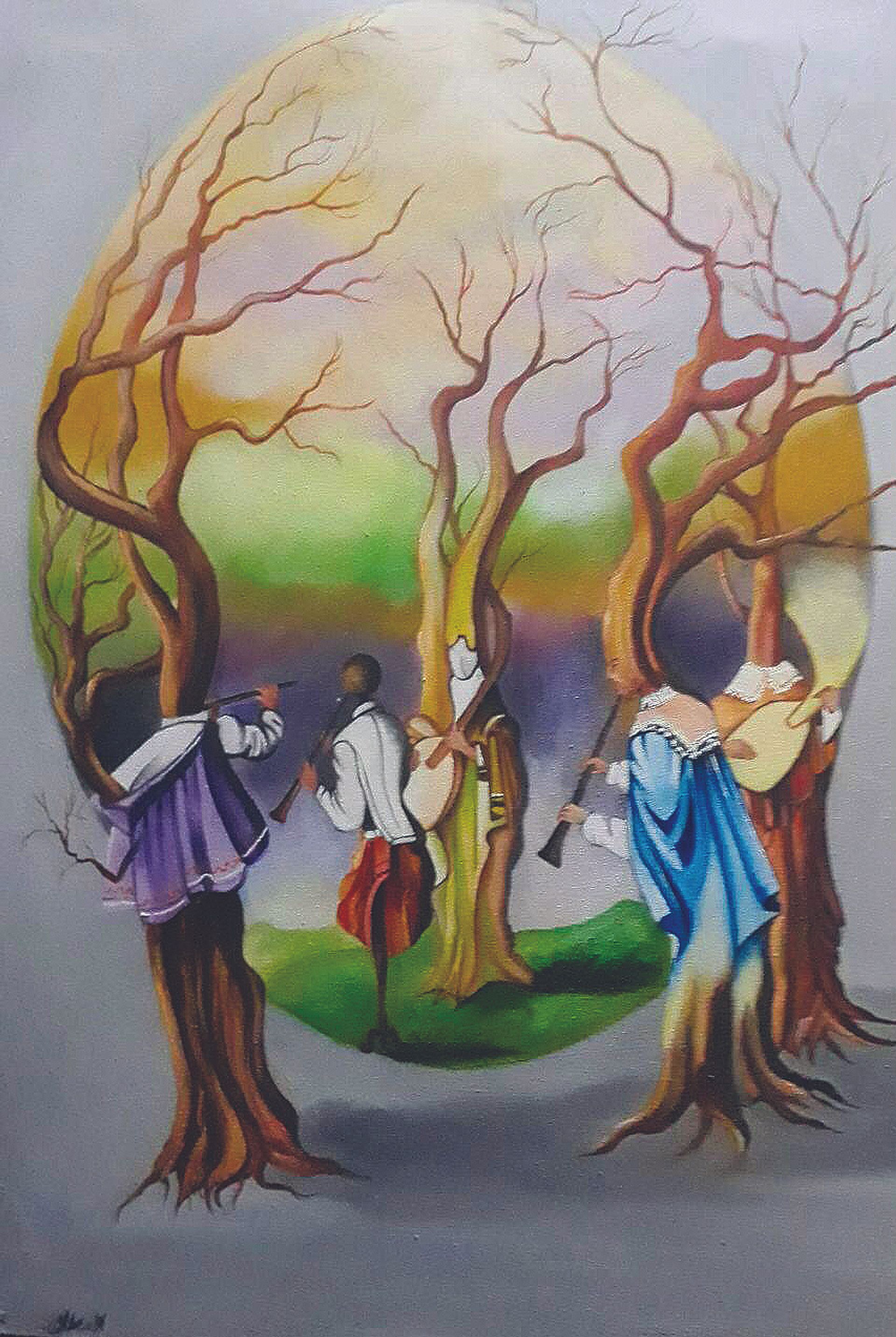

When I Couldn't Learn Music, I Played It In My Imagination

Work made by women in Afghan art schools.