MAP, or the Museum of Art & Photography, will finally officially open this month in India’s so-called Silicon Valley of Bangalore, south India, after a series of construction delays.

The museum, the first public institution to open in India for more than a decade, is the creation of the local businessman and collector Abhishek Poddar, whose donated collection has been augmented with contributions from the private collections of the Indian businessmen Deepak Puri and Rahul Sabhnani, as well as original sculptural commissions by the Indian artists Arik Levy, Ayesha Singh and Tarik Currimbhoy.

A rendering of the exterior of MAP Courtesy of MAP Museum of Art & Photography

“MAP is a people’s museum,” Poddar says in an interview. India has the largest population of young people in the world, and Poddar is eager to bring them into the museum. “You’re creating a need by starting a museum-going culture,” he says.

The museum’s director, Kamini Sawhney, will oversee the programme, both curating and exhibiting its existing collection and co-ordinating loan exhibitions. “We want the museum to attract a generation whose visual experiences are so greatly influenced by the digital world,” Sawhney says. “More than half of our population are under 25 years old; no country has more young people.”

While the pandemic held up the construction of the museum, Sawhney and Poddar focused their time on finding ways to engage with the audience that lay beyond the museum’s walls. MAP opened its virtual doors during the pandemic, with 100 exhibits available to view online—a strategy that will continue beyond the museum’s physical opening.

Anoushka Mirchandani's Wild Refuge (2021), part of the Visible/Invisible: Representations of Women in Art Through the MAP Collection exhibition Donated by Rahul Sabhnani (Private Collection). Courtesy of MAP Museum of Art and Photography

An encyclopaedia of Indian art

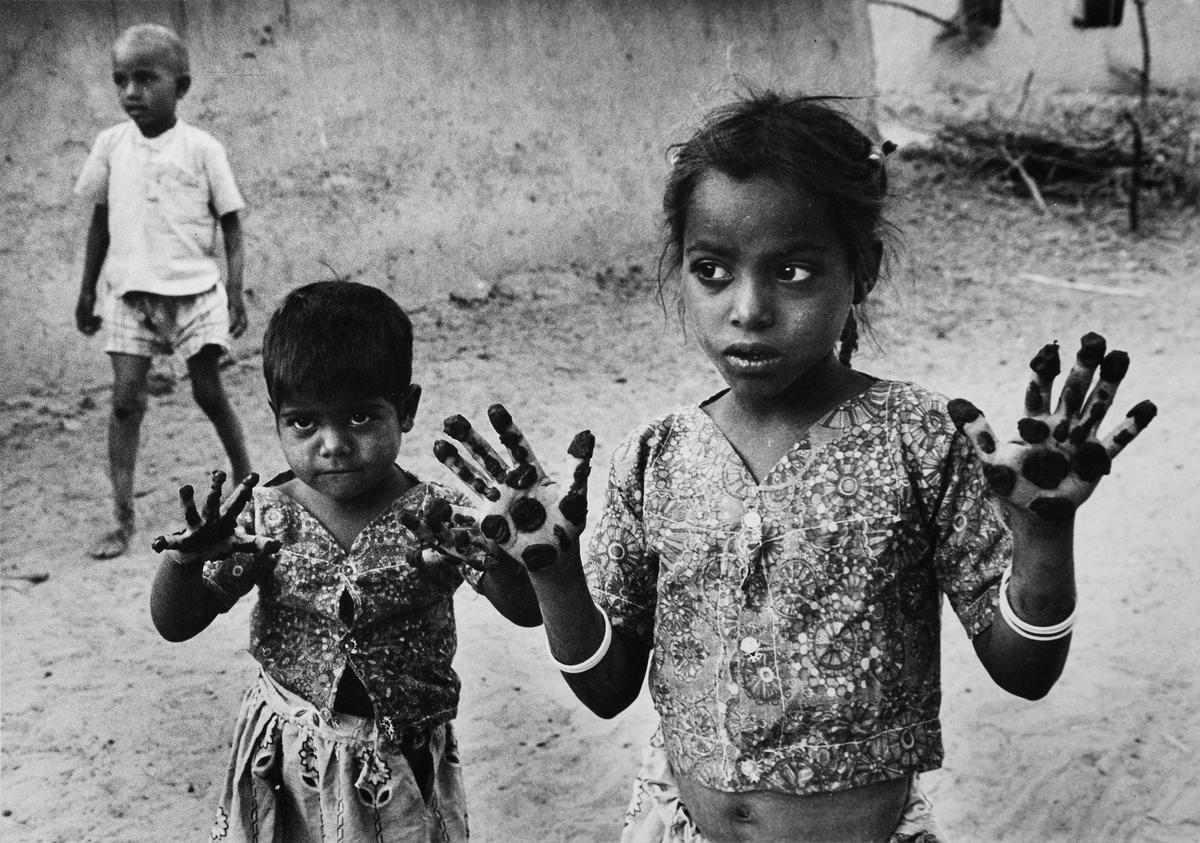

MAP will also throw its weight behind artists that have been forgotten by Western institutions. An early example is Time and Time Again, one of MAP’s inaugural exhibitions, which features a curated selection of some of the 1,000 prints of photographs by the Modernist Indian painter Jyoti Bhatt. Born in Gujarat in 1934, Bhatt, now 88, was a founding member of the Baroda Group of Artists. He is best known as a painter, with works held in the permanent collections of the British Museum in London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. But Poddar and his team have chosen instead to focus on Bhatt’s social realist photographs taken near his home in the Indian state of Gujarat in the 1950s. As well as Bhatt’s images, MAP’s collection includes photographs which tell a modern history of India, with images dating back to the mid-19th century, during which India lived under British colonial rule, through to the mass social upheavals of the 1947 Partition and on to India’s current status as a global economic superpower.

But perhaps MAP’s most significant contribution to India’s artistic heritage is its already launched Encyclopaedia of Indian Art, a vast database overseen by a team of 19 full-time writers. The database aims to tell an exhaustive history of Indian art, from 10,000-year-old cave drawings to contemporary artistic creations made over the course of the past decade. The encyclopaedia first launched in April 2022 and currently has more than 2,000 entries. The team of writers behind the project are aiming to write 20,000 entries, telling a history that has, for too long, been ignored and may, before MAP, have been forgotten entirely or never recognised.