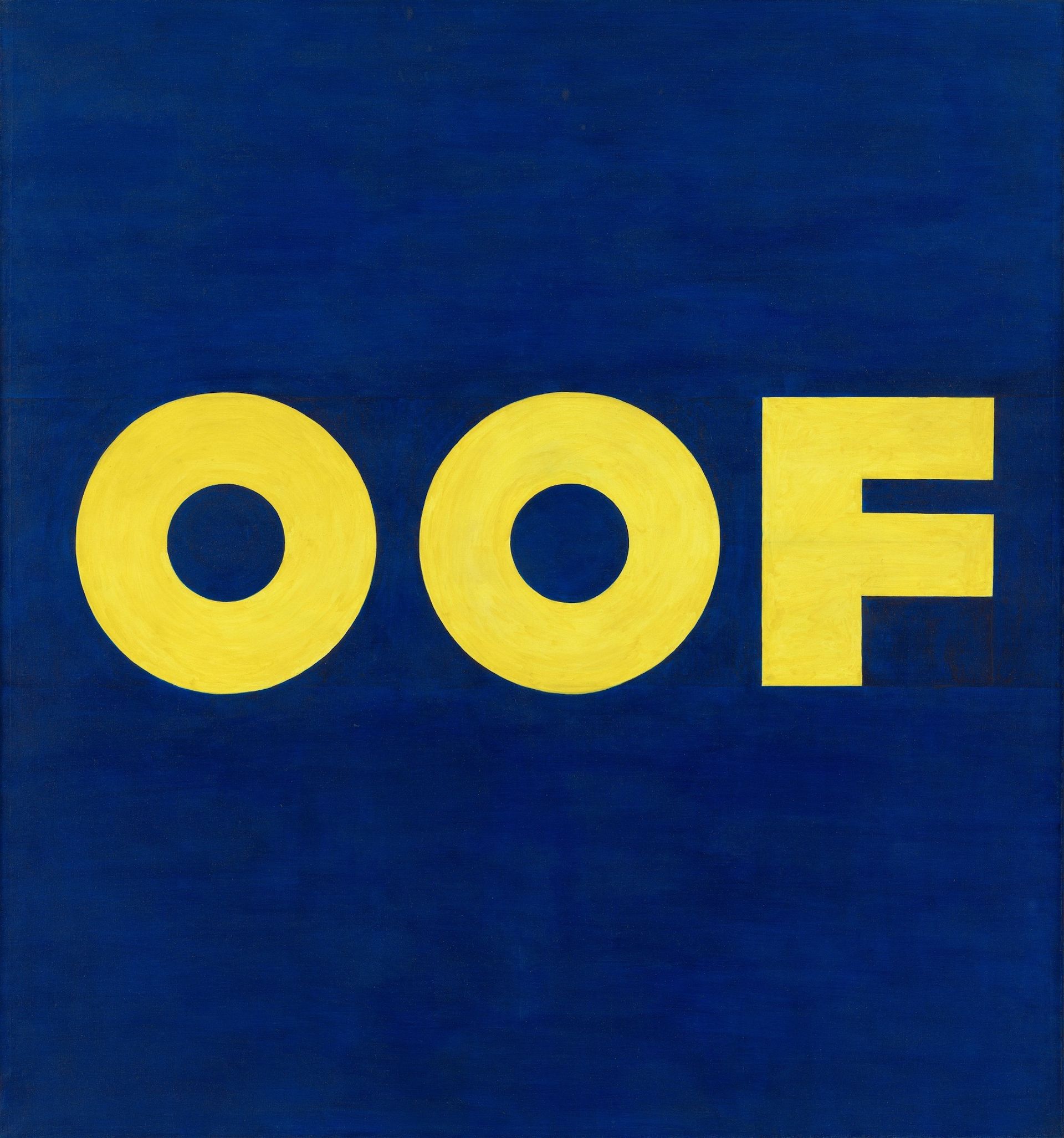

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York has built up a considerable collection of works by Ed Ruscha—including his iconic painting OOF (1962, reworked 1963)—but it has never mounted a solo exhibition of his works. That will change next September when it presents ED RUSCHA / NOW THEN, which will not only be the museum’s first show dedicated to Ruscha but also his most comprehensive retrospective to date.

Organised by MoMA’s chief curator of drawings and prints Christophe Cherix, with assistant curator Ana Torok and curatorial assistant Kiko Aebi, the exhibition will emphasise Ruscha’s cross-disciplinary approach, featuring more than 250 works produced from 1958 onward, among them paintings, drawings, prints, film, photography, books and installations. The last includes Ruscha’s only single-room installation, Chocolate Room (1970), a multisensory interior fully lined with paper screen-printed with chocolate paste. Also on view will be recent works, from his series of text paintings on drum skins, created between 2017 and 2019, to pieces currently in the making.

“Ed’s work clearly today feels as one of the most influential practices of his generation, and having the chance to work directly with the artist was what was really a trigger,” Cherix says. “But I think most importantly, at least to me, was the fact that such a show had never happened anywhere. The capacity to bring together prime examples of his work over a span of 65 years and to do that across mediums—to be able to show him as a painter, as a bookmaker, as a filmmaker, as a photographer, as a draughtsman—I think it will lead to a profound re-examination of his work.”

Ed Ruscha, News from the News, Mews, Pews, Brews, Stews & Dues series, 1970. Publisher: Editions Alecto, London. Printer: Alecto Studios, London. Edition: proof before the edition of 125. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchased through the generosity of Kathy and Richard S. Fuld, Jr. © Edward Ruscha, courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, photo Peter Butler

Expected to take over the museum’s sixth-floor galleries, the exhibition will unfold according to a loose chronology. There will be grand moments, including dedicated space for Ruscha’s wide, large-scale paintings from the early 1960s; and his Course of Empire paintings (1992/2003-05) that marry boxy Los Angeles buildings with open skies and will be shown alongside Ruscha’s extensive photographic archive of Los Angeles streets. There will also be intimate moments that invite close looking at artist-books and works on paper, such as drawings Ruscha made on the road, often hitchhiking through the US. The curators hope to track the development of an artist who explored the full force of language as an aesthetic and utilitarian tool, while avoiding the impulse to neatly define his career.

“We saw a lot of beautiful, medium-specific exhibitions of his work in the last 20 years, but he was also boxed into categories. He was a Pop artist because he was interested in popular culture. He was a conceptual artist because he used language. He was an LA artist because he was interested by public spaces around him,” Cherix says. “So what would happen if you take those labels off and try to really understand the singularity of his practice—how someone can begin with language in a word painting in the early 1960s and keep using some of those elements, while completely changing his practice.”

The exhibition will feature works that demonstrate Ruscha’s interest in unusual materials, such as gunpowder, exquisitely controlled to render words in ribbon-form. Then there’s soft chocolate, which will cover hundreds of sheets of paper for Chocolate Room. First presented at the Venice Biennale in 1970, where it was visited by crowds of humans and ants, the room will make its New York debut at MoMA, where printers will create new chocolate sheets on site. Cherix is less concerned about vermin in the galleries, and more so by how to keep the room structurally sound over the show’s four-month run.

“MoMA has the capacity to control the climate much more effectively than in the past, so we hope to avoid any pest damage,” he says. “Part of the challenge is, of course, maintaining it, and we are making a number of tests in our galleries to really understand how that chocolate surface might change over time. The artist himself is not worried about it. He totally accepts that the work might change.”

Ed Ruscha, OOF, 1962 (reworked 1963). Gift of Agnes Gund, the Louis and Bessie Adler Foundation, Inc., Robert and Meryl Meltzer, Jerry I. Speyer, Anna Marie and Robert F. Shapiro, Emily and Jerry Spiegel, an anonymous donor, and purchase. © Edward Ruscha, courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, photo Denis Doorly

Visitors may be surprised to learn that this is the museum’s first solo show dedicated to Ruscha, whose works are often on view either in its permanent collection galleries or in special exhibitions. Cherix says he shares this feeling but can’t speak to why MoMA had not previously organised a solo exhibition.

“I wouldn’t say that curators before my generation didn’t pay attention to his work because the collection they built is really remarkable, with absolutely prime examples,” he says. “So it’s not true the institution didn’t pay attention to the work. But it’s true that the institution never committed to an examination of his practice.”

MoMA has been collecting Ruscha’s work since 1968, beginning with OOF—a simple composition that embodies his incisive use of words laced with humour. It began pursuing the idea of a retrospective in 2018, with some delay in planning caused by the museum’s $450m expansion and the pandemic. The exhibition will open on September 10 2023, and run through 6 January 2024, after which it will travel to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma), which has co-organised the show, in April 2024.