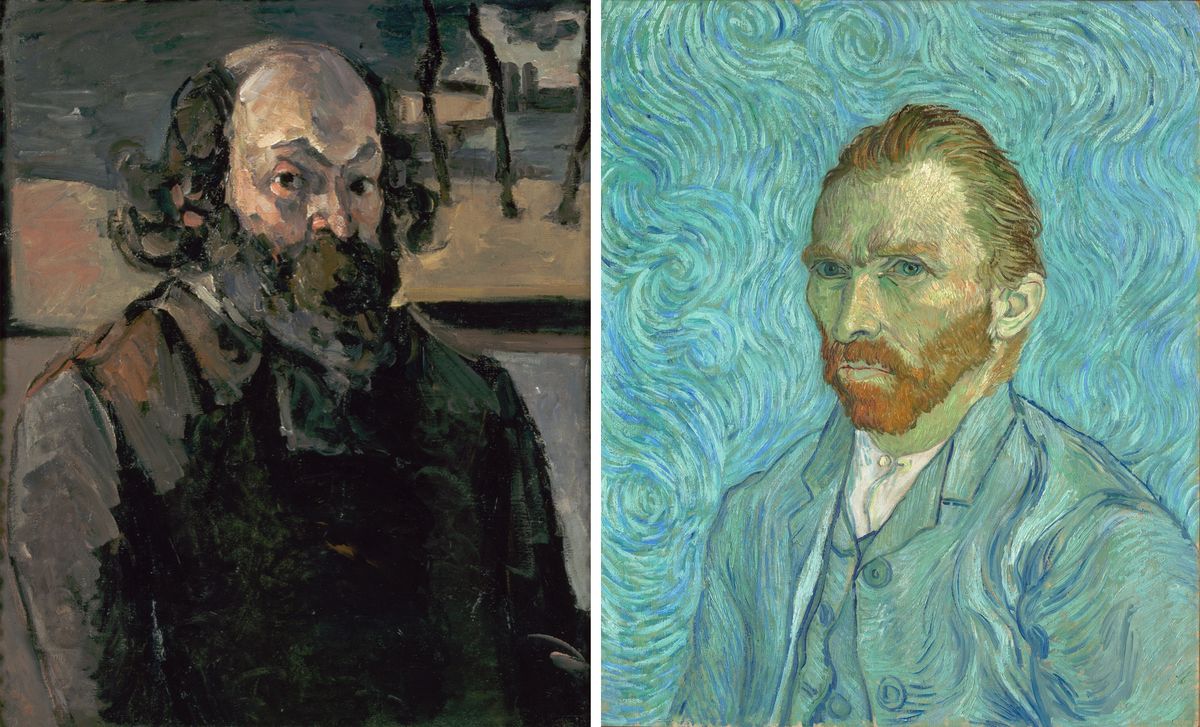

Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne both lived in Paris, Provence and Auvers-sur-Oise—but did they actually meet? Although evidence of an encounter remains tantalisingly sketchy, they undoubtedly knew each other’s work. Along with Paul Gauguin, they were the leading Post-Impressionists, the artists who paved the way for 20th-century art.

As Tate Modern’s Cezanne exhibition opens in London (5 October-12 March 2023), after its earlier successful presentation in Chicago, it is an opportune moment to delve into links between these two pioneering artists.

Natalia Sidlina, the Tate curator responsible for the London show, stresses the connections between the two artists. Along with the common places where they worked, they had “similar circles of friends, dealers and patrons”.

But Sidlina also points to key differences: “When it came to finding inspiration, their approaches couldn’t have been more different. Van Gogh found his idyll in a withdrawal to the exotic southern land and light of Provence. For Cézanne, the same place signified the return to his roots, deep and meaningful engagement with the local and the familiar.”

If the two artists did meet, it would have been in Paris. In February 1888 Vincent had arrived there to live with his brother Theo in Montmartre.

Emile Bernard, a mutual friend of Van Gogh and Cézanne, wrote about an apparent meeting of the two artists at the shop of Julien Tanguy, a paint seller who promoted the work of the artistic avant-garde.

Van Gogh showed Cézanne some of his pictures, which were stored there. Bernard reported that after inspecting them, Cézanne bluntly responded: “Truly, you paint like a madman!”

The two artists were indeed regular visitors to Tanguy’s shop, but the story may be apocryphal, since Cézanne spent only a little time in Paris during Van Gogh’s two-year stay. Possibly Cézanne first encountered the paintings of the Dutchman at Tanguy’s slightly later.

In February 1888 Van Gogh headed for Provence. He was well aware that Cézanne heralded from Aix-en-Provence. So the Frenchman's presence there might have strengthened Van Gogh’s resolve to move to Arles, 70km away, although this remains speculation. In the end, Van Gogh never actually visited Aix.

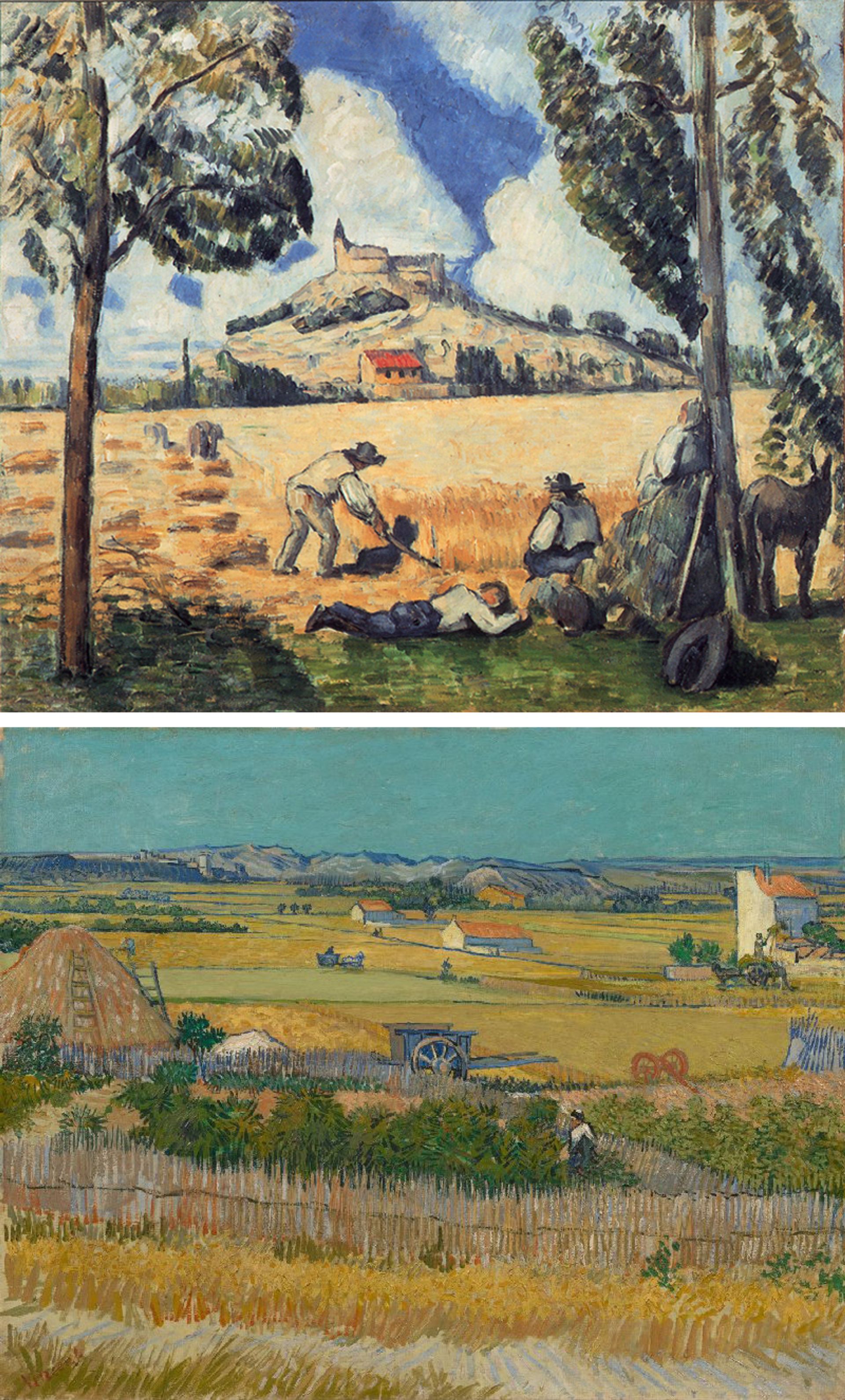

Cézanne’s The Harvest (around 1877) and Van Gogh’s The Harvest (June 1888) Credit: private collection, Japan and Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Van Gogh particularly admired Cézanne’s The Harvest (around 1877), an early work that he had seen in Paris. In June 1888, four months after his arrival in Arles, he recalled the painting, writing that it “presented the harsh side of Provence so forcefully”. He added that “the countryside near Aix—where Cézanne works—it’s precisely the same as here”.

In the same letter Van Gogh recounted that he was then “working on a landscape with wheatfields”, which is also entitled The Harvest (June 1888). So Cézanne was very much on his mind while he was painting this summer masterpiece.

Although the subject is similar, the two artists tackled it in their own personal ways. Van Gogh captured a bird’s-eye view with the horizon close to the top of the canvas, as was his style. Cézanne’s composition was more conventional, built up with his parallel brushstrokes.

In May 1888 Vincent wrote about Cézanne’s orchard blossom paintings, linking them to the works that he was doing of the same springtime subject: “The few landscapes by Cézanne that I know render it very, very well, and I regret not having seen more of them.”

Van Gogh’s most famous Provençal canvas is of course his Sunflowers (August 1888). Throughout his career Cézanne, too, loved painting flower still lifes, often in similar rustic pots. But once again, although tackling the same subject, their results were strikingly different.

Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (August 1888) and Cézanne’s Vase of Tulips (around 1890) Credit: National Gallery, London and Art Institute of Chicago (Mr. and Mrs. Lewis Larned Coburn Memorial Collection)

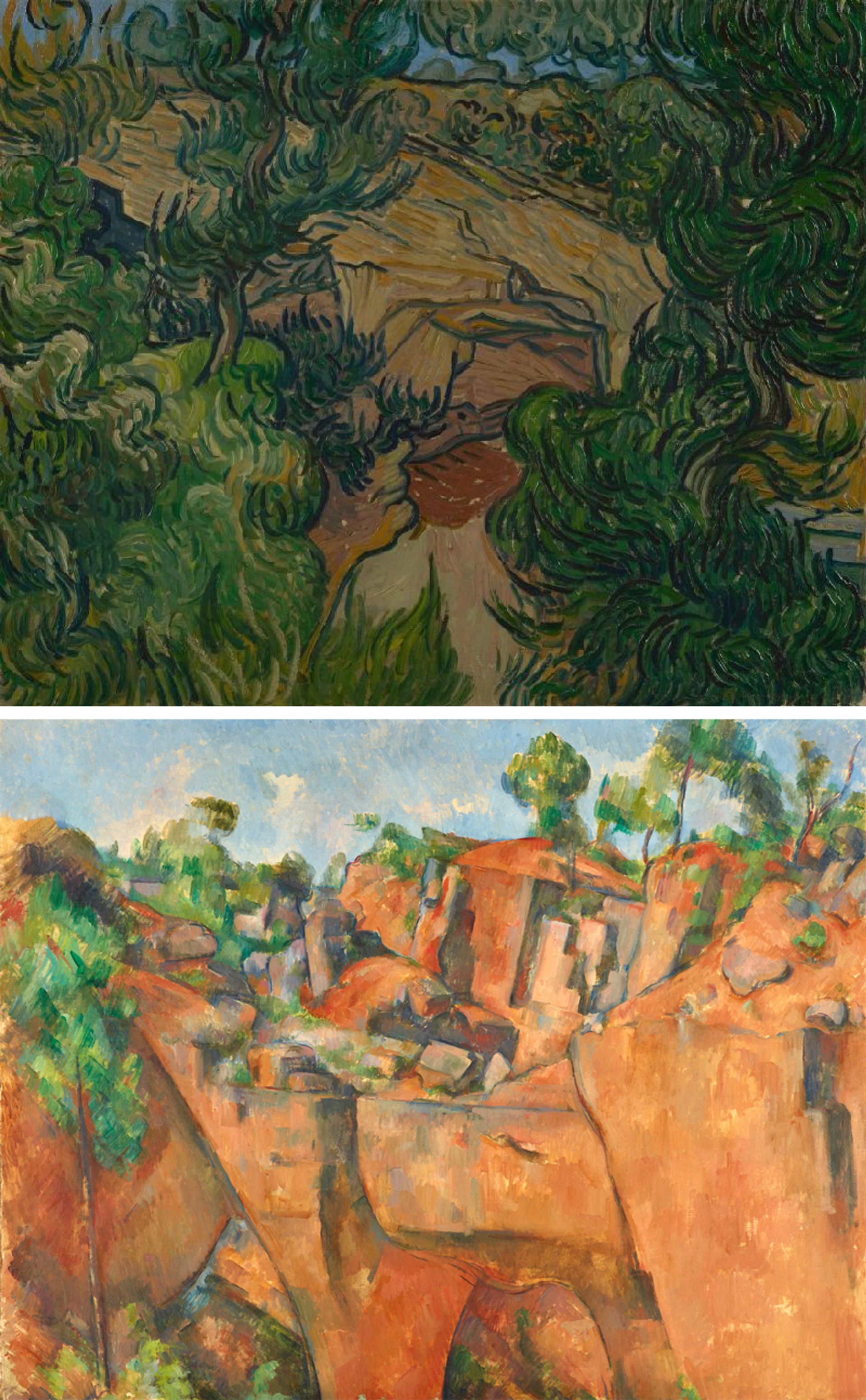

In May 1890, following the mutilation of his ear, Van Gogh moved to the asylum on the outskirts of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. This lay adjacent to an ancient quarry, where he painted on at least two occasions.

Six years later Cézanne made his own series of pictures of the quarry of Bibémus, just to the east of Aix. It is unlikely that Cézanne knew of Van Gogh’s two quarry scenes, but it is revealing to see how they both tackled similar subject matter. Rather than realistic depictions, both artists emphasised the sculptural forms of the hand-hewn rocks.

Van Gogh’s Entrance to a Quarry (October 1889) and Cézanne’s The Quarry at Bibémus (around 1895) Credits: private collection and Folkwang Museum, Essen

After leaving Provence in May 1890, Van Gogh moved to the village of Auvers-sur-Oise, just north of Paris. It was there that he killed himself ten weeks later. Cézanne had lived in Auvers many years earlier, in 1872-74. The Tate exhibition includes Cézanne’s atmospheric view of the village.

Cézanne’s Auvers, panoramic View (1873-74), on show in the Tate exhibition Credit: Art Institute of Chicago

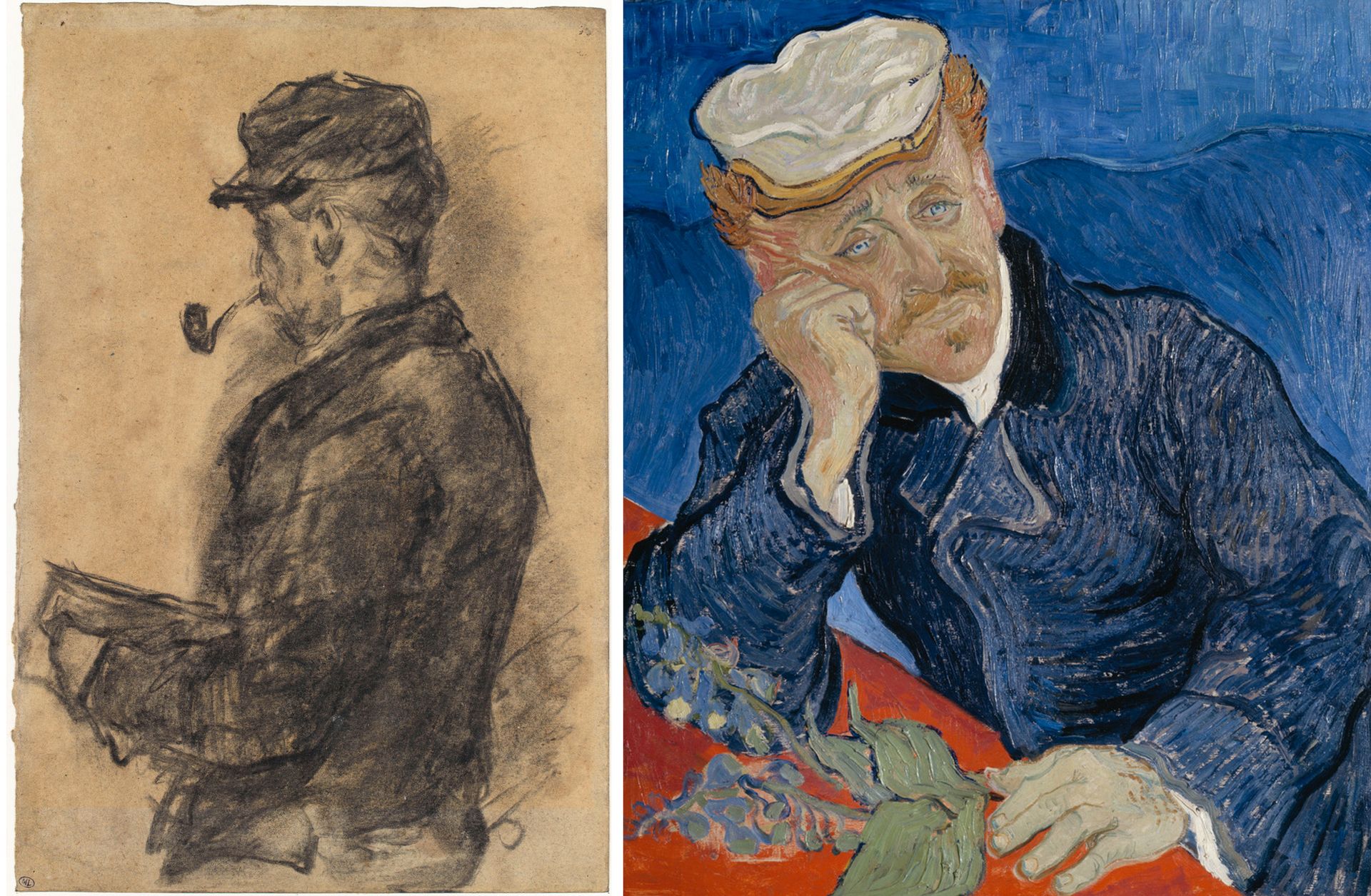

In Auvers both painters became good friends with Dr Paul Gachet, an amateur artist, supporter of avant-garde art and a serious collector.

Cézanne’s drawn Portrait of Dr Paul Gachet in his studio (1872-73) and Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Paul Gachet (June 1890) Credit: Musée d’Orsay, Paris

It was at Dr Gachet’s that Van Gogh had the opportunity to really study Cézanne’s work, as his host owned more than 20 of his paintings. In May 1890 Vincent singled out in a letter to Theo “two fine bouquets”, still lifes of flowers.

Cézanne’s The House of Dr Gachet at Auvers (around 1873)—the doctor's home is the tall white building slightly further away Credit: Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Vincent compared himself to Cézanne as a fellow painter of Provence, but also acknowledged the differences. As he wrote to Theo, they were both “painting the same countryside”, although in slightly different places. But “Cézanne’s almost diffident and conscientious brushstroke” was quite unlike his own work. Vincent added that he, like Cézanne, had to contend with the mistral: the powerful wind that blows down the valley of the Rhône and made painting outside challenging.

Van Gogh certainly admired Cézanne’s work, although it is less clear whether the reverse was true. The critic Joachim Gasquet wrote that Cézanne would speak of Van Gogh, “always with sympathy”. But Ambroise Vollard, Cézanne’s dealer, wrote that the artist “could not endure” Van Gogh. Perhaps Cézanne’s view evolved over time.

In 1904, towards the end of his life, Cézanne advised Bernard to break free artistically: “You’ll soon be able to turn your back on the Gauguins and Gogs” (this is the phonetic way that Van Gogh’s name is often pronounced by the French).

Comparing the work of Cézanne and Van Gogh is revealing, since their radical styles were so different. Cézanne’s light brushwork is rhythmic, often applied in parallel strokes. He was particularly interested in forms—whether in landscapes or still lifes. However, Van Gogh, especially during his mature period in France, worked with thick impasto paint in a more expressionist manner.

The two artists’ contrasting techniques are particularly clear when they tackle the same subject. Two portraits, both done around the same time (and, by chance, both now at the Art Institute of Chicago), are remarkably similar compositions, but so personal in style.

Cézanne’s Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Chair (1888-90)—on show in the Tate exhibition—and Van Gogh’s Madame Roulin rocking the Cradle (La Berceuse) Credit: Art Institute of Chicago

Van Gogh referred to his fellow artist as Père (Father) Cézanne, a sign of respect for a painter who was 14 years older. He particularly admired Cézanne’s dedication to his art.

Writing to his younger artist friend Bernard, Vincent made a crude comment on Cézanne: “If he has a good hard-on in his work it’s because he’s not overly dissipated through riotous living.” Put more delicately, Van Gogh believed that Cézanne’s energy went into painting, rather than more transitory pleasures.