It may be the smallest state on the planet, but the Vatican City also boasts a stunning art collection that is the envy of the world. Successive popes generated an unrivalled bounty of art, lavishing enormous amounts of money on paintings, frescoes, architecture and sculptures to project the Church's immense power and cement their own reputations in the annals of history. The sprawling Vatican Museums comprise the Sistine Chapel, private papal apartments and dozens of art collections spanning ancient sculpture, Renaissance masters, and Modern and contemporary art. With some 20,000 works (of the vast 70,000-strong collection) displayed in around 1,400 rooms, chapels and galleries, it can be easy to miss the highlights. Here are our suggestions for what to tick off your list first.

Michelangelo’s frescoes (1508–41), Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museums

Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to fresco the Sistine Ceiling in 1508. The artist spent the next four years replacing the lapis lazuli sky ceiling dotted with gold stars with personages and 13 scenes from the Old Testament, including the Fall of Man, Noah and the Great Flood and the iconic Creation of Adam. Completed 25 years after he finished the ceiling, Michelangelo's Last Judgement fresco on the altar wall—inspired by Dante’s Inferno—bursts with graphic detail, with the terrified damned dragged down to hell by devils.

Michelangelo’s Pietà (1497–99), St Peter’s Basilica

Before the Sistine Chapel commission, Michelangelo identified more as a sculptor than a painter. La Pietà, the artist's first great work, typifies his deeply expressive sculptural style. Mary holds a lifeless Christ, her face emanating excruciating, silent pain. This is not the only noteworthy work in St Peter’s Basilica, where Bernini’s statue of St Longinus (1629-38) also draws throngs. It should be said that St Peter's Basilica is a tremendous work of art in itself. With its huge dome conceived by Michelangelo (based on Brunelleschi’s for Florence’s Cathedral) and Bernini-designed niche housing relics, the church—the world’s largest—is a towering monument to Papal wealth.

Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ (around 1600–04), Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican Museums

In this stunning example of Caravaggio's dynamic and dramatic realism, straining figures heave Christ's limp body into the tomb. One places a finger inside a wound—a detail likely to make squeamish viewers grimace. There is no scenic background, only a wall of inky blackness that contrasts with starkly lit figures (an illuminated Mary Cleophas raises her eyes and arms like Saint Paul seeking spiritual guidance). While an unmistakable example of Caravaggio’s unique baroque style, the painting is also steeped in the High Renaissance, with Michelangelo's Pietà and Raphael's Deposition (1507) both clear influences.

Van Gogh’s Pietà (around 1890), Collection of Modern and Contemporary Art, Vatican Museums

Van Gogh painted this work just months before committing suicide. Some have suggested the lifeless, bearded figure of Christ is a kind of self portrait. Inspired by Delocroix’s own version of the same subject, the work takes pride of place in the 55 rooms of the Borgia apartment that house the Collection of Modern and Contemporary Art, inaugurated in 1973 after Pope Paul VI claimed the Church had become distanced from contemporary art. The Madonna thrusts her arms forwards, sorrowfully presenting the passion of Christ to the world. A larger, more brightly coloured version of the Pietà is displayed at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

Augustus of Prima Porta (first century AD), Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums

This iconic sculpture of Augustus Caesar, the first emperor of the Roman Empire, is one of the most famous works of art from the ancient world. Carved by expert Greek sculptors, the full-length original work shows Augustus addressing his troops in the classic adlocutio pose. His breastplate is richly decorated with the reliefs of a Parthian king, and a cosmic landscape featuring the goddess Diana, the chariots of Apollo, and Aurora, the goddess of Earth.

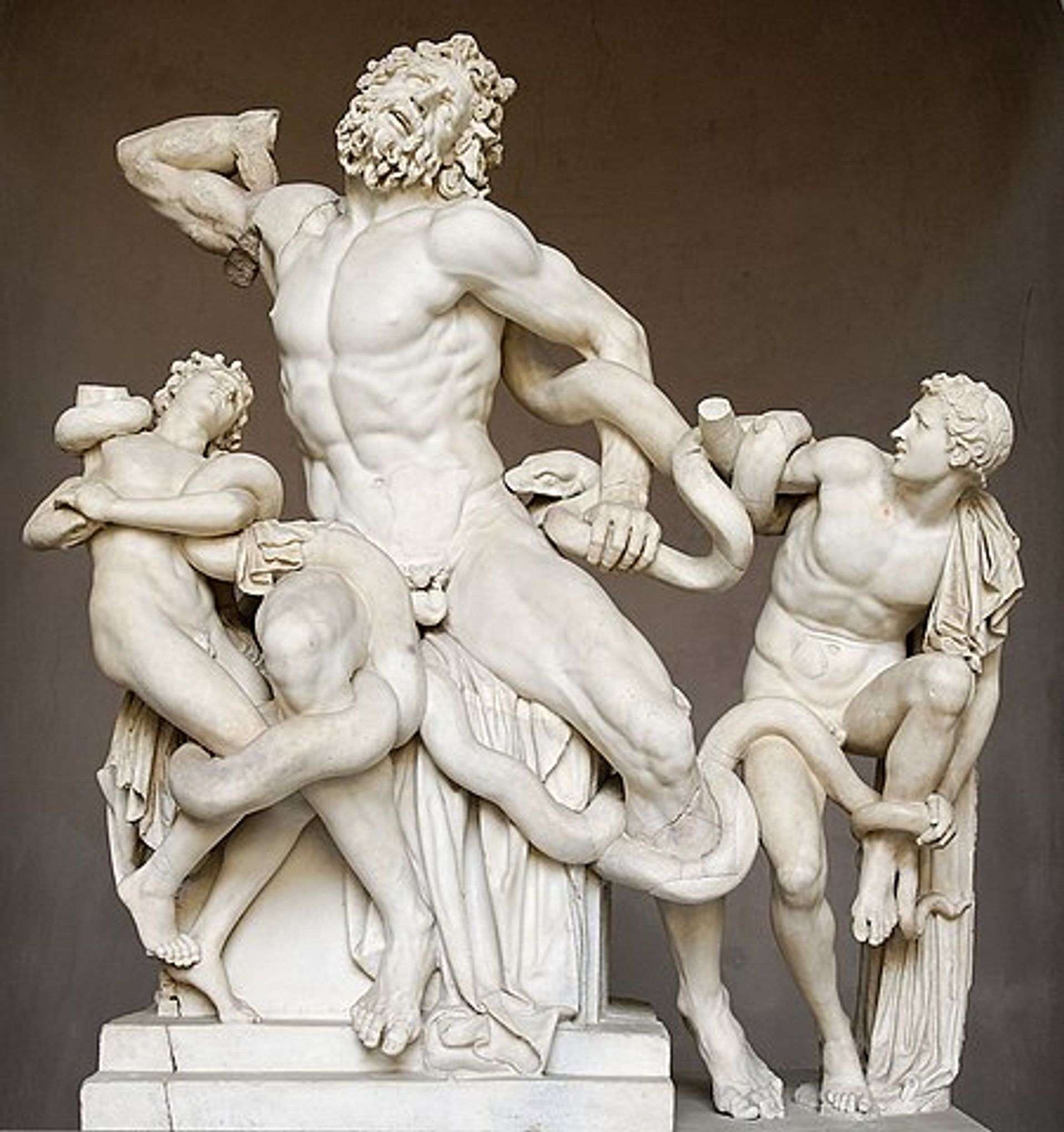

Laocoön and His Sons (around 40–30 BC), Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums

If Augustus of Prima Porta is one of the best-known works of art from the ancient world, Laocoön and His Sons is possibly the finest. Back in the first century AD, the Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder described it as "a work to be set above all that the arts of painting and sculpture have produced". The 6ft depiction of Laocoön, the Trojan priest, with his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus, was discovered in 1506 in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis in Rome. When the work was discovered, Pope Julius II sent excited court artists, including Michelangelo, to watch it being unearthed. The sculpture shows a snake wrapping itself around the characters’s legs, their faces contorted in horror. According to the British classicist Nigel Spivey, the work is “the prototypical icon of human agony in Western art”.

Raphael’s The School of Athens (1509–1511), Raphael's Rooms, Vatican Museums

Pope Alexander VI lavishly decorated his papal Borgia apartments in the late 15th century. Aiming to outdo his predecessor, Julius II commissioned Raphael to fresco four rooms in his own papal living quarters. Adorning the Stanza della Segnatura, the first of the rooms, The School of Athens celebrates the marriage of art, philosophy and science: the hallmark of the Renaissance that was blooming at the time. A who’s who of intellectuals and artists—from Perugino to Bramante to Socrates—gathers in a sweeping building that recalls the architecture of St Peter’s. Plato points to the heavens, a reference to his theory of forms, while Aristotle holds out a flattened palm, emphasising his focus on concrete matters.

Raphael’s The Transfiguration (1516–20), Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican Museums

Raphael's last work—which the art historian Giorgio Vasari called "the most famous, the most beautiful and most divine"—marks the culmination of the artist’s output. The painting combines two stories from the book of Matthew in an allegorical juxtaposition of the flaws of men and divine redemptive power. In the upper part, a transfigured Christ is shown elevated in front of billowing, illuminated clouds with the prophets Moses and Elijah on either side. In the lower part, apostles futilely try to rid a boy of demons. The work bridges artistic languages: while the characters strike Mannerist-style dramatic poses, proto-Baroque chiaroscuro lighting cranks up the dynamic tension.

The Matisse Room, Collection of Modern and Contemporary Art, Vatican Museums

In 1947, Henri Matisse started work on the Chapelle du Rosaire in Vence on the French Riviera (his first and only religious work). He desgined everything from the stained glass to the interior furnishings, murals and priests’ vestments. More than 60 years later, Pierre Matisse, the artist’s son, donated the Vence plans, models and preparatory sketches to the Vatican. Visitors to the dedicated Matisse Room at the Collection of Modern Religious Art can admire three full-size sketches for the bright stained glass window; in which green represents vegetation, yellow the sun, and blue the Mediterranean Sea. A drawing of the Virgin and Child conceived for the chapel's white ceramic panels, a bronze cast of an altar cross and five silk chasubles are also displayed.

Fra Angelico’s Frescoes (1447–51), Niccoline Chapel, Vatican Museums

Visitors passing from the Raphael Rooms to the Sala dei Chiaroscuro often miss the small doorway to the Cappella Niccolina which was once the private chapel of Nicholas V (Pope from 1447 to 1455). The chapel is lined with beautifully preserved frescoes by Fra Angelico—the devout Florentine monk and early Renaissance artist—depicting the life and martyrdom of St Stephen and St Lawrence. Fine architectural details in the backgrounds allude to Nicholas V's desire to rebuild Rome as the new capital city of Christianity.