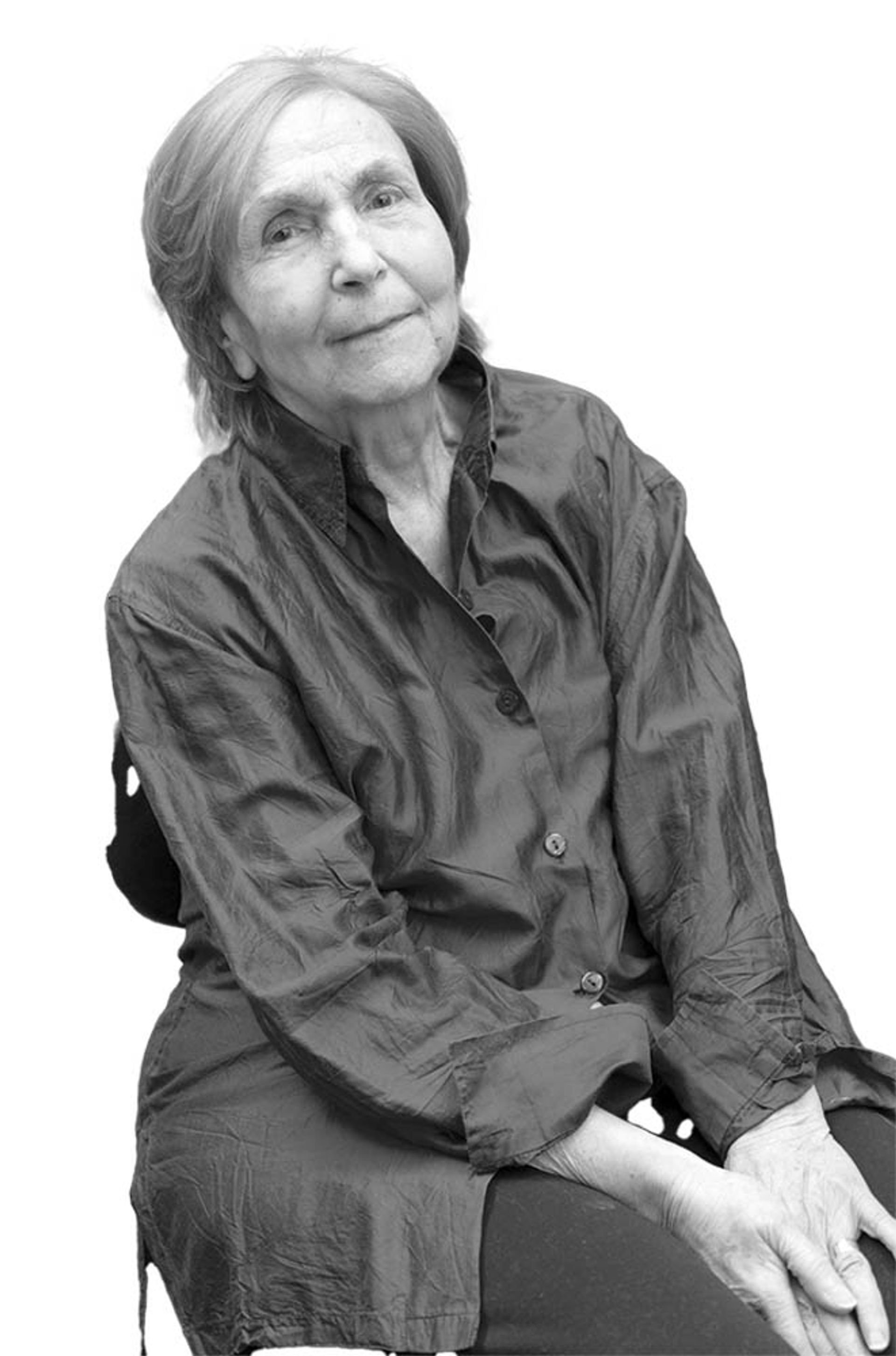

Stories always have an end but, according to Paula Rego, “What you can do in pictures, that never stops.” It’s true—the influence of the British and Portuguese artist, who died in June aged 87, will continue to live on for generations, says Sophie Lindo, an associate director of Cristea Roberts Gallery: “She’s always been on it and we’ve been behind.”

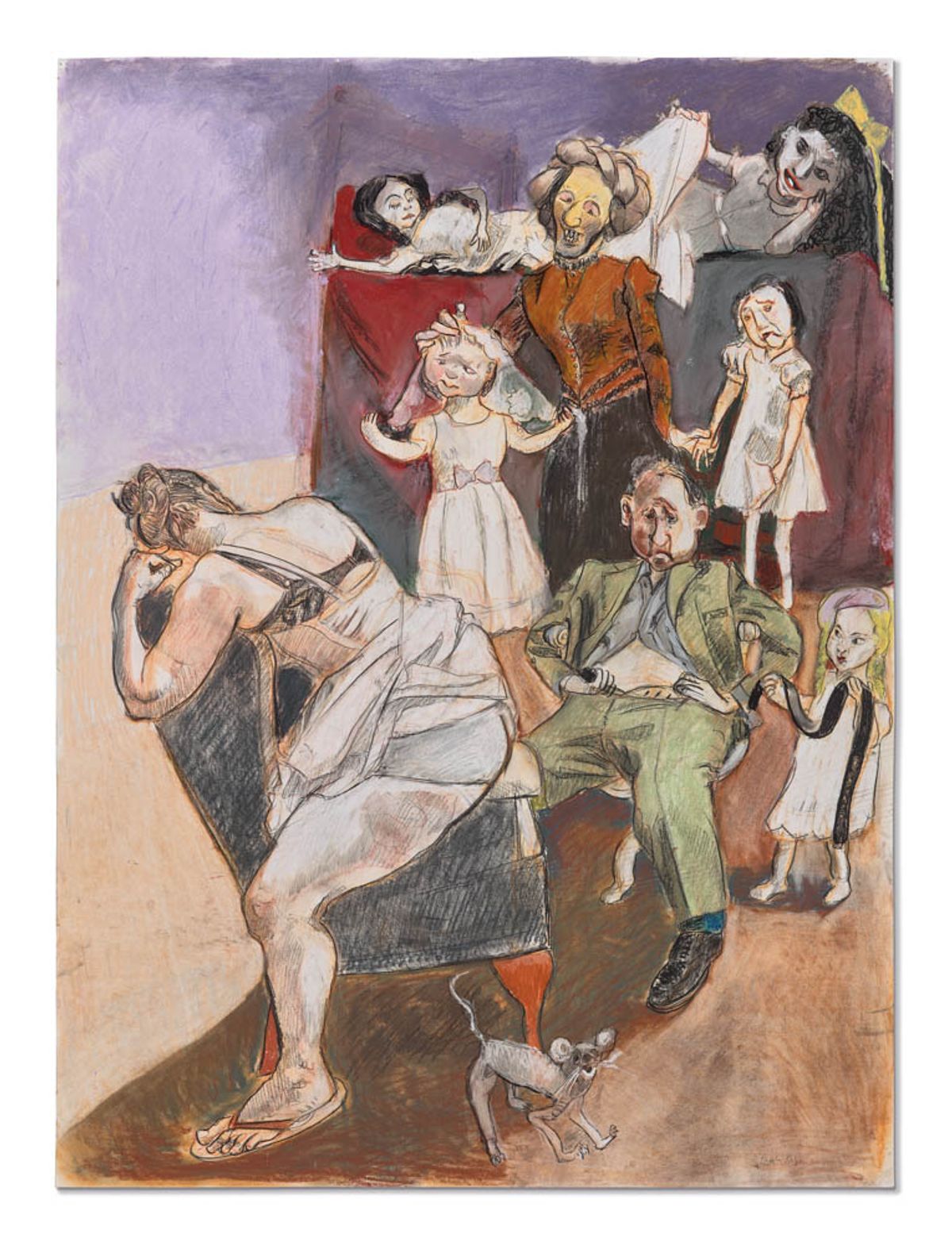

Throughout her nearly 70-year career, Rego has consistently returned to themes of oppression, violence against women and abuses of power in her paintings and drawings, often weaving together fairy tales, personal memory and political narratives to create deliciously dark images that are at once unsettling, beautiful and powerful.

Paula Rego died in June, aged 87 © Nick Willing

Indeed, Rego’s works have been powerful enough to shape legislation. In a 2019 interview, Rego said she considers her 1998-99 Abortion Series—a suite of paintings and etchings depicting the dangers of criminalising abortion made in response to a failed legalisation referendum in Portugal—among the best she has done “because they are true, and they were effective in helping to change the law in Portugal [in 2007]”. According to Lindo, there is now urgent interest among US venues to show these works following the US Supreme Court's decision to overturn Roe v Wade decision.

Rego used storytelling through art as a tool for political commentary from early on in her career, with some of her earliest pieces—notably Salazar Vomiting The Homeland (1960), which can be found in a prominent Iberian collection—addressing the violence meted out by the Fascist dictatorship in her native Portugal. After attending the Slade School of Art, in London, she showed in the 1960s with the London Group alongside peers such as David Hockney and Frank Auerbach.

The Policeman’s Daughter (1987), one of Rego’s best-known works, was first displayed at her presentation at London’s Serpentine Galleries in 1988. The show marked her return to public attention after two decades in which she had cared full-time for her ailing artist husband Victor Willing and their children until his death in the same year. (The London dealer Timothy Taylor announced representation of Willing’s estate in June.) This painting of a young woman polishing a jackboot while angrily shoving her fist up it deftly underscores her talent for rendering women as oppressed—but not repressed—subjects. In the early 1990s, Rego became an artist-in-residence at the National Gallery in London, and she showed widely across Britain especially through the early noughties, after joining Marlborough Gallery.

Paula Rego's auction record—£1.14m— is for The Cadet and His Sister (1988) © Paula Rego

Recent exhibitions have seen her reputation “catapulted” to a larger stage, according to Matt Carey-Williams, the head of sales at Victoria Miro, which has represented the artist since 2020. These include the largest retrospective of her work to date—which opened at Tate Britain in July 2021 before travelling to the Kunstmuseum in Den Haag and, presently, the Museo Picasso in Málaga—as well as an acclaimed installation in Cecilia Alemani’s The Milk of Dreams at this year’s Venice Biennale.

Prices

Crucially, auction prices for many of Rego’s works belie her renown. Her record for a painting has remained at £1.14m since 2015, when her 1988 large-scale painting, The Cadet and his Sister, sold at Sotheby’s in London. This figure stands in stark contrast to the prices paid for her monumental paintings on the private secondary market, where such works can often fetch £3m-£6m. This difference can be attributed to the fact that Rego’s paintings rarely come up at auction and many have been acquired by institutions or long-time private collectors, mostly in Portugal and the UK.

When asked about the cautious estimate of £70,000-£100,000 on an untitled painting from 1957, on the block at Christie’s day sale in London on 1 July, Anna Touzin, the firm’s head of sale, says: “Early paintings, especially, are hardly ever seen. When they are, we price them conservatively.”

Moreover, Rego is best known for her master draughtsmanship, and her detailed works on paper from the latter half of her career, especially the 1980-90s, are considered of paramount importance. As Carey-Williams puts it: “She was able to make pastel sing like oil paint.”

Indeed, the artist’s auction record for a work on paper—£1.18m—was set at Sotheby’s London in 2021 for a pastel on canvas, Good Dog (1994)—a work from the artist’s highly coveted series depicting women behaving like dogs. A pastel and charcoal drawing, Stretched (2009), in the same Christie’s day sale mentioned above, is estimated to sell for between £150,000 and £250,000. Meanwhile, at Victoria Miro’s stand at Art Basel in June, a large 2015 pastel drawing on paper sold at the VIP opening for £300,000.

Auction prices for her smaller drawings, etchings and prints are “much more in line with primary market prices”, Lindo says. Cristea Roberts Gallery deals in the artist’s prints and showed 16 works from the 2009 series, Curved Planks, at Art Basel, priced at €7,000 each.

For now, works by Rego remain unusually accessible for someone of her prominence. If not ready to commit to a purchase, interested parties can enrol in the art rental scheme Gertrude, started by the founders of London’s The Sunday Painter gallery, where three works on paper by Rego are currently available for short-term lease for £20 per month (and can be purchased for a total price of around £3,000).

Political power

Rego’s narrative images have ranged from slightly tinged to completely saturated with political undertones. That many of the issues that have long informed her biting commentary—migration, abortion, gender inequality—are top news items today has helped a new generation of viewers find her work. But can the polarising nature of politics put off potential buyers?

“Rego has always been known and appreciated for the social commentary she presents in her work,” says Touzin. Yet that doesn’t necessarily mean that commentary on her work has always kept pace. In the 1960s, when she was first exhibiting, and even through the 1980s and 1990s, “art dealer, critics, curators—they were mostly men,” Lindo says. “They would take from her work what they could understand and often leave what was more difficult for them to talk about.” That perception is now changing, Lindo adds.

Collectors and pitfalls

Touzin says that Rego has long been “celebrated as a national hero” in her native Portugal and has had consistent visibility in British institutions for decades, yielding a “loyal and serious collector base” in both countries. In addition to her long institutional exhibition history, Touzin notes that Rego’s representation by Marlborough gallery for two decades, before joining Miro and Cristea Roberts in 2020, has provided ample provenance and scholarship for her works.

The current market value for Rego’s work has certainly been set by UK collectors to date, Lindo says. “For a while figurative work was out of fashion, and to a certain extent she was overshadowed by her husband’s work. I think there are a lot of collectors who have had her on their radar for a long time but maybe haven’t added her work to their collection yet.”

That base is now widening—and prices will undoubtedly rise too. “We have seen a slew of new collectors acquiring works by Rego, from the very highest price point and down,” Carey-Williams says, adding that they are increasingly coming from the US and Asia. As Rego’s already acclaimed reputation grows internationally, Carey-Williams believes it is “inevitable” that prices will increase, “just as demand will”.

• Read Marina Warner's obituary of Paula Rego here