By lavishly funding the arts, the Medici signalled an end to the "dark ages" and kickstarted Italy's cultural rebirth. Florence, where successive generations of the family acquired monarchic levels of authority, became the European capital of the arts in the process. The Medici commissioned works from the likes of Donatello, Michelangelo, Da Vinci and Botticelli, spending over 663,000 florins on charity, building and taxes between 1434 and 1471 (for a sense of scale, consider that at the height of the family’s power Cosimo de Medici had amassed a total wealth of 123,000 florins). Today, Florence's museums, squares and churches burst with the products of the city's Renaissance flourishing. Our top ten guide shows you where to start.

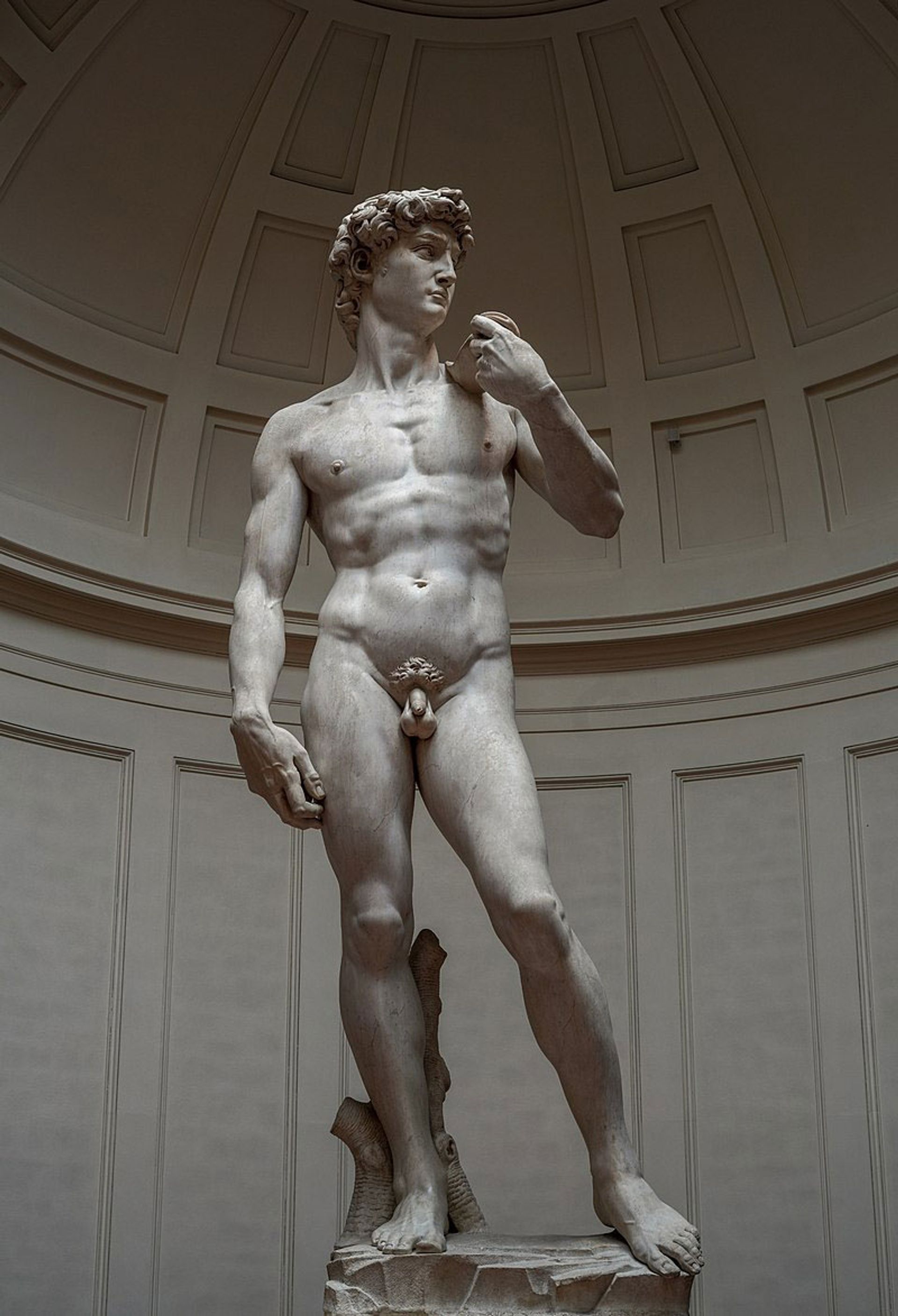

Michelangelo’s David (1501-04), Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze, Via Ricasoli

This towering masterpiece depicts David before his battle with the giant, Goliath. It was originally meant to be suspended in the niches of Florence Cathedral’s tribunes, 80 metres from the ground. But raising the six-tonne statue of the Old Testament figure was deemed too complicated, so the figure was placed in the square outside the Palazzo Vecchio instead. It was moved into the Galleria dell’Accademia in 1873 (a copy stands in the square today). Carved from gleaming white marble, the figure’s curved torso, with its sloped shoulders and angled hips, exudes beauty and strength.

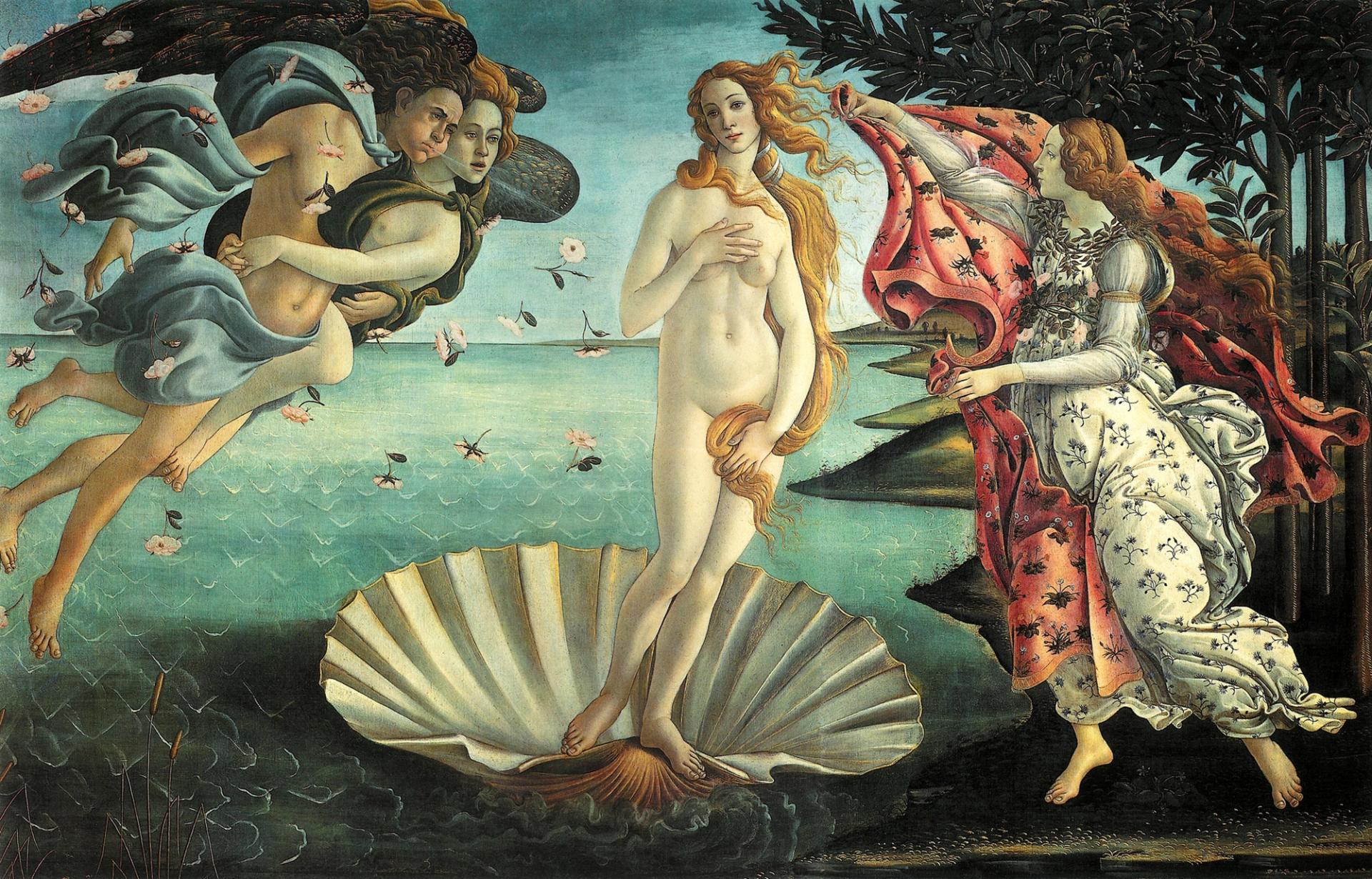

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (around 1482), Uffizi Galleries, Piazzale degli Uffizi

One of the most recognisable paintings in Western art, Botticelli’s masterwork shows Venus being born from seafoam, as Zephyrus—the Greek god of the west wind, here clutching the nymph Chloris—blows her towards Cytherea on a pearly white shell. The Hora of Spring, draped in floral, richly coloured robes, scatters flowers that swirl in Zephyrus’s vortex. Botticelli’s green and blue hues and undulating sea are so evocative you can almost smell a briny breeze. The work is thought to have been commissioned by a member of the Medici family. Today, it exerts a magnetic pull on Uffizi visitors.

Botticelli’s Primavera (around 1480), Uffizi Galleries, Piazzale degli Uffizi

Botticelli’s Primavera paved the way to a new conception of Western art for pleasure rather than religious moralising. More Pagan than Christian in origin, the work—commissioned by Pierfrancesco de’ Medici—is believed to represent blooming fertility. Cupid soars through a shadowy grove studded with ripe oranges. The undergrowth teems with nearly 200 varieties of flower (130 of them are specifically identifiable). A luminous Venus is accompanied by Zephyrus and Chloris, shown both as a nymph and a goddess scattering flowers. Three graces dance alongside Mercury, who is dressed in red and holding a sword.

Vasari’s The Last Judgement (1572–79), dome of Florence Cathedral, Piazza del Duomo

The iconic roof of Florence Cathedral remains the largest brick dome ever built. Cosimo de’ Medici had the interior frescoed by Giorgio Vasari, his court painter, and projected his image as a generous patron of Christian art in the process. A clear inspiration for this dizzyingly detailed work is Michelangelo’s own version of the scene on the roof of the Sistine Chapel. In the five concentric rings, Christ and Madonna together with angels occupy the upper areas, while the lower portions are dominated by representations of the horrors of the underworld.

Courtesy of the Museo Nazionale del Bargello

Donatello’s David (1440s), Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Via del Proconsolo

Donatello’s daringly erotic David is commonly described as the first Renaissance nude. It was originally commissioned for Florence Cathedral but never placed there. David is shown completely naked, save for his helmet and boots, as he poses with his foot on Goliath’s severed head. A delicately effeminate David runs a sandalled foot through Goliath’s beard curls, as a wing on Goliath’s helmet works its way up the hero’s leg. Donatello was in his early 20s when he created this work. Whether it is a comment on Florentine homosexual values at the time or the artist’s allusion to his own sexuality is up to the viewer.

Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise (1425-52), Baptistery, Piazza del Duomo

Michelangelo referred to them as the “Gates of Paradise” and the name has stuck. Lorenzo Ghiberti’s ten spectacular sculptural bronze and gold panels depict scenes from the Old Testament. They adorned the East Gate of the Baptistery for 500 years and survived various perils during that time, after being placed in storage in the 1940s to protect them from Allied bombs or being washed away in a flood of biblical proportions in 1966. Fluctuations in humidity were creating tiny craters and blisters on the panels’ gold surface, so the original pieces were moved into the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in 1990. They remain in the museum, while replica panels adorn the Baptistery’s doors.

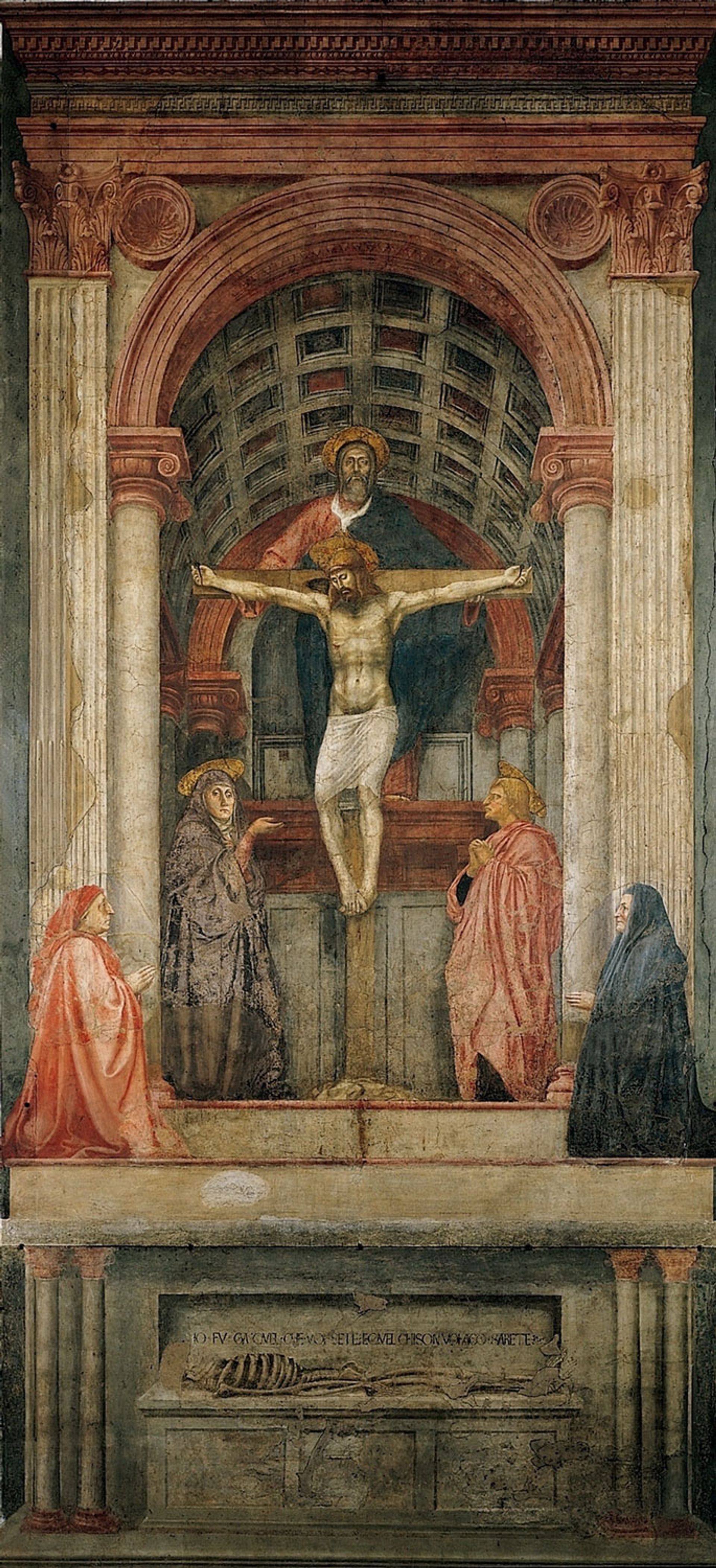

Masaccio’s Holy Trinity (1425-27), Basilica di Santa Maria Novella, Piazza Santa Maria Novella

Masaccio decisively altered the course of Western art, not least by applying the architectural lessons of Filippo Brunelleschi—who had revived the Ancient Greeks and Romans’ rules of perspective—to art. The Holy Trinityis a fine example of one-point linear perspective, in which objects appear to recede into the distance as they narrow towards a single vanishing point. In an allegorical journey from death to salvation, the viewers’ eyes are led from the skeleton at the bottom to depictions of the church’s donors, the Virgin Mary and Saint John, and, finally, Christ with God at the top.

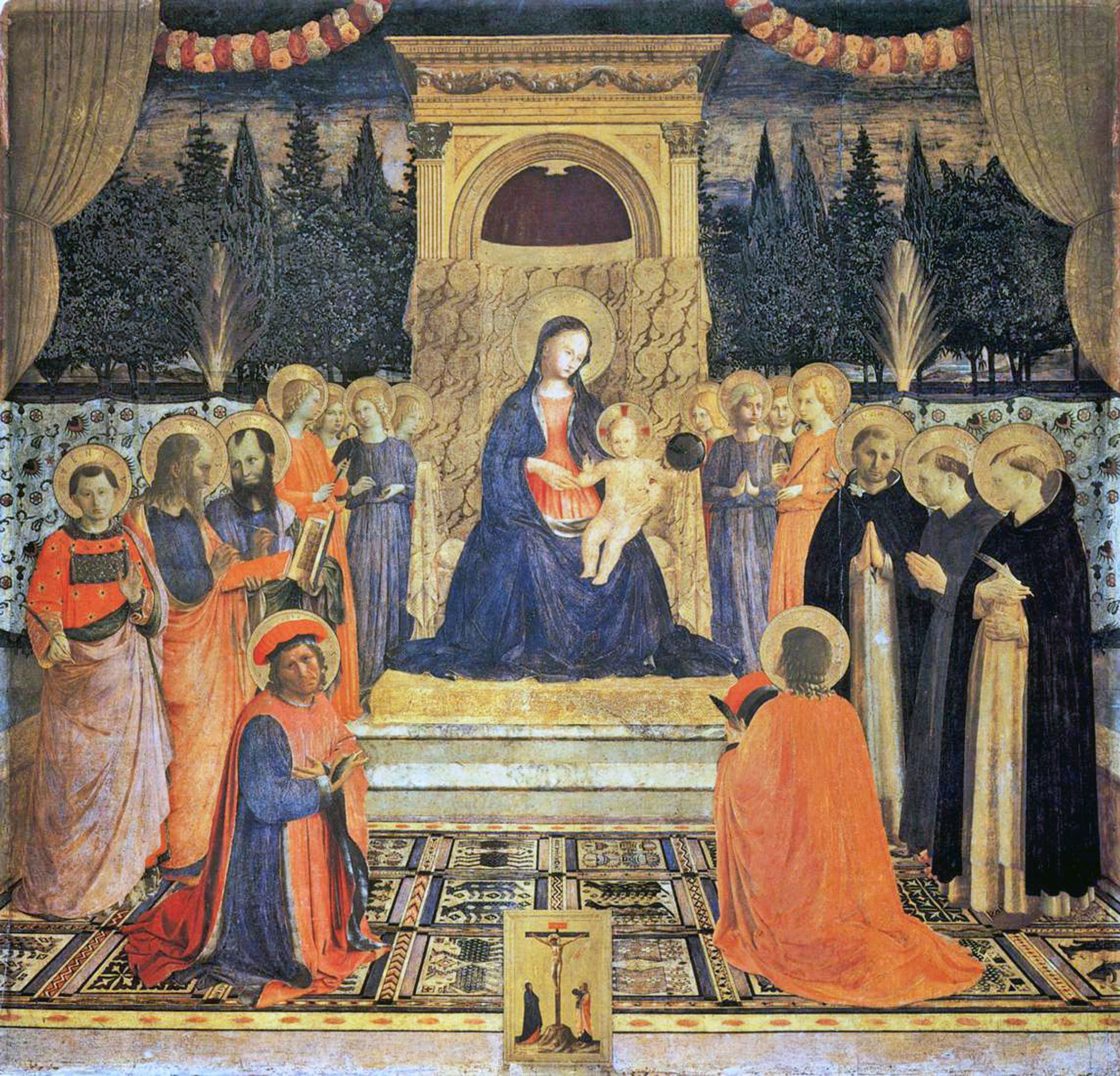

Fra Angelico’s frescoes, Museo di San Marco, Piazza San Marco

Tourists heading to the Uffizi or Florence Cathedral often bypass Fra Angelico's treasure trove of frescoes in the church of San Marco. Cosimo de’ Medici entrusted the complex to the Dominicans after rebuilding it in 1437. Fra Angelico became one of the order’s most devout monks, alongside Girolamo Savonarola. Together with Giotto and Donatello, Fra Angelico ushered in the High Renaissance by abandoning the rigid expressionlessness of Gothic art and imbuing characters with radiant depth. His San Marco frescoes—which, according to Vasari, the artist always painted after praying—include lunette depictions of saints in the cloisters, and the epic Crucifixion with Saints.

© WGA

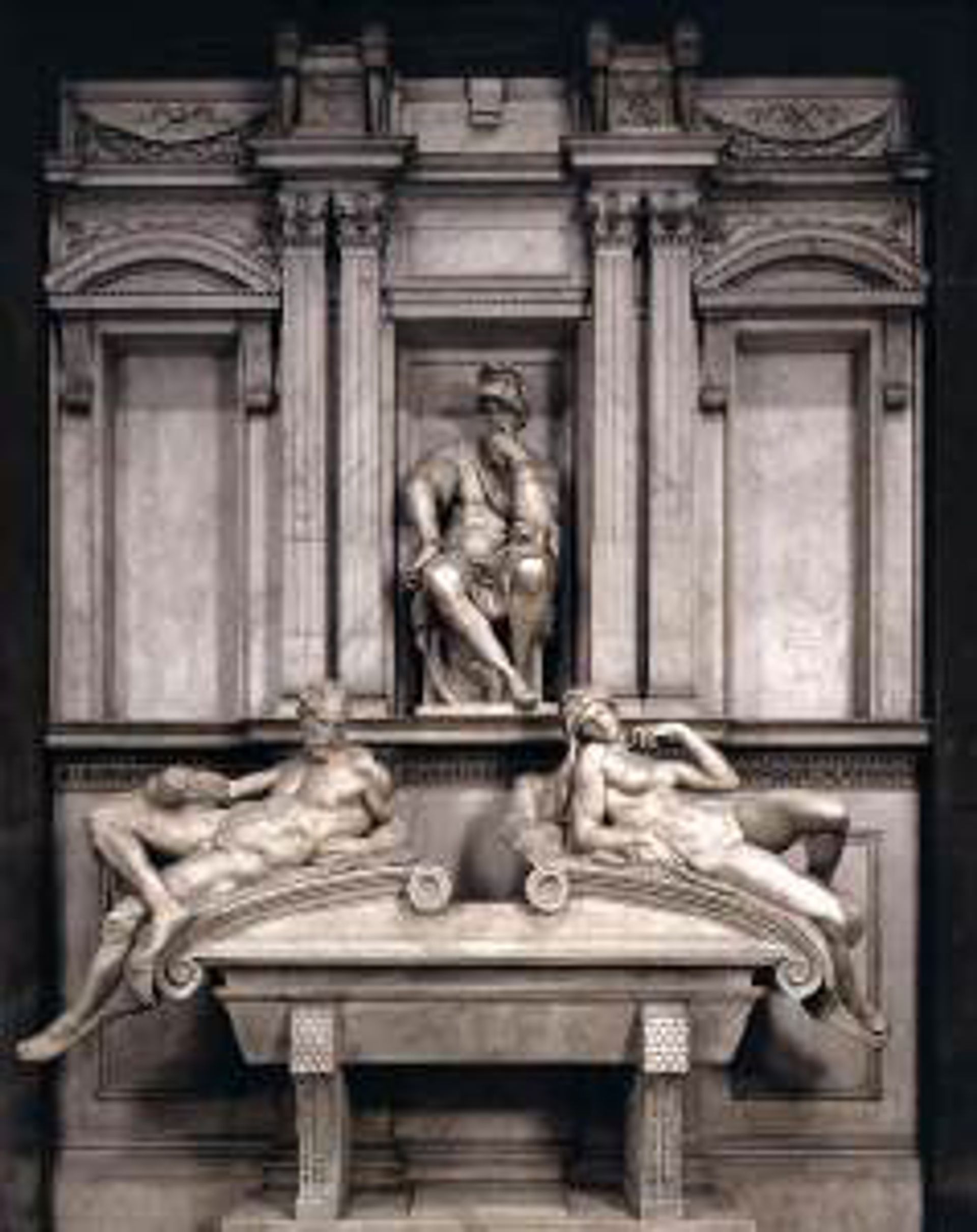

Michelangelo’s tombs (1519-24), Sagrestia Nuova, Basilica di San Lorenzo, Piazza di San Lorenzo

Pope Leo X, originally Giovanni de’ Medici, had the Sagrestia Nuova built following the deaths of the family's two younger heirs, Lorenzo di Piero and Giuliano di Lorenzo. Michelangelo was enlisted to design everything from the windows, cornices, columns and two tombs, providing one of the fullest existing examples of his architectural vision. The statues representing the buried Medicis are placed in upper niches above each tomb. These are dwarfed with enormous reclining figures—representing day and night on one tomb, and dawn and dusk on the other—which, together, allude to the passing of time that leads to death. An eight-year renovation of the works was completed in March.

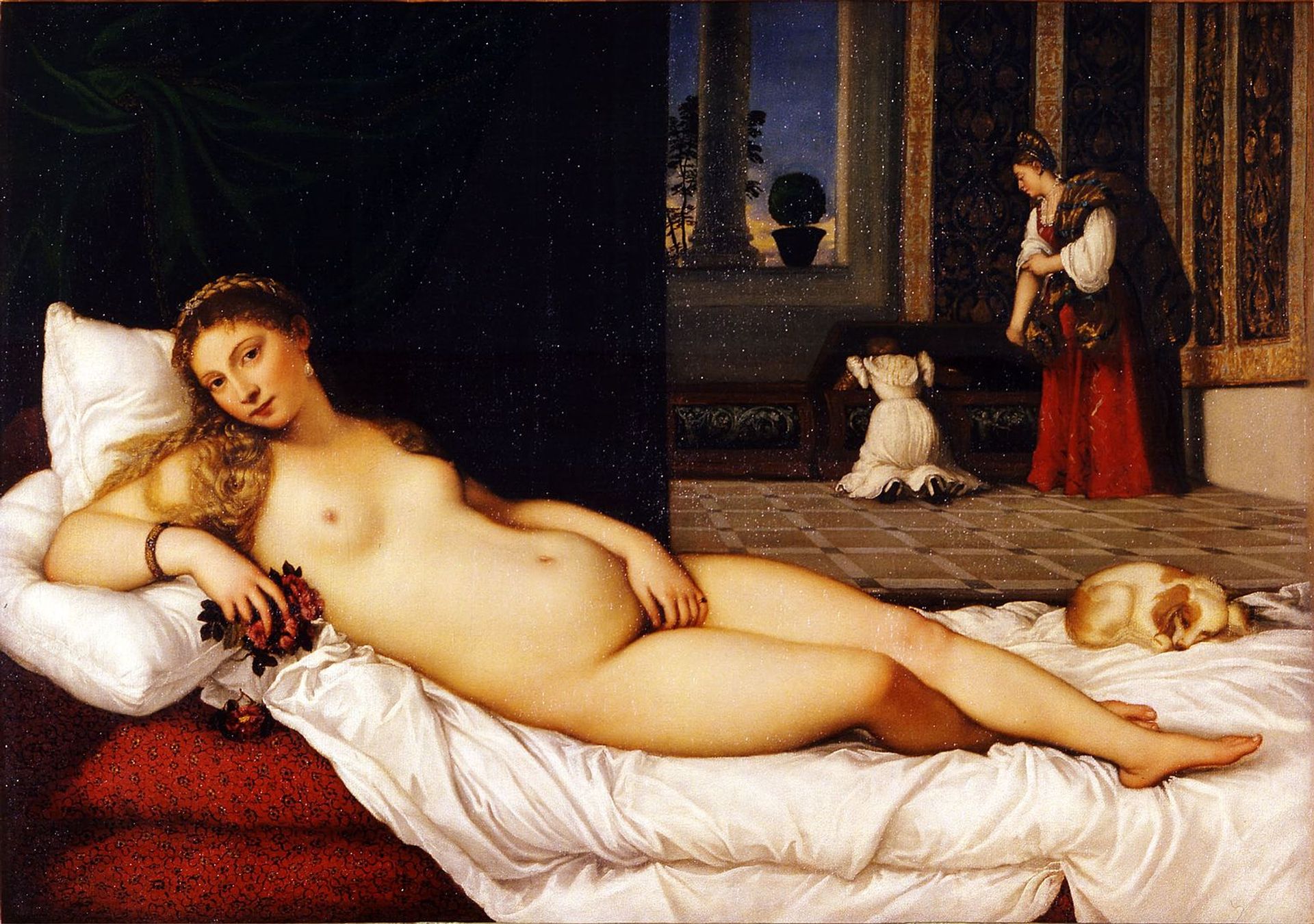

Titian’s Venus of Urbino (around 1538), Uffizi Galleries

Commissioned by Guidobaldo II Della Rovere, the Duke of Urbino, this work was apparently intended to provide moral instruction to Giulia Varano, the Duke’s young bride. A homage to Giorgione’s La Venere dormiente (around 1510), Titian’s painting is layered with symbolism. The reclining Venus’s evident eroticism reminds us of the bride’s obligations to her husband. The dog at her feet symbolises faithfulness. The child seen behind signifies hopes for fertility. Unlike Giorgione, Titian (unusually) opted for a domestic setting, hammering home the work’s function as a stimulant for private reflection.