Nearly four years late and costing around £19bn, London’s east-west Crossrail project is at last (almost completely) open for business. Now known as the Elizabeth Line in honour of HM’s platinum jubilee, it is a major feat of engineering, boring down through the centre of London to link Heathrow Airport and Reading in Berkshire in the west to Abbey Wood in south-east London and Shenfield in Essex to the east, adding 10 brand-new stations and a fittingly regal purple presence on the new tube map.

Yet these grand statistics tend to overshadow the fact that the Elizabeth Line has also been accompanied by the most ambitious commissioning of permanent public works of art in London for at least a century. And this is not just art as a bolt-on or final embellishment: in each case, the work was developed by a leading contemporary artist alongside the design of the building and in close collaboration with Crossrail engineers and architects. In many cases, they also directly reference a station’s location within the city, as well as the communities that it will be serving.

Chantal Joffe will make 2m-tall portraits for Whitechapel station.

Chantal Joffe has lived in east London for many years and her 2m-tall portraits made from laser-cut aluminium for the platform walls at the Elizabeth Line’s Whitechapel station are inspired by her Sunday wanderings among the cosmopolitan crowds thronging the streets and markets around the station—a neighbourhood that has been home to many of London’s migrant communities for centuries.

“Whitechapel is a vivid, beautiful diverse area that’s full of people and with an incredible atmosphere,” Joffe says. She adds that she "wants the art in the station to link the under ground with the above ground and the sense of Whitechapel as a bustling inner city place. It’s really important that you feel that aliveness very strongly.”

Newham Wall Artwork at Custom House. Photo: Benedict Johnson

Sonia Boyce, who currently represents Britain at the Venice Biennale, also grew up in London’s East End and her series of colour-printed panels that stretch along the trackside in Newham feature more than 170 illustrated stories that she collected from local people of all ages and backgrounds.

Newham Trackside Wall by Sonia Boyce for Crossrail. Photo: Benedict Johnson

Newham Trackside Wall is Boyce’s first public work of art, stretching for nearly 2km alongside the Elizabeth Line’s east London tracks as they snake through the capital’s former docklands. It is one of the longest artworks in the UK and is a testament to Boyce’s view of the docks as “the gateway to Britain’s relationship with the rest of the world.” Many of the tales it tells bear witness to the myriad communities and their goods who have lived among and passed through the docklands during its often chequered history.

Spencer Finch's A Cloud Index (2022) at Paddington station. Courtesy of Crossrail

The giant artificial cloudscape that Spencer Finch has created for the 2,300 sq. m glass roof of Paddington station brings together more than 30 different cloud types that would never naturally appear together at the same time, replicated in frit paint made from crushed glass. These range from the chunkiest of cumulonimbus to the lightest of wispy cirrus and interact with the real clouds outside.

This cloudy canopy is partially inspired by John Constable’s Sky series, visual documentations of his “skying” expeditions on Hampstead Heath, not too far down the tube from Paddington (with a change at King’s Cross). Finch says that his work “exists both as an artificial cloudscape and as a homage to the British obsession with categorising and systematising the most fugitive of natural phenomena".

Spectre by Simon Periton is embedded into the exterior glazing of the Elizabeth line station at the eastern ticket hall in Farringdon Station. Courtesy of Crossrail

In Farringdon station, Simon Periton evokes the area’s history as the centre of the UK jewellery trade, having digitally printed enormous images of gems onto the backlit glass panels of the interior walls along the western ticket hall.

Michael Rovner's Transitions (2019)

There’s more passenger movement in Israeli artist Michal Rovner’s work for Canary Wharf. Here, a large video screen features repeated rows of silhouetted figures, which move along different levels of horizontal and slanted lines in a composition inspired by the dramatic architecture of the station. “I’ve always been fascinated by human movement in time and space and the continuous flow of people passing from one place to another,” she says. “I hope that my work in this place, seen by millions of people will remind them that the time that they take for granted, going from one place to another, and the space between, is actually very meaningful.”

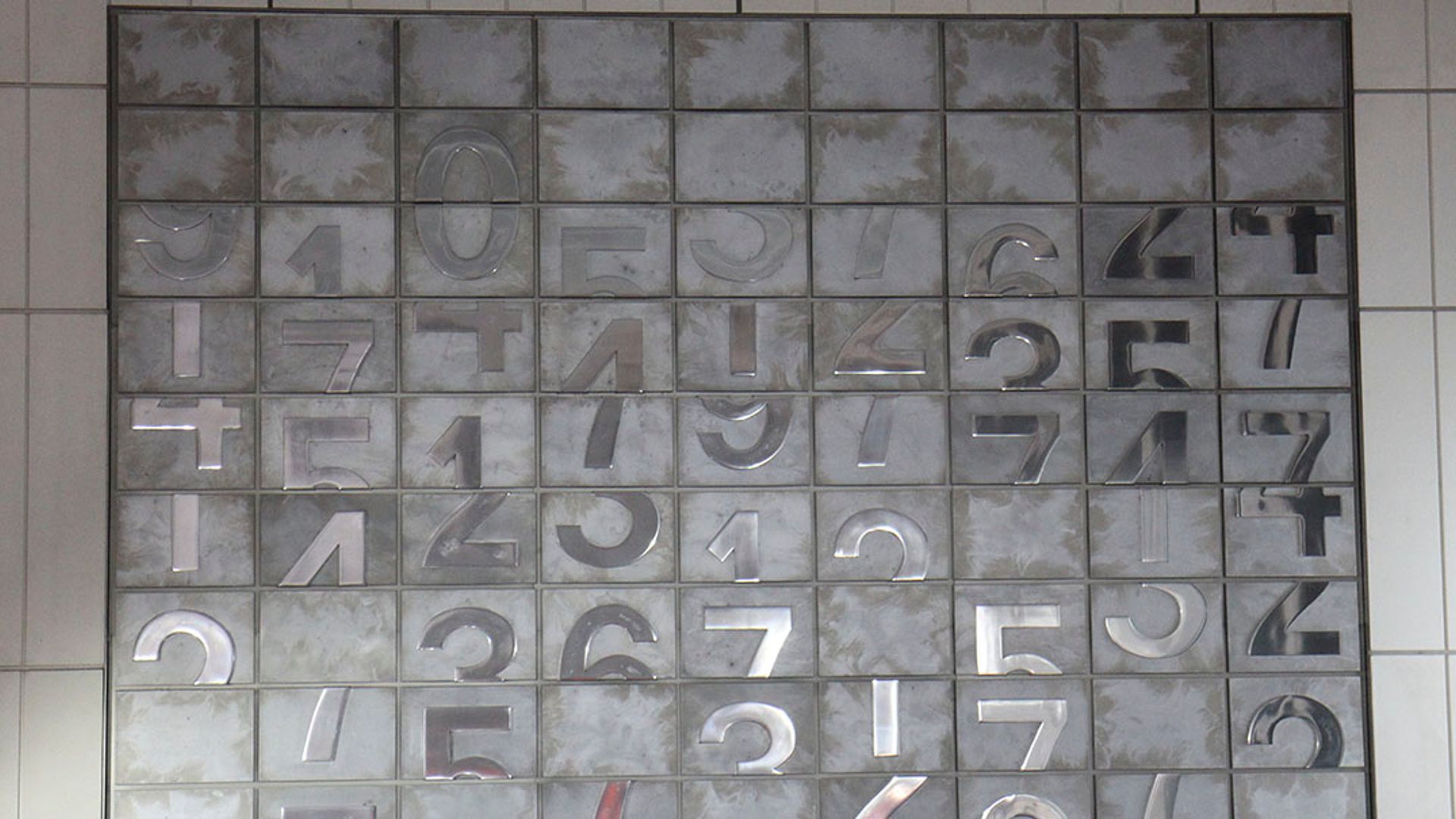

Darren Almond’s abstract field of fragmented numbers at Bond Street station. Courtesy of Crossrail

Bond Street station is not due to open until later this year but, when it does, Darren Almond’s abstract field of fragmented numbers cast in a grid of 144 aluminium panels over the main escalators also taps into the traveller experience of hectic schedules and daily routines.

Passengers descending down to the Elizabeth Line will also encounter two more of Almond’s giant metal signs declaring Reflect from Your Shadow and From Under the Glacier, which offer more philosophical musings on departures, arrivals and deep geological time. As he puts it: “We are in those strata and literally coming up from under the glacier. What could be more dramatic than to be reminded that your physical presence here, at this very point, is only made possible by passing through geological time itself?”

Douglas Gordon evokes a more personal history for Tottenham Court Road’s Dean Street ticket hall with a new film work that draws on his memories of wandering round the red light district of Soho in the late 1980s when as he first came down to London from his native Glasgow to study at the Slade School of Art. “I used to walk around that neighbourhood as a wee Scotsman only looking at things outside – because I was too nervous to go in,” he says. Gordon’s film is still being tweaked at the time of writing, but will soon be beamed out into the surrounding streets.

Installing Richard Wright's intricate, geometric gold-leaf pattern onto Tottenham Court Road station. Courtesy of Crossrail

The other work for Tottenham Court Road is a geometric wall drawing by Richard Wright in gold leaf. One of Wright’s few permanent pieces it stretches across the concrete ceiling above the escalators, offering a subtly-shifting experience for ascending and descending travellers with the artist hoping that “it will provide a moment of preoccupation or delay, and that perhaps out of your peripheral vision you might engage with this space”.

While all these works are already in situ, Liverpool Street Station is still waiting on two exterior works. Conrad Shawcross’s sinuous bronze sculpture, which gives physical expression to a musical chord “falling into silence” will be installed later this year in the public space by the station’s Moorgate entrance.

Digital rendering of Yayoi Kusama's planned sculpture for Liverpool Street station. Courtesy of Crossrail

And Yayoi Kusama’s linked steel spheres will descend in a swooping fashion outside the station’s eastern ticket hall in 2023. “London is a massive metropolis with people of all cultures moving constantly,” Kusama says. “The spheres symbolise unique personalities while the supporting curvilinear lines allow us to imagine an underpinning social structure.”

Even if a few additions still need to be made, given Crossrail’s bumpy ride, the fact that all these complex, carefully considered public works have—or will—come to fruition can give Londoners a welcome moment of pride. All aboard!