For more than a decade, Frida Kahlo wrote letters to Leo Eloesser, a thoracic surgeon who became her trusted medical adviser until her death in 1954. In some letters, she takes an endearing tone. In others, she asks his forgiveness for her delay in writing or sending his painting, or asks for his advice on her quest for socialist revolution or critical healthcare decisions. The letters paint a heart-wrenching portrait of a complex woman whose image has been flattened, co-opted and commercialised. The incredible struggles she faced are often overlooked, but fragments of her life left behind in letters and documents justify her position as one of the 20th century’s most significant cultural figures.

Kahlo Without Borders, an exhibition at the MSU Broad museum in East Lansing, Michigan (until 7 August), examines the minutiae that made up Kahlo’s life: the letters asking for money, apologising for delays with paintings or for her husband Diego Rivera’s bad behaviour, searching for answers regarding her deteriorating health or treatments for her constant pain. Across 15 clinical files, 90 framed letters sent over decades to doctors, friends and family, and a handful of original drawings, the exhibition honours the support system that helped lift Kahlo to her pedestal.

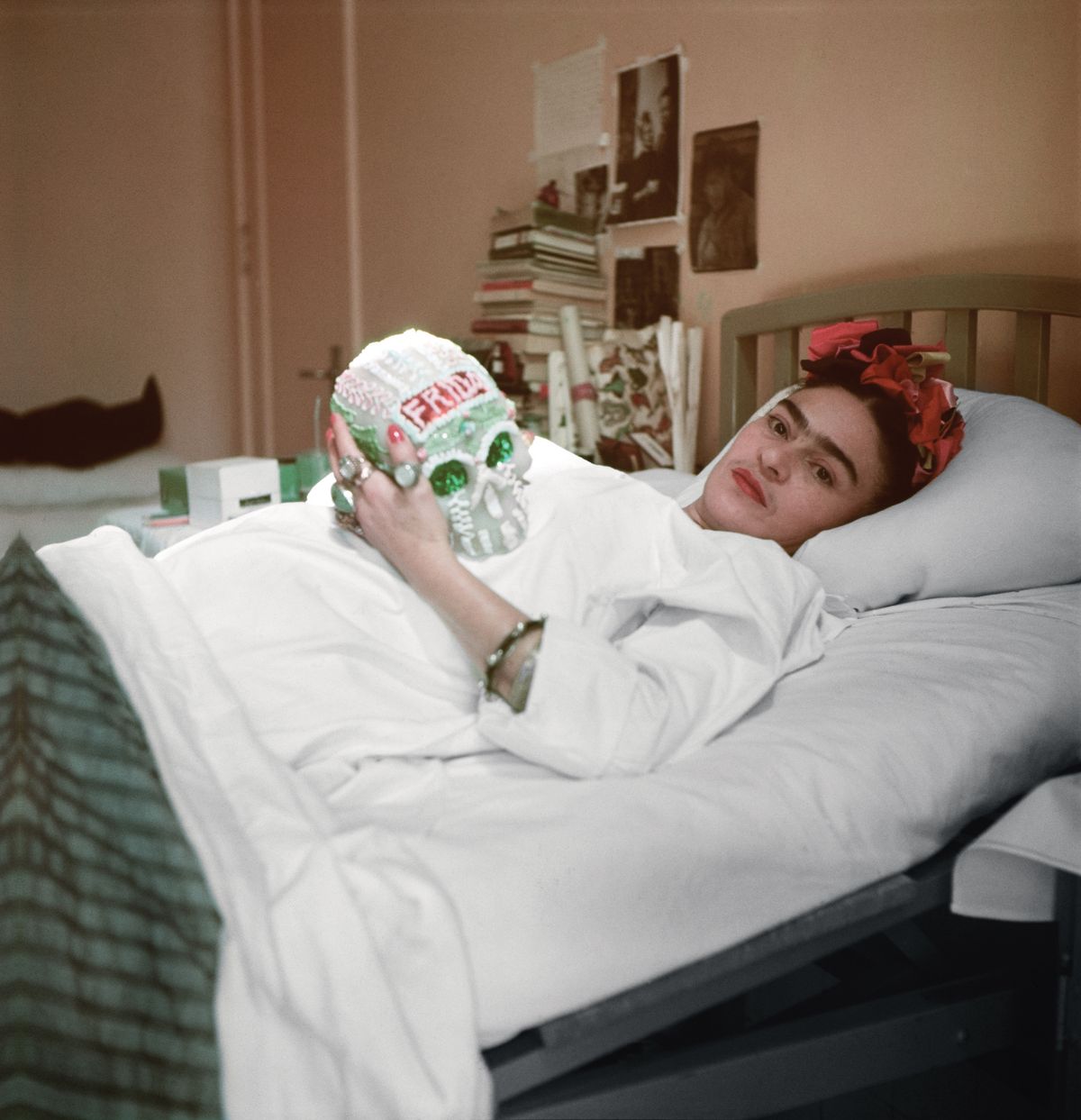

Kahlo in hospital in 1953. The artist was seriously injured in a bus accident when she was just 17 years old, leaving her in pain for the rest of her life Courtesy of Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive

Organised by the MSU Broad director Mónica Ramírez-Montagut, the exhibition was made possible by a stroke of luck for the artist’s grand-niece, Cristina Kahlo, who also co-curated the show. According to Ramírez-Montagut, Cristina Kahlo had spent more than four years trying to get her grand-aunt’s medical records from the American British Cowdray Hospital in Mexico City. “The records detail what she ate and drank in the morning, cardiograms of her surgeries, or post-op notes,” Ramírez-Montagut says.

Since Cristina Kahlo could only copy the records from the hospital, most are displayed as photographs against light boxes, lending the exhibition a sombre and sterile quality, a departure from the exoticism that typically swirls around the artist. Ramírez-Montagut and the artist’s grand-niece chose to portray Kahlo’s life as it was—an often rote journey between hospital and home, peppered with colour by her paintings and political assertions, and a precarious financial position that forced her to pay debts with artistic favours.

Bartering and bargaining

The medical records lend the exhibition its visual style, but the letters are the heart of its story. From those written to Eloesser to letters to her former paramour Nickolas Muray, her sisters and her friends, the missives reveal how Kahlo bargained with loved ones and herself to achieve her goals. In a letter to Muray in 1939, the year she divorced Diego Rivera (they remarried in 1940), Kahlo promised she “would never accept money from a man ever again”, determined instead to sell her paintings or barter them in exchange for small loans. In several letters to Eloesser and Hollywood star Dolores del Río, she negotiates allowances or payment for services by remitting paintings or news of upcoming exhibitions and awards.

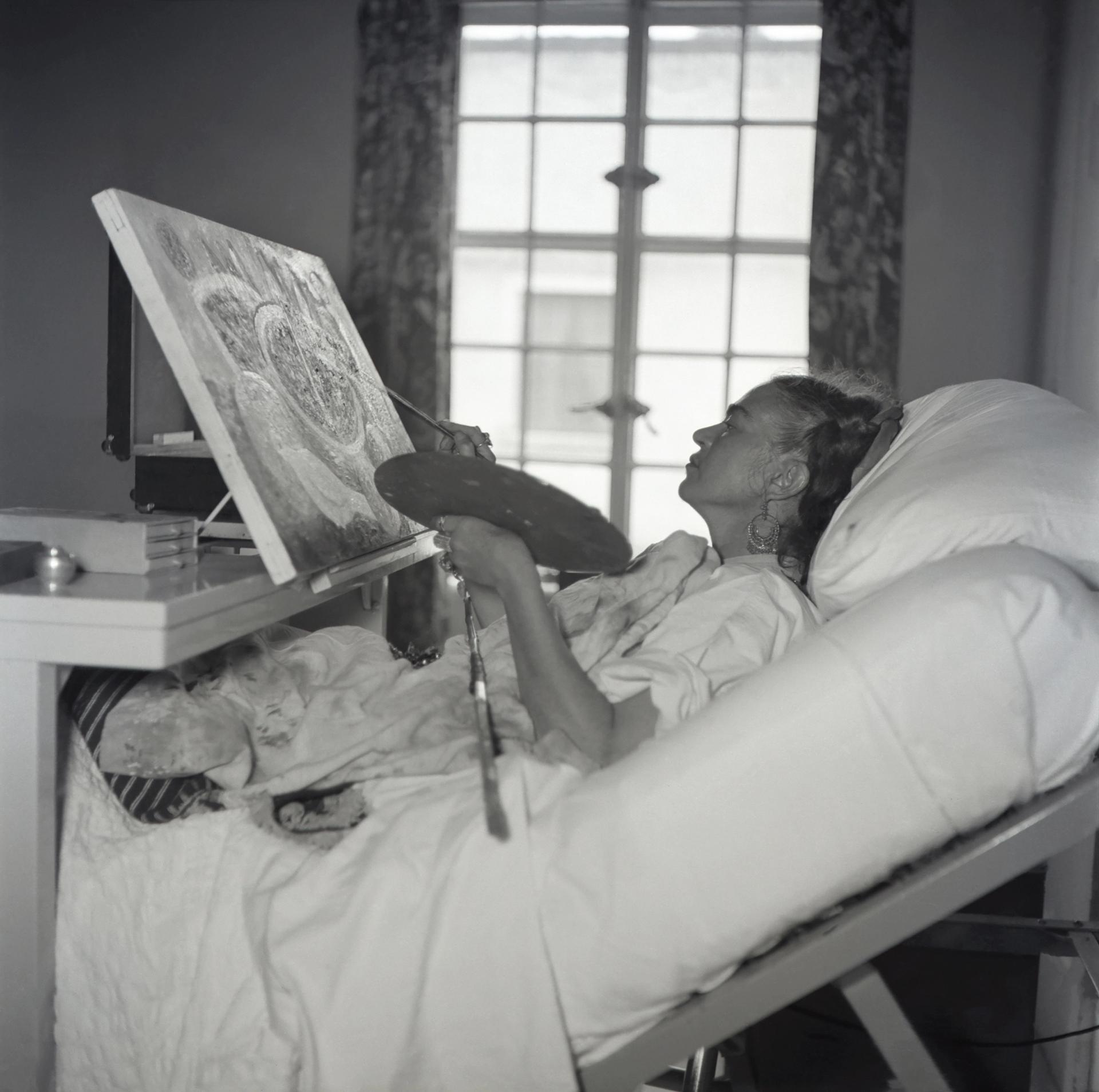

Frida Kahlo at the Hospital Inglés painting Long live life and Dr. Juan Farill in 1953 Courtesy of Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive

“While a small part of her life was very visual and became a spectacle, the bulk of her life had a tone more akin to what we’re presenting in the show,” Ramírez-Montagut says. “Asking for favours, paintings for the doctors, borrowing money, asking for her things to be sent to the hospital. It’s more than what we see in so many of her portraits, many of which she performed for.”

The materials show the intense restrictions of Kahlo’s life following the 1925 bus accident that nearly killed her. In two startling photos taken 20 years apart and shown side by side, Kahlo is pictured in bed, clutching and creating new works. That so much of her life was lived in this horizontal position as she navigated her injuries and her pain speaks directly to the exhibition’s premise, Ramírez-Montagut says.

Frida Kahlo at the American British Cowdray Hospital with puppets in 1953 Courtesy of Fundación Televisa Collection and Archive; photo: Juan Guzmán

I think it’s important that we challenge the narrative of ableism and [tendency to] paint Frida as a film character that’s almost perfectMónica Ramírez-Montagut, director, MSU Broad

“I think it’s important that we challenge the narrative of ableism and [tendency to] paint Frida as a film character that’s almost perfect,” she says. “She had a tremendous support system, and for all of us to acknowledge that community is important. In many of these objects, you can see that Frida’s doctors were concerned about her being in pain and not having any funds.”

With these newly available materials, the exhibition attempts to pinpoint Kahlo’s boundless resolve in tiny moments when she and her supporters overcame challenges. It shows that the type of greatness she attained is rarely achieved alone. “There’s not one single individual that accomplishes so much on their own,” Ramírez-Montagut says.